Foreword

MESSAGE FROM STEWART BECK, PRESIDENT AND CEO, APF CANADA

Canada has been fortunate to have strong trade and investment partners in the United States and Europe, and those relationships will evolve but endure. The growing significance of the Asia Pacific, however, along with the recent rise of protectionism among Canada’s traditional trade partners, means it is increasingly imperative that Canada look across the Pacific in order to secure its own long-term economic prosperity.

As the importance of the Asia Pacific to Canada’s economy grows, it is vital that we can both qualify and quantify our two-way investment relationship with the established and emerging economies of this region in order to better inform Canadian policy-making and public discourse.

The lack of complete and publicly available data on these foreign direct investments (FDI) may well be contributing to a lack of understanding of their true impact on the Canadian economy and on Canadian employment, which demonstrably benefits from new “greenfield” FDI investments from overseas partners in Asia. In APF Canada’s recent survey on Asian investment in Canada, for example, Canadians estimated that FDI from China made up 25 per cent of Canada’s total inward direct investment – while the actual figure is closer to 3 per cent. This type of misperception, our polling further showed, is directly tied to negative opinions on FDI – opinions exacerbated by a lack of information and corresponding trust.

The objective of our three-year Investment Monitor project is to support business, government, and civil society by better aggregating, cataloguing, and bringing utility and transparency to the body of data pertaining to the two-way flow of FDI between Canada and the Asia Pacific.

It is our hope, and that of our project partner, The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary, that the Investment Monitor will in its first year shine a spotlight on Asia Pacific investment in Canada to demonstrate how an infusion of financial and human capital, as well as technological and management expertise from Asia, will benefit Canadian businesses at home and Canadian firms looking to do business in the dynamic markets of the Asia Pacific.

Stewart Beck, President and CEO, Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada

LETTER FROM EVA BUSZA, VICE-PRESIDENT OF RESEARCH AND PROGRAMS, APF CANADA

In recent times, both policy-makers and the public have engaged in a lively discussion about foreign investment coming into Canada. They have posed a number of key questions. How much foreign investment do we want to attract into Canada? Who do we want investing and in what sectors of our economy? How should we monitor and regulate foreign investment? With Asian economic ascendance and increasing Asian interest in investing in Canada, the dialogue today is focusing specifically on our investment relationship with Asia.

However, whether it is strategies for attracting foreign direct investment or policies for regulating it, a common starting point is the need for robust information on the nature, distribution, and source of investment flows. To date, correct, clear, and coherent data has been surprisingly elusive. While Statistics Canada, Canada’s national statistical agency, has sought to provide information on investment flows, regulatory constraints have prevented it from being able to give the public a complete view of Canada’s investment ties, especially with the Asia Pacific. Some private companies have done their best to patch together a picture, but their findings are not freely available to the public.

In an effort to fill this gap, the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) — whose mandate calls for the collection of “information and ideas relating to Canada and the Asia Pacific region and disseminating such information and ideas within Canada and the Asia Pacific region” — is undertaking a project to develop a web portal that provides the public with data on the nature of the Asia Pacific’s direct investment into Canada. Our hope is that our website can provide a basic resource that can be further developed over time.

This report presents the findings of our first year of research. It aggregates raw data from APF Canada’s archive on investment deals acquired from commercial databases, media reports, industry associations, investment promotion agencies, and other sources. Over the next two years, we will concentrate on ensuring our findings are up-to-date, and on filling emergent gaps in the data.

While we do not claim that our data collection is comprehensive, we hope that both the database we have developed and the resulting report will improve the coverage of investment data in Canada. This in turn should serve to advance policy development on FDI, support businesses in decision-making, catalyze academic research on investment, and help provide foundational facts for an informed public debate on foreign investment.

We would like to thank all of our sponsors for their guidance and support — the Government of British Columbia, AdvantageBC, the Bank of Canada, Export Development Canada, and The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary. Without them, APF Canada would not have been able to undertake this important project. I would also like to thank our team at the Foundation, which made this project a reality – especially our Program Manager, Justin Elavathil, and our Project Specialist, Pauline Stern.

Dr. Eva Busza, Vice President, Research and Programs, Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada

Executive Summary

As a region, the Asia Pacific is fast becoming one of the most influential contributors to global outward investment in the world. [1] Canada is one of the destinations that has seen a rise in this investment from Asia. Although official statistics show that Asia Pacific investment in Canada is growing in importance, little detailed information is publicly available on the volume, scale, or scope of foreign investment in Canada. It is because of this that the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) partnered with The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary in the creation of the APF Canada Investment Monitor, a new data set that provides a better understanding of the investment ties between the Asia Pacific and Canada. In addition to the partnership of The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary, further support was provided by the Government of British Columbia, AdvantageBC, the Bank of Canada, and Export Development Canada to develop the APF Canada Investment Monitor, a resource to better understand the investment ties between the Asia Pacific and Canada. [2]

Data from the APF Canada Investment Monitor shows that Asia Pacific investment into Canada has grown in spurts from 2003 to 2016. The main sources of this investment are China, Japan, and Australia, representing nearly 70 per cent of the investment flows from the region.

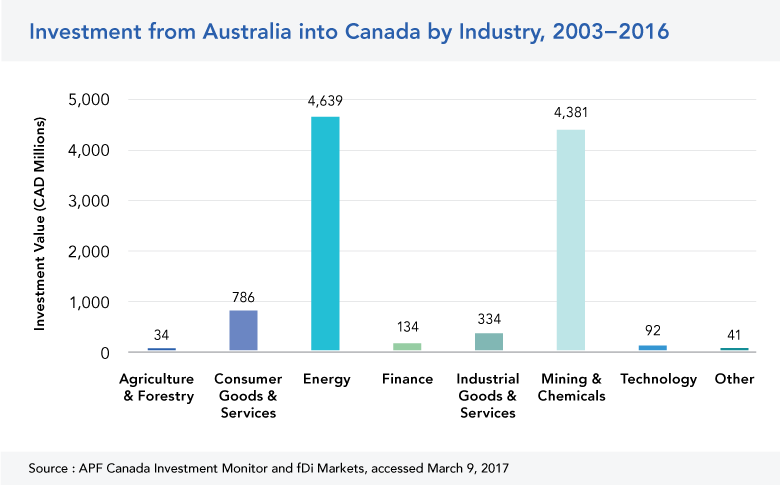

Although Japan led the first wave of investment (2003-2007) from the Asia Pacific into Canada, its investment peaked in the period of 2008 to 2012, and after 2013, was on the decline. Most of Japanese investment from 2003 to 2016 was in consumer goods and services, especially tied to strengthening Canada’s automotive production. China then led the second wave of investment (2008-2012) as a result of China’s “Go Global” policy, which made Canada a large recipient of Chinese outbound investment in natural resources. Australian investment into Canada, on the other hand, has been consistent over the years, with the exception of a sharp decline in the past two years. A considerable amount of investment from Australia has gone into Canada’s natural resource industries — particularly energy and mining, in which Australian multinationals are among the world’s leaders.

The main industries that attracted investment were tied with Canada’s natural resources, such as agriculture and forestry, energy, and mining and chemicals. Even though the value was considerably larger for these natural resource-based industries, the number of deals in non-natural resource-based industries, such as consumer goods and services, finance, industrial goods and services, technology, and others, accounted for more than 60 per cent of the total number of deals completed between 2003 and 2016.

At the provincial level, Asia Pacific investment in Canada was focused primarily on the four provinces with the largest economies over this period — British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec. Each of these provinces attracted different types of investment. British Columbia and Alberta attracted more energy-related investments; Ontario, automobiles and retail; and Quebec, mining. Canada’s Prairies, Atlantic Provinces, and Territories have seen little growth over time, yet these regions have potential, especially for small and medium-sized investments.

Although Canada is seen as a safe and welcoming economy in which to invest, it continues to lag behind some of its competitors. Many of its competitors have increased the number of investment agreements they have with Asia Pacific economies, making them more attractive to Asian investors.

APF Canada and The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary hope that the APF Canada Investment Monitor will shine a spotlight on Asia Pacific investment in Canada and encourage a greater understanding of how this investment contributes to Canada’s current and future economic prosperity.

The views and opinions expressed in this report are solely those of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, and not those of our project partners and sponsors.

ENDNOTES

[1] Asia Pacific includes economies from East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Oceania.

[2] This release is part of a multiphase project. Data on outward FDI from Canada to Asia will become available in subsequent years.

Introduction

THE FUTURE IS THE ASIA PACIFIC

The centre of the global economy is shifting from the U.S. and Europe to the Asia Pacific. According to data from the International Monetary Fund, in 2001 the Asia Pacific made up 29 per cent of global gross domestic product (GDP) in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP), while in 2021 this figure is projected to grow to 45 per cent, or nearly half of the world’s economy.

The main drivers of this shift can be attributed to the emergence of future economic giants, China and India, Asia Pacific’s established economies such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Taiwan, and also smaller, but growing economies in Southeast Asia. Commensurate with this growth has been the expansion of Canada’s trade and investment relations with these economies.

Although the U.S. will remain Canada’s most important trade and investment partner for the foreseeable future, Asia Pacific economies have been supplanting Canada’s other traditional partners in importance over the past decade. Also, with a new and more protectionist U.S. administration taking power in 2017, Canada must look beyond North America and across the Pacific in order to secure its own future economic prosperity.

When it comes to building economic relations with international partners, the flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) (see definition in Box 1) into Canada is one of the more important forms of capital coming into the country. Unlike the inflow of capital from portfolio investments (see definition in Box 1) and trade, direct investment involves a high degree of commitment in terms of the investor’s time and expertise. [1] Foreign enterprises or residents who make a direct investment in Canada also become invested in Canada’s economic success. This makes FDI important not only economically for Canada, but also as a bridge for creating people-to-people ties between economies.

