A Message from the President & CEO

Looking back now, more than one year after the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 served as a stark reminder of how interconnected the world economy has become. Despite the current economic challenges, the flow of capital and goods across borders continues to serve as the lifeblood of the global economy. As we slowly emerge from the current public health and economic crisis, now more than ever, Canada needs to consider how to strategically engage with the Asia Pacific region for its economic recovery in the post-COVID-19 environment.

Canada has been fortunate to benefit from the continuously strong trade and investment ties with its traditional economic partners, such as the United States and Europe. However, the pandemic has taught us that diversification should and will remain a key pillar for Canada’s economic prosperity in the long term. The Asia Pacific’s relative resiliency throughout the crisis has demonstrated the need for Canada to deepen and diversify its engagement within the region.

Since 2017, APF Canada has been publishing reports on the bilateral foreign direct investment (FDI) flows between Canada and the Asia Pacific, with the ultimate goal of facilitating evidence-based policy-making and public discourse on Canada’s engagement with the region. In the fifth year of its iteration, the Investment Monitor continues to track the two-way investment ties at the national, provincial, and city levels between Canada and the Asia Pacific. Last year, the Investment Monitor Annual Report examined the connections between Canada’s free trade agreements with Asia Pacific economies and FDI.

In 2021, the Investment Monitor turns its attention to the investment opportunities and challenges for Canadian companies in the Asia Pacific, particularly in digital, clean energy, and R&D-engaged industries. As recovery is on the horizon with the increasing availability of vaccines in the coming months, it is important to understand how the investment landscape is shifting in the region and the potential implications for Canada. This report provides a timely analysis of the recovery strategies of South Korea, India, Singapore, and Australia and how they could present opportunities for Canadian companies.

On behalf of APF Canada, I would like to acknowledge the efforts of those involved in producing this report, especially our partner, The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary, and our sponsors, Export Development Canada, the Government of British Columbia, and Invest in Canada. I would like to extend my appreciation to our Advisory Council Members for their valued feedback. I would also like to thank the many investment attraction agencies across Canada which have taken the time to speak with the research team and provide on-the-ground insights.

And finally, I would like to thank the members of our APF Canada research team who were responsible for writing and finalizing this report: Jeffrey Reeves, Vice President, Research; Charles Labrecque, Research Manager; Pauline Stern, Program Manager, Business Asia; Isaac Lo, Project Specialist, Trade and Investment; our Post-Graduate Research Scholar and Junior Research Scholars, Olivia Adams, Charlotte Atkins, and Rachelle Taheri; and, APF Canada’s communications team for editing and designing the final publication, Michael Roberts, Communications Manager, and Jamie Curtis, Graphic Designer.

Executive Summary

The Asia Pacific region is home to a large number of the world’s fastest-growing economies, making it an increasingly important investment relationship – both in terms of opportunities for Canadian companies in the Asia Pacific, and Asia Pacific investment in Canada.

However, despite the importance of the relationship between Canada and the Asia Pacific region, there is a lack of reliable, detailed public data on investments. APF Canada’s Investment Monitor fills this gap and delves deeper into the investment relationship. The Investment Monitor aggregates data from the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s legacy data of investment deal announcements, along with third-party sources and metasearch engines (see methodology section for more details).

Each year the Investment Monitor Report has an annual theme. This year’s focuses on Canada’s investment opportunities in the Asia Pacific region post- COVID-19. Specifically, this report looks at the recovery plans of four select Asia Pacific economies, and examines what investment opportunities they may hold for Canadian companies in the digital, clean energy and R&D-engaged industries.

This annual report presents the following:

- General trends in the Canada–Asia Pacific foreign direct investment relationship, from 2003 to 2020;

- The recovery plans of four select economies – South Korea, Australia, India and Singapore – and potential investment opportunities for Canadian companies;

- Inbound and outbound investment relationships at the national, provincial and city levels.

Investment Monitor 2021: Key Takeaways

SOUTH KOREA, INDIA, AUSTRALIA, AND SINGAPORE HAVE INCORPORATED GOVERNMENT SPENDING PROGRAMS TO BOOST COMPETITIVENESS IN THEIR DIGITAL, CLEAN ENERGY AND R&D-RELATED INDUSTRIES. THESE PRESENT SIGNIFICANT INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES FOR CANADIAN COMPANIES IN THE POST-COVID CLIMATE.