IS CANADA'S LACK OF INVESTMENT ARCHITECTURE PREVENTING IT FROM ATTRACTING INVESTMENT?

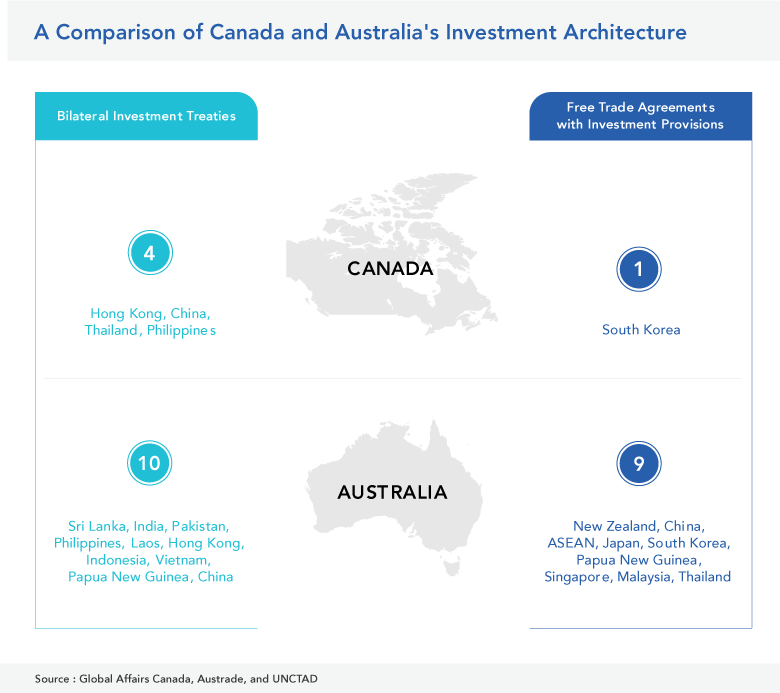

Unlike trade, which benefits significantly from establishing free trade agreements (FTAs), there is no specific mechanism that fosters FDI. The closest are bilateral investment treaties (BITs), also known in Canada as foreign investment promotion and protection agreements (FIPAs), which can enhance investment flows by creating a welcoming environment and facilitating relations conducive to business.

Currently, Canada has four FIPAs in force with Asia Pacific economies (China, Hong Kong, Philippines, and Thailand); another one is signed (Mongolia), and two are under negotiation (India and Pakistan). These agreements, combined with the investment chapter in its FTA with South Korea, give Canada eight agreements with Asia Pacific economies that contain investment provisions.

In comparison, Australia, a country that recognized early on the importance of building economic ties with the Asia Pacific and benefits from closer access to many Asia Pacific economies, has 10 investment agreements and 8 FTAs in force with Asia Pacific partners. The investment chapters within its bilateral and multilateral FTAs expands the scope of Australia’s agreements that include investment provisions with Asia Pacific economies to 21. Australia’s ability to forge these agreements may in part be why the Asia Pacific features more prominently in its investment relations, making up 25 per cent of its total inward investment stock, or the total value of investment assets in the country, in 2015. In Canada, according to official statistics, this figure was only 11 per cent in the same year.

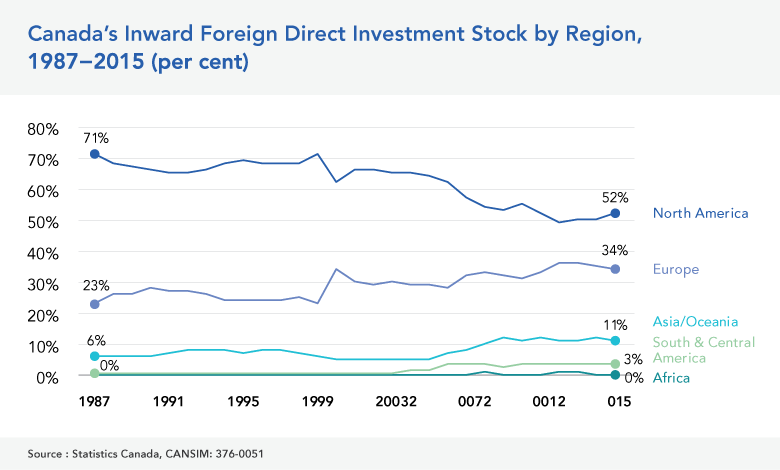

THE LIMITS OF OFFICIAL STATISTICS

Despite the importance of FDI to the Canadian economy, little information is publicly available about the volume (the number of deals), scale (the size of investment value), or scope (distribution across regions and industries) of foreign investment in Canada. Statistics Canada, the official repository of data on foreign investment in Canada, shows that Canada’s inward FDI stock from the Asia Pacific has been increasing over time. Yet it is from 2005 that the region’s share of investment stock in Canada has shown considerable growth, more than doubling from approximately 5 per cent in 2005 to nearly 11 per cent in 2015.

The few data tables that are publicly available from Statistics Canada, however, provide an incomplete view of Canada’s investment ties, especially with the Asia Pacific. Official statistics on investment in and out of Canada are derived through international standard balance of payment calculations, a top-down approach that acquires data mainly via banking system reports and direct surveys. The limitations of this type of approach are: 1) the sources and destinations of investments exclude subnational-level categorizations; 2) due to privacy concerns, much of the investment data from specific Asia Pacific economies is protected and therefore not available; 3) the source and destination of some investments are difficult to account for due to the transfer of investment through third-party economies; 4) an industry breakdown of investment from each Asia Pacific economy is not available; and 5) there is a substantial lag in publication of up-to-date data.

The lack of publicly available data on the volume, scale, and scope of Asia Pacific investment in Canada, may in part have led to a lack of understanding of its importance to and impact on the Canadian economy.

For example, in a recent survey conducted by APF Canada on Asian investment in Canada, Canadians estimated that FDI from China made up 25 per cent of Canada’s total inward direct investment, while the actual figure at the time was closer to 3 per cent.

This misperception of the size of Chinese investment in Canada is also tied to negative opinions on this investment, as Canadians who significantly overestimated the value of Chinese investment in Canada were also more likely to say Canada has allowed “too much” investment into the country from the socialist economy. [2]

THE VALUE OF ANOTHER APPROACH

Given the limitations in official statistics, it is clear that more data is needed in order to shed light on the nature of the Asia Pacific’s direct investment in Canada. Improving the coverage of investment data in Canada can lead to improved policy development on FDI, support businesses in decision-making, catalyze academic research on investment, and help provide facts for an informed public debate on foreign investment.

The Investment Monitor uses a bottom-up approach that aggregates raw data from APF Canada’s archive on investment deals — investment contracts or arrangements that finance the creation or expansion of a business — acquired from commercial databases, media reports, industry associations, investment promotion agencies, and other sources. The transactions are aggregated into FDI flows, or the value of new cross-border investments in a particular year. The benefits of this approach are that it addresses the limitations of official statistics by 1) tracking investments to the subnational level, including provincially and municipally by both value and number of deals; 2) revealing investment values for economies that were previously unavailable; 3) ascertaining the ultimate investors and beneficiaries of investments; and 4) providing a more detailed and intuitive breakdown on investments by commonly used definitions of industries and sectors for each investing economy.

Unfortunately, no data set on foreign direct investment can provide the complete picture on Canada’s investment ties with the Asia Pacific. In terms of the Investment Monitor, its limitations are in its historic tracking of data, only available from 2003 to present, and its comprehensiveness, as it only includes information on FDI transactions covered in public media sources.

While the differences between the methodologies of top-down and bottom-up approaches make it difficult to compare official statistics with Investment Monitor data, the goal of the Investment Monitor is not to replace Statistics Canada investment data, but to complement it in order to provide a better understanding of the Asia Pacific’s investment relations with Canada.

For a more thorough description of the differences between bottom-up and top-down approaches and the APF Canada Investment Monitor’s methodology, please see the methodology and glossary page.

BOX 1. CROSS-BORDER INVESTMENT AND FDI

Cross-border investments can be separated into two major groups: 1) foreign portfolio investment (FPI) and 2) foreign direct investment (FDI).

1) FPI is considered a temporary investment by a resident or enterprise of one economy into a financial asset of another economy. This investment involves a non-controlling stake in an enterprise in the form of equity and/or debt securities as well as loans. For example, a resident of Australia buying a small share of stock on the TSX would be considered FPI.

2) FDI is defined as a long-term or lasting-interest investment by a resident or enterprise of one economy into a tangible asset of another country. This type of investment is deemed to be “long-term” or of “lasting interest” if it is either a greenfield investment or an acquisition of at least 10 per cent equity or voting shares of an enterprise. This 10 per cent threshold is considered a controlling interest in an enterprise and is what primarily distinguishes FDI from portfolio investment, since it also usually coincides with a transfer of management, technology, and organizational skills along with capital. For example, a Japanese firm buying a 20 per cent stake in a pulp mill would be considered FDI.

Source: APF Canada Investment Monitor

ENDNOTES

[1] Rhodium Group. Two-way street: 25 years of US-China direct investment.

[2] Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2016 national opinion poll: Canadian views on Asia.

The National Picture

ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENTS IN CANADA ARE GROWING IN VOLUME AND SCALE

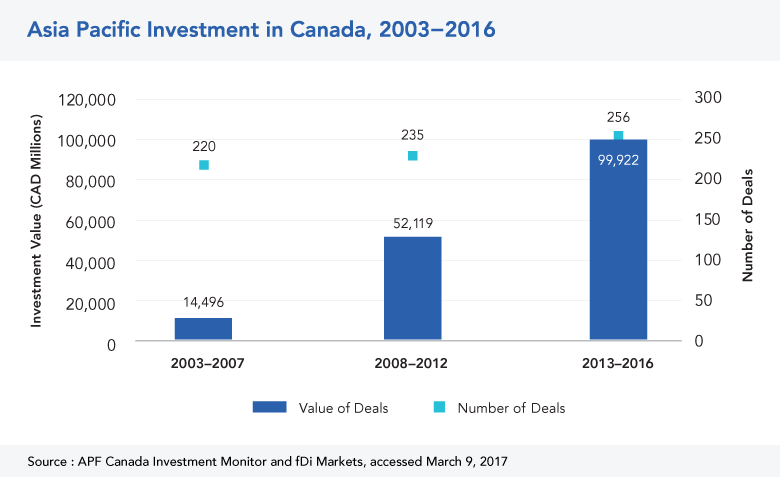

The APF Canada Investment Monitor data shows that Asia Pacific investment grew substantially in volume and scale from 2003 to 2016. However, due to the intermittent nature of investment flows into Canada, which sometimes makes for drastic differences in investment values each year, it is difficult to find trends from year to year.

When a historical analysis is required, this report will group investment into three time periods: 1) the embryonic period (2003-2007); 2) the rebalancing period (2008-2012); and 3) the rapid growth period (2013-2016). Further rationale for these groupings is to separate investments during the global financial crisis and its aftermath (2008-2012) and, in the case of China, to break up the exponential increase of Chinese investment in Canada following the introduction of China’s “Go Global” policy (see the Asia Pacific Investment Strategies section for a further explanation). When a historical analysis is not required, the whole data set is used.

ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENT VALUE REMAINS HEAVILY TIED WITH CANADA'S NATURAL RESOURCES, BUT DIVERSITY EXISTS

Whereas Statistics Canada uses the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) to classify investments in different industries, the APF Canada Investment Monitor uses a modified version of the Industrial Classification Benchmark (ICB) system created by FTSE International and modified by APF Canada. The modified ICB provides a more intuitive way of classifying investments, especially in new and burgeoning industries that are not accurately accounted for in NAICS.

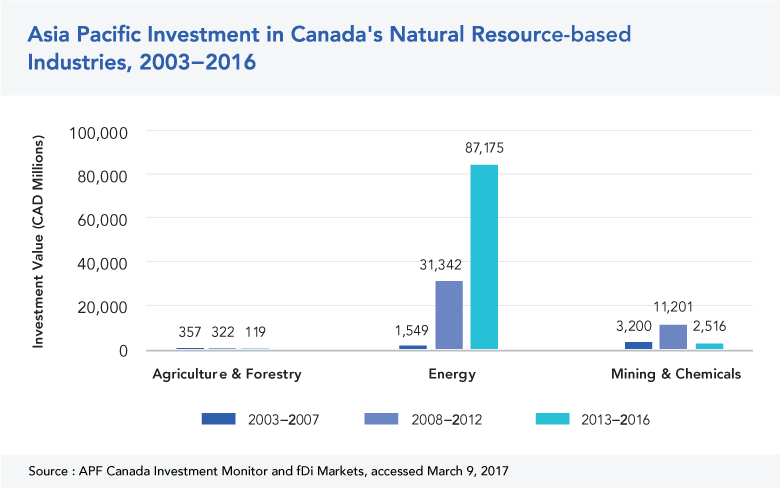

Investment Monitor data shows that in terms of investment value, Asia Pacific investment is mostly connected with Canada’s natural resource-based industries (agriculture and forestry, energy, and mining and chemicals), constituting 82 per cent of the total value of investment from 2003 to 2016. However, in terms of the number of deals, these investments only make up 37 per cent of the total. The majority of this investment value was in the energy industry during 2013 to 2016, and is the main cause for the rapid growth during this period.

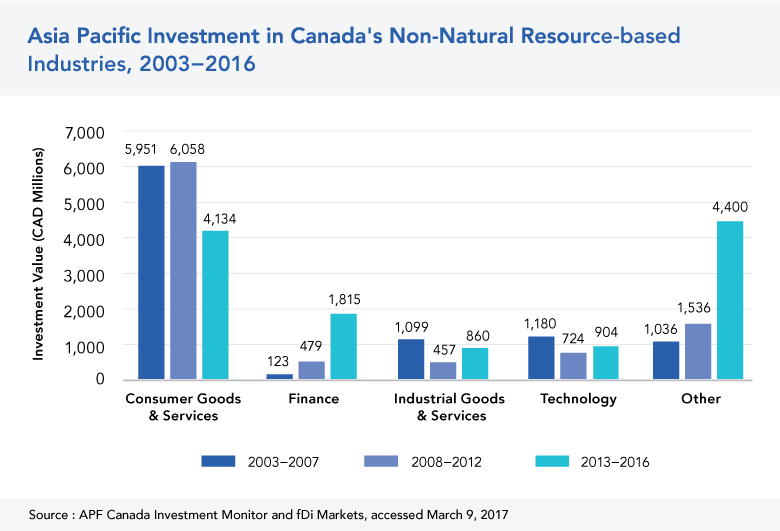

Whereas Asia Pacific investment in Canada’s non-natural resource-based industries (consumer goods and services, finance, industrial goods and services, technology, and other) comprised only 18 per cent of investment value from 2003 to 2016, it made up 63 per cent of the total number of deals.

With respect to investment value and number of deals, consumer goods and services is the industry that attracted the most investment among non-natural resource-based industries, with 10 per cent of the total investment value and 24 per cent of the total deals from 2003 to 2016.

During the rebalancing period (2008-2012), an interesting phenomenon occurred. Although there was no real change in the investment value, the number of investment deals in non-natural resource-based industries dropped significantly from the previous period (2003-2007), especially in consumer goods and services and industrial goods and services. This coincided with a large increase in the number of deals in natural resource-based industries.

Table 1. Number of Asia Pacific investment deals in Canada, 2003-2016

|

Time period |

Natural resource-based industry deals |

Non-natural resource-based industry deals |

Total |

|

2003-2007 |

54 |

166 |

220 |

|

2008-2012 |

118 |

117 |

235 |

|

2013-2016 |

90 |

166 |

256 |

It is difficult to ascertain why this shift occurred, but it could be an effect of the financial crisis and the change in investment patterns during a time of economic uncertainty. Nonetheless, in the rapid growth period (2013-2016), the number of deals in both natural resource-based industries and non-natural resource-based industries have readjusted to pre-financial crisis levels.

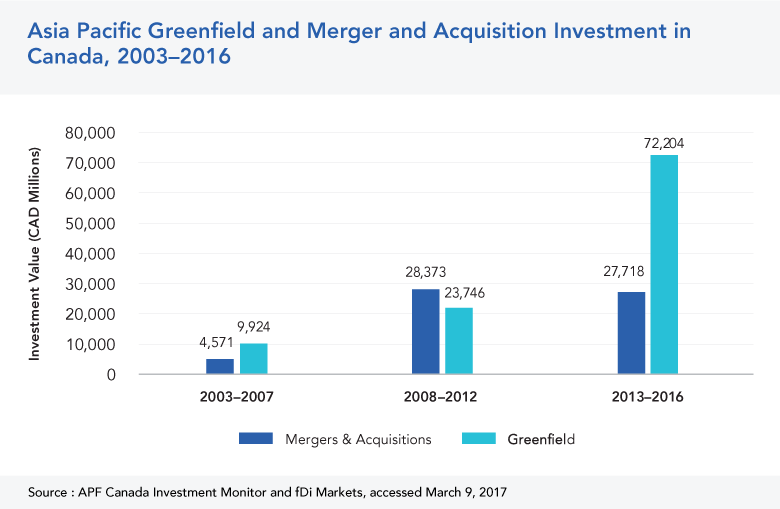

WHEN IT COMES TO TYPE OF INVESTMENTS, NEW VENTURES ARE THE MOST COMMON

Asia Pacific investment was mainly focused in greenfield investments from 2003 to 2016, with 64 per cent of the value and 67 per cent of the number of deals. During the rebalancing period (2008-2012), mergers and acquisitions (M&A) were the preferred type of investment in terms of both value and number of deals. Once again, it is difficult to determine if this result is tied to the economic uncertainty during the financial crisis with companies attempting to mitigate risk in foreign investment by linking capital to existing facilities rather than starting new ventures.

BOX 2. INVESTMENT TYPES

Foreign direct investments can be generally broken down into two categories:1) greenfield, and 2) mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

1) A greenfield investment is an investment from a company in a new venture outside its own economy that results in the construction of a new facility (distribution hubs, production factories, offices, and/or living quarters) or an expansion upon such an initial investment. [1] The advantage of greenfield investments is the ability to create a new facility that can be designed to meet current and future needs at reduced initial maintenance costs, while the disadvantages are the possible long startup times, high initial capital investment, and difficulty in securing a location for new facilities and hiring new staff.

2) An M&A investment is an investment in an existing company through acquiring a significant number of shares. [2] The advantage of M&A investments is the ability to take over partial or total ownership of an existing facility immediately with reduced initial capital investment and little need to hire new staff, whereas the disadvantages lie in possible long-term high maintenance costs, inefficiency in current production methods, and suboptimal location.

Source: APF Canada Investment Monitor

Barring any new financial crisis or economic downturn in Canada, greenfield investments should continue to comprise the majority of Asia Pacific investment in the country.

ARE CANADIANS' FEARS OF STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISE INVESTMENTS OVERBLOWN?

The Investment Monitor classifies a state-owned enterprise (SOE) as an enterprise in which a national or subnational government has a controlling interest in the company. This controlling interest can either be considered as being the single largest shareholder of a company or by having a voting power that equals 10 per cent or more. [3]

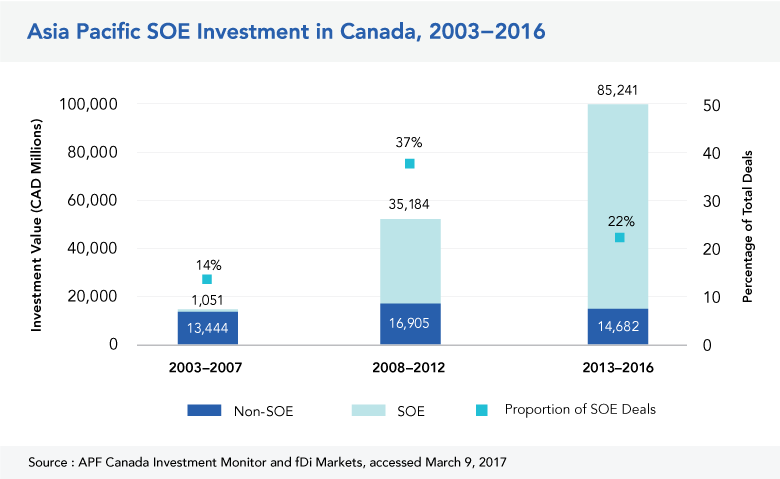

Although SOE investment only makes up a total of 24 per cent of the number of deals from 2003 to 2016, it constitutes 72 per cent of the total investment value. The reason behind this is that the bulk of SOE investment is concentrated in a few large deals in natural resource-based industries. Investments from SOEs in energy and mining and chemicals make up 70 per cent of the total investment value from the Asia Pacific in Canada, but only 15 per cent of the number of deals.

In the wake of large acquisitions by Asia Pacific SOEs China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and Petronas in Canada’s energy industry, negative public perception surrounding the role of foreign state-owned companies escalated. The sheer size of investments triggered a review of these investments by the Government of Canada that evaluated them in terms of the net benefit to the country’s economy. [4]

BOX 3. INVESTMENT VIGNETTE: PULLING THE WELCOME MAT OUT FROM UNDER SOEs' FEET

Investments from state-owned enterprises (SOEs) consistently elicit concerns over ownership and appropriation of national resources. In 2012, two headline-making deals by foreign SOEs brought these issues to the forefront in Canada and led to an amendment in the Investment Canada Act (ICA) and Canada’s policies towards inward FDI. China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC)’s $15-billion purchase of Calgary-based Nexen and Malaysian state-owned Petronas’ $5-billion purchase of Calgary-based Progress Energy signalled a turning point in Canada’s approach to foreign SOE investors.

In 2013, as a result of these two deals, the ICA was revised to include an expanded definition of SOEs. The definition of SOE in the Act was changed to include individuals acting under the direction of a foreign government as well as individuals or enterprises either directly or indirectly influenced by a foreign enterprise. In addition, whereas before investment from SOEs (and non-SOEs) above $330 million triggered a review, now the Act explicitly states any investment from an SOE, regardless of value, will trigger an automatic ICA review.

The flow of SOE investment has slowed considerably following the 2013 amendment made to the ICA. Although investments from SOEs in Canada did not halt, the changes to the ICA have signalled that SOEs are less welcome.

However, this perception could be changing with a new government in power. For example, a takeover bid by Hong Kong-based O-Net Communications of Montreal-based ITF Technologies, a leader in “fibre-laser” technology that was deemed “injurious to national security” by the prior Conservative government, is now undergoing a “fresh review” by the Liberal government. This could be a sign of a new approach toward SOE investment in Canada.

Source: APF Canada Investment Monitor

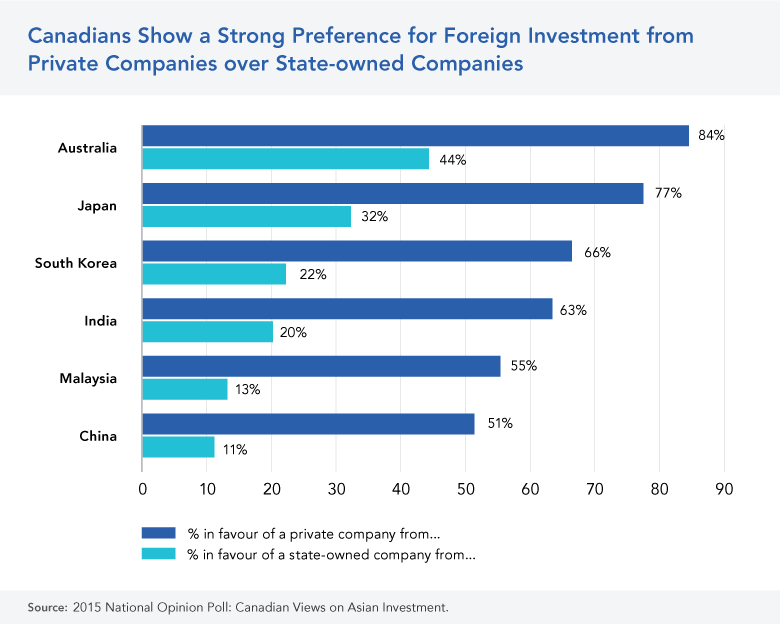

Canadians are generally wary of investments from state-owned enterprises. In APF Canada’s 2016 National Opinion Poll, survey results show that Canadians are more likely to favour private investment than SOE investment from Asia Pacific economies. It is clear that fears about foreign SOE investment overshadow the potential benefits these investments have for the Canadian economy.

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

- Investment from the Asia Pacific remains heavily focused on Canada’s natural resources sector; however, the last five years has seen a diversification of investment areas of interest.

- Greenfield is the preferred investment method for Asia Pacific-based companies.

- Investments by Asia Pacific-based state-owned enterprises are few in quantity but high in dollar value.

ENDNOTES

[1] Investopedia. Green field investment.

[2] Investopedia. Mergers and Acquisitions: Definition.

[3] This definition is similar to the one used by UNCTAD (2011).

[4] Beaulieu and Saunders. The impact of foreign investment restrictions on the stock returns of oil sands companies. School of Public Policy, University of Calgary Volume 7, Issue 16, June 2014.

The Provincial Picture

PROVINCES WITH LARGER ECONOMIES ATTRACT MORE ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENTS

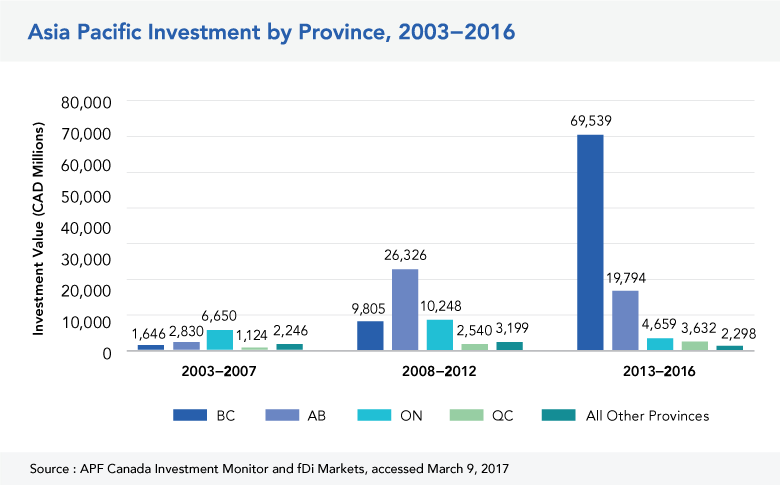

APF Canada Investment Monitor data shows that over the past 14 years, Asia Pacific investment in Canada has remained focused on the four provinces with the largest economies: British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec.

This focus is perhaps unsurprising as these four provinces have long been the primary entry points for international capital flow into Canada. However, while these provinces have remained the top four destinations, their ranking in this group has shifted in tandem with the increasing share of Asia Pacific capital originating from mainland China.

In the early 2000s, investment from the Asia Pacific into Canada was mainly a story of automotive manufacturing investment from Japan into Ontario. Later in the decade, however, a large increase in natural resource investment from China into Alberta shifted the story of Asia Pacific investment in Canada westward.

While the Prairies, Atlantic Canada, and the Territories still have yet to see their economies rise as a focus for Asia Pacific investment, pioneering small to medium-sized investments are paving the way for Asia Pacific companies to familiarize themselves with how to operate in Canada’s smaller provinces.

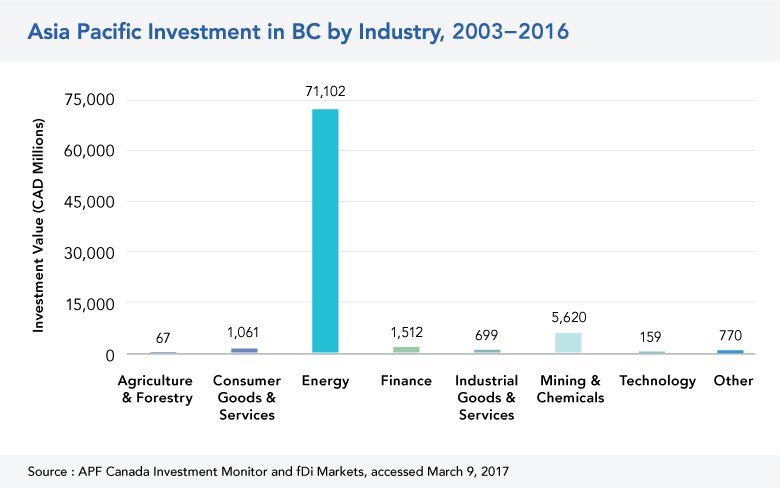

BRITISH COLUMBIA: PROVINCE-WIDE INTEREST IN ENERGY SECTOR, VANCOUVER-SPECIFIC INTEREST IN COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE AND TECHNOLOGY INDUSTRIES

British Columbia, as Canada’s gateway to Asia, has long been a focus of Asia Pacific investment in Canada. Of all Canadian provinces, B.C. has the largest trading relationship with Asia, the largest inflow of tourists from Asia, and the second-largest Asian visible minority population.

While the province has seen a continued growth of investment over the past 14 years, the focus of these investments has been divergent in Vancouver as compared to the rest of the province. Energy industry investments in the centre and north of the province still contribute the most to overall investment flows into the province. Two notable investments in particular, one by Malaysian state-owned Petronas and another by China state-owned Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd., have dwarfed the combined value of all other Asia Pacific investments in B.C. The scale of province-wide energy industry investments, however, obscures the story of Asia Pacific investment in Vancouver’s commercial real estate and technology industries. These two industries have in recent years experienced geographically concentrated booms in investment activity.

Vancouver’s commercial real estate industry, with a long history of investment from the Asia Pacific, has recently seen a rise in investment interest from China. In 2016 China-based Anbang Insurance Group Co. Ltd. purchased a controlling interest in Vancouver’s Bentall Centre for over $1 billion. Last year also saw the purchase of Oakridge Transit Centre lands for a reported $440 million by China-based Intergulf Development Group.

As well as a focus on commercial real estate, Vancouver has seen an inflow of investment to establish technology industry regional headquarters and development offices. More specifically, there has been a focus on video/mobile games development offices and movie production studio offices. One example of this is the relocation in 2015 of Japan-owned Sony Pictures Imageworks’ corporate offices from California to Vancouver, where it opened an office space that is reported to accommodate up to 700 employees. Currently, Japan-based companies are leading the way in the establishment of software/animation production offices; however, both China-based and Australia-based content developers have also opened offices in Vancouver within the past two years.

British Columbia’s investment profile will continue to focus significantly on the energy industry, but with an increasing interest in the technology industry and commercial real estate investments, an important shift to high-skill industries is occurring in the province’s most populous city of Vancouver.

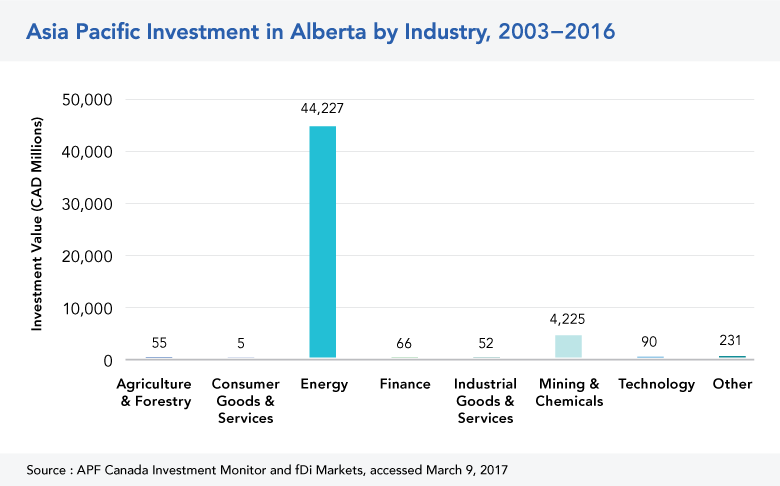

ALBERTA: DIMINISHED BUT CONTINUED INVESTMENT IN THE ENERGY INDUSTRY

Alberta has yet to recover from the decline in the price of oil. However, investments from the Asia Pacific into the energy sector continue to flow in, albeit on a smaller scale.

In the five years leading up to 2013, Alberta saw a fast rise in investment interest from the Asia Pacific, especially China. This interest reached a peak in 2013 with China-based CNOOC’s purchase of Nexen for $15 billion. Since then, the decline in investment can be attributed to a number of factors, namely, the decline in the price of oil, the uniqueness of such large-scale investments, and the rule changes made after the CNOOC deal to the Investment Canada Act.

While Asia Pacific-based investment in Alberta has yet to regain the magnitude of its peak years, investment is continuing in the energy sector. In 2016, China-based Geo-Jade Petroleum Corporation purchased Calgary-based Bankers Petroleum Ltd. for $575 million, and Sinoenergy Corporation Ltd. made a $500-million commitment to support operations of the Long Run Exploration Ltd. facility in Alberta.

As China and other Asia Pacific economies pause to reassess their investments in Canada’s oilsands, future investments from China’s SOEs may be expected, but on diminished scales. However, this could change depending on whether the Keystone pipeline and Trans Mountain pipeline expansions go forward. Both pipelines provide a greater incentive for investment in Alberta’s energy industry along with the increase in the price of oil.

BOX 4. INVESTMENT VIGNETTE: RECONCILING A NEW RELATIONSHIP WITH INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN CANADA AND ASIA PACIFIC BUSINESSES

In 2014, the Stoney Nakoda First Nation of Alberta signed a joint venture agreement with Hong Kong-based Huatong Petrochemical Holdings Ltd. to explore and develop oil and natural gas on approximately 49,000 hectares of land near Calgary. According to the agreement, Huatong would provide funding and Nakoda Oil & Gas Inc. would be the primary operator of the new joint venture company. The then chief of the Chiniki Nation, a member of the Stoney Nakoda Nation, was quoted as saying that he hoped the deal would bring the Stoney Nakoda Nation “one step closer to self-sufficiency.”

Foreign direct investment deals between Indigenous people in Canada and Asia Pacific-based businesses have the potential to allow Indigenous people in Canada to achieve their communities’ vision by providing financial backing and expert support in the development of their assets.

In 2013, Ambassador of Japan to Canada Norihiro Okuda, speaking at a First Nations LNG summit, said:

“[T]o develop natural gas in Canada, it is critical to develop mutual trust and understanding with First Nations. . . . [M]any Japanese companies have a great interest in doing business in Canada, but their plan is to first talk with First Nations to develop a mutual trust and understanding.”

Signalling that Japan sees First Nation groups as active partners, Japan, as well as other Asia Pacific economies are eager to learn more about developing a business relationship with First Nations in Canada. According to J.P. Gladu, president of the Canadian Council of Aboriginal Business, “We’ve seen a shift from First Nations being service contractors to now being primary producers. Countries like China are seeing an opportunity.”

In 2013, First Nations leaders accompanied British Columbia Premier Christy Clark on a trade mission to China, Korea, and Japan, where they focused on promoting LNG investment for their lands. Such trips and mutual learning between Indigenous people in Canada and Asia Pacific-based businesses help both groups gain the necessary cultural understanding to facilitate greater investment ties.

Investments such as the Stoney Nakoda Nation deal with Huatong Petrochemical deserve further analysis to better understand how to facilitate these mutually successful business relationships.

Source: APF Canada Investment Monitor

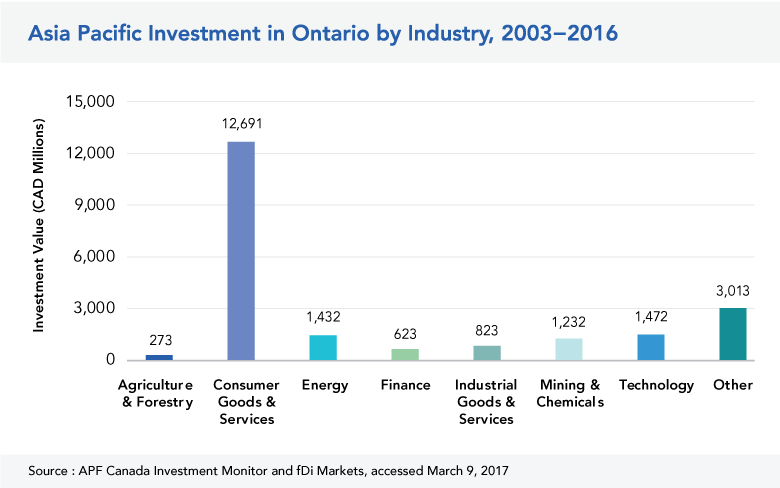

ONTARIO: AN INVESTMENT STORY DRIVEN BY AUTOMOBILES AND RETAIL

Over the past 14 years the manufacturing and consumption of consumer goods and services have played a central role in Ontario’s investment relationship with the Asia Pacific. From the early 2000s to the present, automotive manufacturing has been the primary vehicle for Asia Pacific investment in the province. More recently, the establishment of clothing and other retail flagships from Asia is playing an increasingly important role as Asia Pacific-based retailers seek to enter the North American market.

Ontario has had a long-running investment relationship with Japan. Specifically, Ontario has long hosted automotive manufacturing investments from Japan’s large business conglomerates, such as Mitsubishi and Toyota. This investment relationship endures into the present with these same business conglomerates making many repeated investments and site expansions in the province. Within the consumer goods and services sector, automobiles and parts for automobiles destined for use by consumers remained the largest sector of investment between 2003 and 2016.

Over the past five years, Ontario has seen an increase in focus on the province’s retail industry. Retailers long popular in Asia have begun expanding their presence in Canada by opening stores in Ontario. For example, Hong Kong-based jeweller Luk Fook opened the firm’s largest overseas store in Markham’s Markville Shopping Centre and Japan-based affordable-fashion retailer Uniqlo has opened two new stores in Toronto.

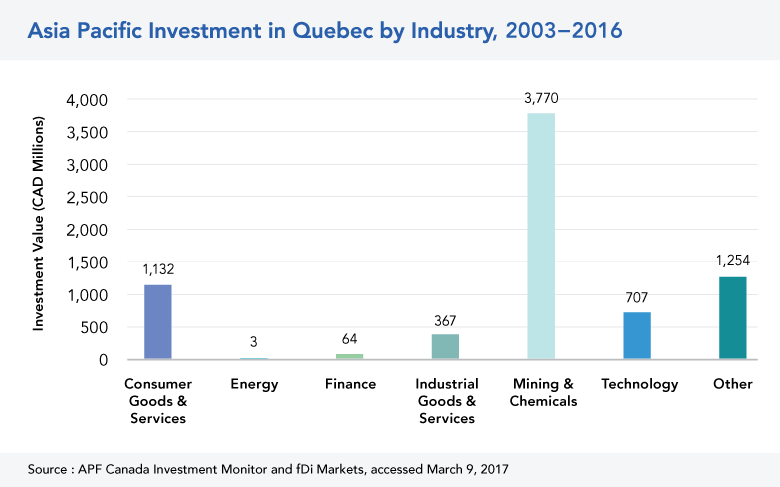

QUEBEC: MINING FOR BOTH NATURAL RESOURCES AND CULTURE

Between 2003 and 2016, direct investment in Quebec has been focused on the mining industry. More recently, Quebec has seen an interest in its cultural institutions.

Investment in Quebec’s mining industry remains strong with Chinese and South Korean nickel and iron producers continuing to invest significantly in the province. In addition to an interest in natural resources, Chinese, Japanese, and other Asia Pacific-based firms have begun to show an interest in Quebec’s cultural institutions.

In 2015, Quebec saw its largest ever non-resource focused investment from the Asia Pacific when China’s Fosun International Ltd. took over ownership of Cirque du Soleil in partnership with U.S.-based TPG Capital for $1.5 billion. Such an investment marks a new focus for Chinese companies as they become increasingly interested in acquiring international arts and culture brands that they plan to introduce in China to a growing middle class that can afford to pay for entertainment and culture.

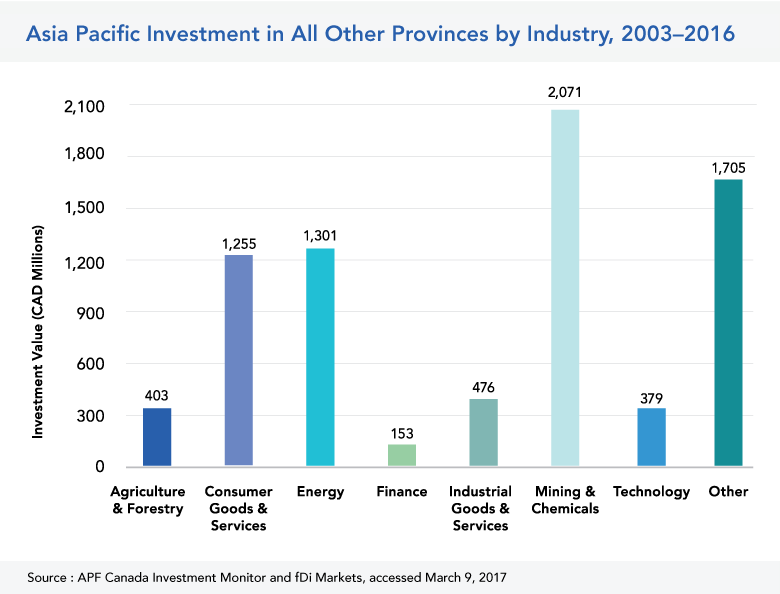

REST OF CANADA: DEFINING A FUTURE INVESTMENT RELATIONSHIP WITH THE ASIA PACIFIC

Over the past 14 years, investment into Canada’s Prairies, Atlantic Provinces, and Territories has been scattered with no discernible growth trend over time. This is not to say, however, that the potential for growth is absent. Far from it: a number of pioneering small and medium-sized investments in Canada’s smaller provinces are paving the way for Asia Pacific investors to learn how to operate in Canada’s smaller provinces.

In 2010, South Korea-based Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering signed a joint venture with the province of Nova Scotia to build a wind turbine tower and blade manufacturing facility. In 2012, Regina, Saskatchewan, saw the construction by Japan-based Fujitsu of Western Canada’s first certified Tier III data centre. In 2013, Japan-based Itochu Corporation purchased a 33.4 per cent stake in Manitoba-based HyLife Group Holdings Ltd., an integrated pork producer.

These medium-sized investments demonstrate the potential for Asia Pacific-based investors to capitalize on the skills and markets available in Canada’s smaller provinces.

BOX 5. INVESTMENT VIGNETTE: ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENT CONNECTING REMOTE COMMUNITIES IN CANADA

In 2012, the Canadian subsidiary of China-based information and communications technology firm Huawei announced a new partnership with Ice Wireless of Inuvik, Northwest Territories. The new partnership would provide 3G cellular services to rural and remote communities in Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Nunavut.

At the time of the deal, the three territories had the lowest availability and highest costs for telecom services in Canada. According to a report by the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission, residents of the Territories had 66 per cent wireless Internet access and 48 per cent 3G cellular services, whereas the rest of the country had 99 per cent access (in both cases, Internet and 3G).

Ice Wireless’s partnership with Huawei provided up-to-date networking equipment to 60,659 people across the three Territories. The planned network upgrade included expanding telecommunications services to difficult-to-service areas of the North such as Aklavik, a community with a population of 594.

Although investments by Asia Pacific-based companies in Canada’s North have been sparse to date, partnerships such as that between Huawei and Ice Wireless have the potential to transform the landscape.

Source: APF Canada Investment Monitor

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

- Provinces with the largest economies — Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec — attract the most investments from the Asia Pacific.

- Investments in British Columbia, Alberta, and Quebec are focused on natural resources.

- Investments in Ontario are focused on the automotive industry.

- The rest of Canada has yet to see a discernible growth trend in investment from Asia.

Asia Pacific Investment Strategies

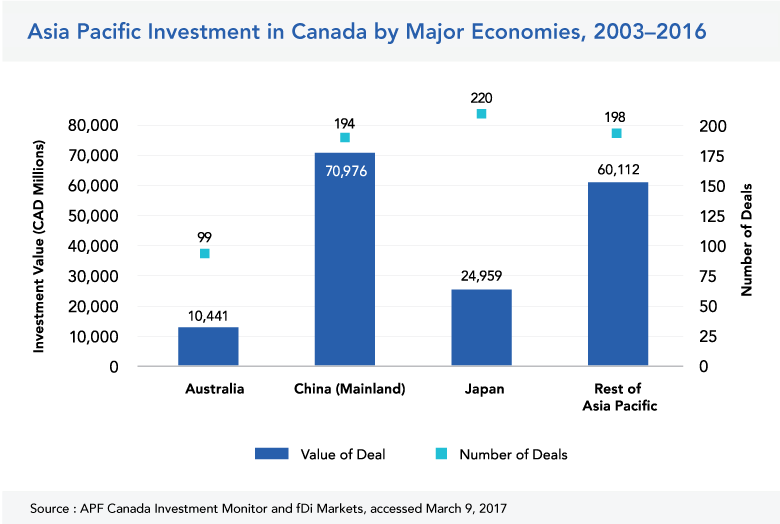

CHINA, JAPAN, AND AUSTRALIA ARE THE MAIN SOURCES OF ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENT IN CANADA

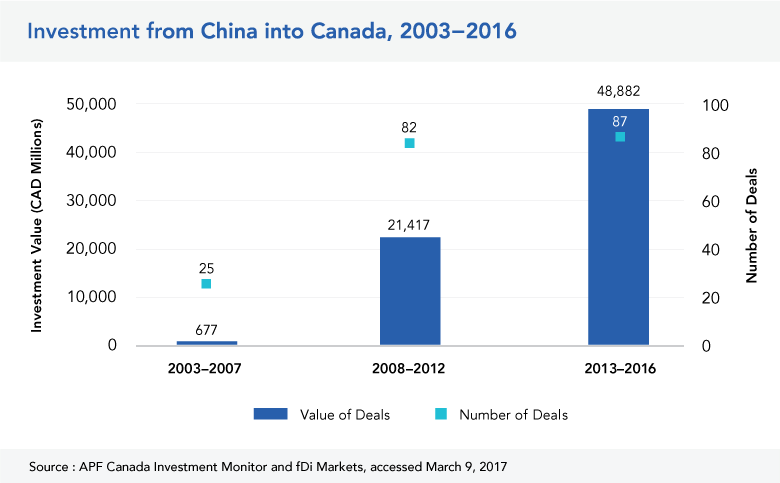

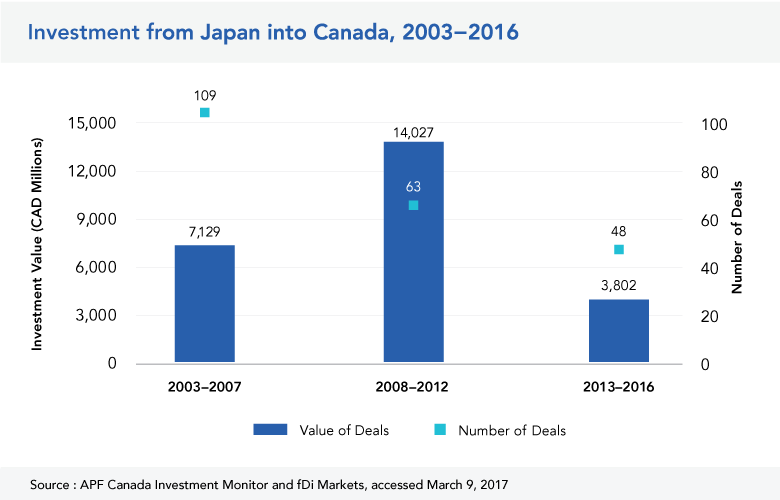

Over the past 14 years Asia Pacific investment into Canada has seen a boom led by three major Asia Pacific economies: China, Japan, and Australia. Combined, these three economies represent nearly 70 per cent of the investment flows from the Asia Pacific into Canada over this time period. While Japan led the first wave of investment from Asia Pacific into Canada in the embryonic period (2003-2007), by the rebalancing period (2008-2012) China took the lead in the second wave of investment.

CHINA GOES GLOBAL AND THE REVERBERATIONS ARE FELT IN CANADA

After just one decade of its “Go Global” policy, China quickly became a key global exporter of foreign direct investment. According to official Chinese statistics, in 2003, its annual FDI outflows were a mere US$2.9 billion, but by 2014 they had reached US$123.1 billion. [1]

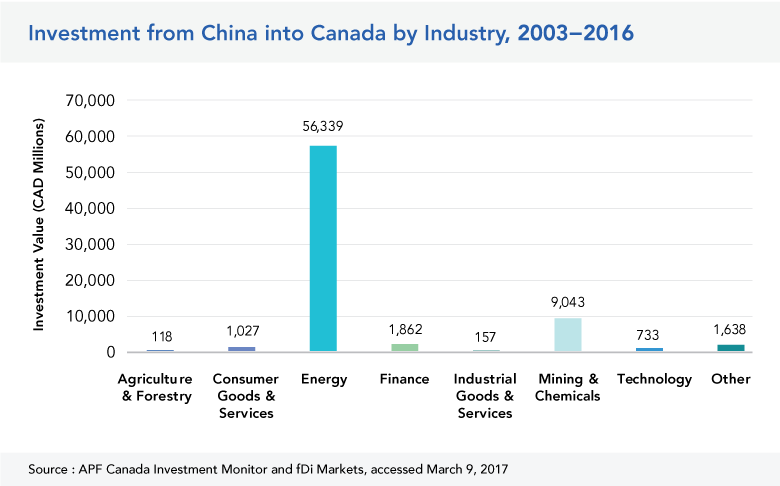

Canada is one of the main recipients of Chinese outbound FDI. The late 2000s saw a sharp rise in Chinese outbound FDI outflows to Canada (see chart below). According to Chinese statistics, by 2007, Canada was the fourth-largest recipient of Chinese capital. [2] During this time, a large portion of Chinese investment in Canada was focused on natural resources.

The most notable Chinese investment into Canada to date is the contentious $15.1-billion takeover of Canadian oil and gas company Nexen Inc. by the Chinese state-owned entity CNOOC Ltd. in 2013. This investment in particular triggered national security concerns over Chinese state investments among Canadian citizens, political leaders, and business communities. Since 2013 there has been a decline in the volume of investment from China in Canada.

However, Chinese firms are still eager to invest abroad, including in Canada. The government of China still actively encourages its businesses to invest abroad. The recent Chinese 13th Five-year Plan released in 2016 confirms this by increasing the sectors of interest for both inward and outward foreign direct investment. The government continues to facilitate outbound FDI by liberalizing policies, such as simplifying investment approval procedures, improving post-investment monitoring activities, providing tax deductions and exemptions for outbound FDI, and informing Chinese investors of overseas business opportunities. At the same time, however, some observers of Chinese FDI policy believe that China is sending somewhat mixed messages in that it is more eager to keep investment monies at home to help develop its domestic economy.

Chinese firms are recalibrating their strategy in Canada. Chinese direct investment has begun to expand into industries other than conventional resources such as technology, aviation, manufacturing, food, consumer goods, and cultural entertainment (see graph below). Even though there has been an expansion to investment in other industries in Canada, investment projects have been dropping over the past few years, mainly because of the increasing competition Canada is facing from other countries around the world.

The Government of Canada, however, has been working to maintain China’s investment relationship with Canada. In 2012 Ottawa and Beijing signed a Canada-China FIPA that came into force in October 2014. This FIPA, as well as the current government’s intentions to strengthen ties between the two countries, is expected to encourage more Chinese investment into Canada in the future. However, as China’s focus shifts to developing its One Belt and One Road investment strategy, an initiative led by China to develop greater connectivity and co-operation in Eurasia, Canada will have to work hard to grow the Canada-China investment relationship.

JAPAN'S POST BUBBLE INVESTMENT PUSH IN CANADA

As the third-largest economy in the world after the U.S. and China, Japan is a substantial player in the world’s foreign direct investment outflows. According to United Nations statistics, in 2015, Japan invested almost US$130 billion into the world economy, making it the second-largest investor after the U.S. [3]

Japan’s “bubble economy” in the 1980s when real estate and stock markets were greatly inflated saw rapid growth in Japanese outward FDI. This continued until the early 1990s when the “bubble economy” burst. Since the 2000s, Japanese investment has been growing, although not as rapidly as during its “bubble economy” years. Even so, Japan has still been a major presence in the global economy.

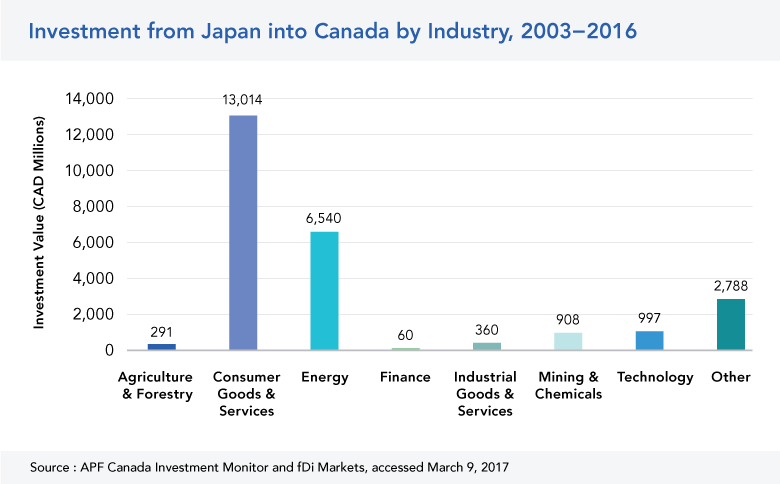

In Canada, Japan is a significant contributor of FDI. Over the past 14 years, Japanese investments in Canada have grown significantly (see chart below). A number of Japanese companies have focused on Canada as an investment destination rather than its traditional investment partner to Canada’s south, the U.S., because of the lower operating costs offered in Canada. [4]

In Canada, Japanese companies have invested heavily in the automobile and electronics industries, although since the late 2000s, more focus has been placed on natural resources — such as agriculture and forestry as well as mining and chemicals — because of the shortage of natural resources on the Japanese archipelago. One of the largest investments in natural resources was the acquisition by Japex Montney of 10 per cent of the natural gas assets of Progress Energy Canada in 2013.

Compared to other developed countries, Japanese policy has not been as active in pushing for investment agreements with other countries, especially with countries in which Japan has invested a considerable amount. [5] To this day, Japan has still not signed a bilateral investment treaty with Canada. There have been negotiations toward a Canada-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), which focuses on boosting trade and investment between the two countries. The last of these negotiations took place in November 2014, [6] as both countries shifted their focus to completing the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations.

The signing of the Canada-Japan EPA could provide Japanese investors in Canada with better opportunities and safety measures and further strengthen the two countries’ investment partnership.

BOX 6. INVESTMENT VIGNETTE: BUILDING ONTARIO'S AUTO INDUSTRY

Over the past two decades, Japanese investment in the province of Ontario has helped build a strong automotive industry. Under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Ontario plays host to Japanese automotive firms looking to access not only the Canadian market but the United States and Mexico as well. Leading Japanese firms such as Toyota and Honda have a long track record in the province of making new investments as well as expanding investment in current production plants.

Japanese automotive firms choose to locate their production facilities in Ontario not only due to NAFTA but also because of the highly skilled workforce available and the presence of globally recognized suppliers. In addition to these assets, Japanese firms operating in Ontario also benefit from Ontario’s network of universities and automotive research centres. This symbiotic relationship serves to reinforce the investment relationship between the province of Ontario and Japan.

A prime example of this is Toyota’s 2008 $1.2-billion investment in Woodstock, Ontario. According to a recent report by the Automotive Policy Research Centre, what cemented the Ontario location for Toyota was the fact that the new plant could be managed out of Toyota’s current facility in Cambridge, Ontario, and that the plant would be able to tap into Ontario’s pool of award-winning workers.

Source: APF Canada Investment Monitor

AUSTRALIA: MULTINATIONAL MINING CORPORATIONS EXTEND REACH INTO CANADA

Australia, although a smaller nation both in terms of GDP and population than Canada, contributes a larger share of outward FDI to other nations than Canada. In 2015, Australia’s rank in global outward FDI stock was 17th; Canada came in 8th. [7]

The largest destinations for Australian outward FDI have traditionally been New Zealand, the U.S., and the U.K. Over the past decade, Australian outward investment to other Asian economies increased by almost five times over the previous decade. The main reasons for this have been proximity, cheaper costs, and pursuing the wealth of opportunities developing economies in Asia offer.

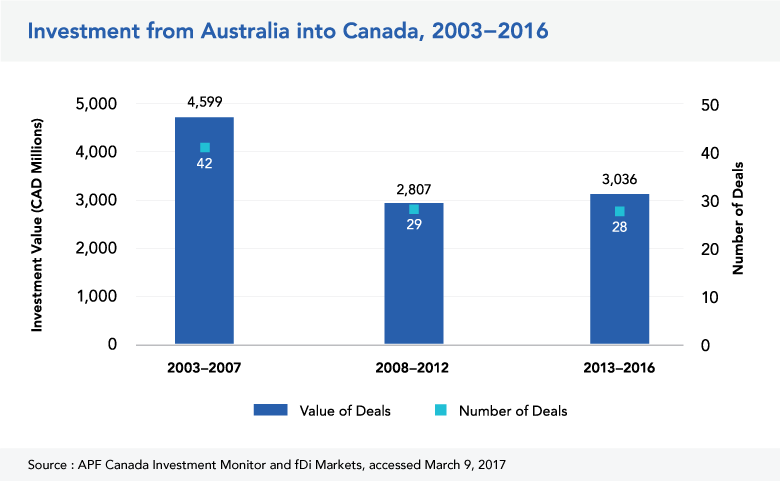

Although Australia’s FDI into Asian economies has been on the rise, its total outward FDI outflows have over the past decade have been on a decline. In 2005, total Australian investment abroad amounted to AU$100.5 billion. In 2010, it dropped down to AU$87.4. [8] And 2014 was one of Australia’s worst years for FDI outflows; according to the United Nations, the value of outward FDI in that year amounted to US$3 billion. [9] According to data from the Investment Monitor, Australian FDI in Canada has been relatively stable. However, the past two years have seen a sharp decrease in Australian investment into Canada, with 2016 having the lowest Australian investment into Canada since 2003.

Similar to Japan, a considerable amount of investment from Australia into Canada is in resources and energy (see chart below). Well-known Australian companies that have actively invested in Canadian resources and energy for a long time are BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto. More recently, Australian mining equipment technology and services firms such as AMC Consultants and OSD Pipelines have invested in Canada. Large Australian firms, such as Macquarie Bank and Plenary Group, have also set their sights on the Canadian infrastructure market because of Canada’s renowned leadership in public-private partnerships.

With the current version of the Trans-Pacific Partnership not moving forward, Australia will be at an investment disadvantage with some TPP member states such as Canada; however, Australia may be able to still create a beneficial relationship with TPP members through the proposed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which includes Japan, ASEAN nations, China, India, South Korea, and New Zealand. This agreement hopes to promote, protect, facilitate, and liberalize investment between all member states.

Australia also hopes to continue liberalizing investment through free trade agreements with other countries it has strong trade and investment ties with. Although Canada and Australia have had strong ties for many decades, there have not yet been negotiations between the two countries on a bilateral FTA or FIPA. It may be beneficial for Canada to push for negotiations with Australia on an agreement that helps promote and protect investment between the two countries now that the ratification and entry into force of TPP looks unlikely.

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

- The Asia Pacific’s major economies of China, Japan, and Australia are the leading sources of investment in Canada.

- Chinese investment in Canada picked up substantially starting in the late 2000s.

- Japan continues its decades-long relationship with Canada’s automotive sector.

- Australian investment in Canada has been relatively consistent over the past decade, with the exception of a sharp decline seen in the past two years.

ENDNOTES

[1] MOFCOM. 2014 statistical bulletin of Chinese outward foreign direct investment.

[2] MOFCOM. 2007 statistical bulletin of Chinese outward foreign direct investment.

[3] UNCTAD. World investment report 2016.

[4] Global Affairs Canada. Report of the joint study on the possibility of a Canada-Japan economic partnership agreement.

[5] Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry Japan. White paper on international economy and trade.

[6] Global Affairs Canada. Canada-Japan economic partnership agreement.

[7] Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Australia. Australia and foreign investment.

[8] Treasury Shared Services Australian Government. Australia’s international investment position.

[9] UNCTAD. World investment report 2016.

Conclusion

Foreign direct investment from the Asia Pacific in Canada is becoming an increasingly important source of foreign capital for Canada’s economy. Not only does foreign direct investment from the region provide the capital necessary to expand or start up businesses in Canada, it also lends itself to the transfer of management know-how and technological expertise due to the controlling interest (10% investment or greater) nature of the relationship. This infusion of financial and human capital can help Canada increase its productivity and make Canadian businesses more internationally competitive. From a long-term perspective, the addition of Asia Pacific-based management and technological expertise into Canada’s business sector can also aid Canadian firms looking to enter markets in the Asia Pacific.

As the centre of the global economy continues to shift towards the Asia Pacific, Canada needs to keep pace with other countries in developing its business ties with the region. A good way to strengthen business ties across the pacific is by fostering two-way investment. To date, in Canada, we understand very little about the impact of our two-way investment relationship with the Asia Pacific. More detailed knowledge about the volume, scale, scope and impact of Asia Pacific investment in Canada can better inform policy decisions and the public.

The Asia Pacific Foundation Canada Investment Monitor seeks to lay the groundwork for evidence-based decision-making by providing the public with a growing data set of investment deals by Asia Pacific-based companies in Canada and, in subsequent years, by Canadian-based companies in the Asia Pacific. By nurturing this resource, APF Canada hopes to provide a basic set of facts about the number, size, and distribution of investment deals between Canada and the Asia Pacific that researchers, the public, and government can use to better understand how best to grow the investment relationship.

Sources

Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2016. 2016 national opinion poll: Canadian views on Asia. https://www.asiapacific.ca/surveys/national-opinion-polls/2016-national-opinion-poll-canadian-views-asia

Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2016. Iris Jin. Differing methodologies causing stark discrepancies in Chinese and Canadian FDI statistics. http://www.asiapacific.ca/blog/differing-methodologies-causing-stark-discrepancies-chinese

Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2016. Yingqiu Kuang. Contemporary China series: State-owned enterprises at a cross roads: Key features of China’s new SOE reform. http://www.asiapacific.ca/research-report/contemporary-china-series-state-owned-enterprises-cross

Eugene Beaulieu and Matthew M. Saunders. The impact of foreign investment restrictions on the stock returns of oil sands companies. University of Calgary, School of Public Policy, Vol. 7, Issue 16, June 2014.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Australia. Accessed March 2017. Australia and foreign investment: Where does Australia invest? http://dfat.gov.au/trade/topics/investment/Pages/where-does-australia-invest.aspx

Global Affairs Canada. 2012. Report of the joint study on the possibility of a Canada-Japan economic partnership agreement. http://www.international.gc.ca/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/japan-japon/study-report_rapport-etude.aspx?lang=eng#t13

Global Affairs Canada. Canada-Japan economic partnership agreement. http://international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/japan-japon/fta-ale/background-contexte.aspx?lang=eng

Investopedia. Green field investment. Accessed March 2017. http://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/greenfield.asp

Investopedia. Mergers and Acquisitions: Definition. Accessed March 2017. http://www.investopedia.com/university/mergers/mergers1.asp

Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry Japan.2008. White paper on international economy and trade. http://www.meti.go.jp/english/report/downloadfiles/2008WhitePaper/4-4.pdf

MOFCOM. December 2008. 2007 statistical bulletin of Chinese outward foreign direct investment. http://images.mofcom.gov.cn/hzs/accessory/200811/1226887378673.pdf

MOFCOM. September 2015. 2014 statistical bulletin of Chinese outward foreign direct investment. http://hzs.mofcom.gov.cn/article/date/201510/20151001130306.shtml

NBS, MOFCOM, and SAFE. 2016. 2015 Statistical bulletin of China’s outward foreign direct investment.

Rhodium Group. 2016. Two-way street: 25 years of US-China direct investment. http://rhg.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/TwoWayStreet_FullReport_En.pdf

Treasury Shared Services Australian Government. 2009. Australia’s international investment position. https://cdn.tspace.gov.au/uploads/sites/79/2015/11/FIRB-Annual-Report-2009-10_Chapter_4.pdf

UNCTAD. 2016. World investment report 2016. http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2016_en.pdf

Appendix

METHODOLOGY

Please see the methodology and glossary section.

BOXES

Box 1. Cross-Border Investment and FDI

Box 2. Investment Types

Box 3. Investment Vignette: Pulling the Welcome Mat out from under SOE’s Feet

Box 4. Investment Vignette: Moulding a New Relationship between First Nations and Asia Pacific Businesses

Box 5. Investment Vignette: Asia Pacific Investment Connecting Remote Communities in Canada

Box 6. Investment Vignette: Building Ontario’s Auto Industry

FIGURES

Figure 1. Canada’s inward foreign direct investment stock by region, 1987-2015 (per cent)

Figure 2. Asian investment in Canada, 2003-2016

Figure 3. Asia Pacific investment in Canada’s natural resource-based industries, 2003-2016

Figure 4. Asia Pacific investment in Canada’s non-natural resource-based industries, 2003-2016

Figure 5. Asia Pacific greenfield and brownfield investments in Canada, 2003-2016

Figure 6. Asia Pacific SOE investment in Canada, 2003-2016

Figure 7. Canadian preferences for private companies and state-owned companies

Figure 8. Asia Pacific investment by province, 2003-2016

Figure 9. Asia Pacific investment in B.C. by Industry, 2003-2016

Figure 10. Asia Pacific investment in Alberta by industry, 2003-2016

Figure 11. Asia Pacific investment in Ontario by industry, 2003-2016

Figure 12. Asia Pacific investment in Quebec by industry, 2003-2016

Figure 13. Asia Pacific investment in all other provinces by industry 2003-2016

Figure 14. Major Asia Pacific economy investment in Canada, 2003-2016

Figure 15. Investment from China into Canada, 2003-2016

Figure 16. Investment from China into Canada by industry, 2003-2016

Figure 17. Investment from Japan into Canada, 2003-2016

Figure 18. Investment from Japan into Canada by Industry, 2003-2016

Figure 19. Investment from Australia into Canada, 2003-2016

Figure 20. Investment from Australia into Canada by Industry, 2003-2016

TABLES

Table 1. Number of Asia Pacific investment deals in Canada, 2003-2016

PARTNERS AND SPONSORS

Please see the partners and sponsors section.

ADVISORY COUNCIL

Please see the advisory council section.

About APF Canada

The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada is dedicated to strengthening ties between Canada and Asia with a focus on expanding economic relations through trade, investment and innovation; promoting Canada’s expertise in offering solutions to Asia’s climate change, energy, food security and natural resource management challenges; building Asia skills and competencies among Canadians, including young Canadians; and, improving Canadians’ general understanding of Asia and its growing global influence.

The Foundation is well known for its annual national opinion polls of Canadian attitudes regarding relations with Asia, including Asian foreign investment in Canada and Canada’s trade with Asia. The Foundation places an emphasis on China, India, Japan and South Korea while also developing expertise in emerging markets in the region, particularly economies within ASEAN.

Visit APF Canada at www.asiapacific.ca.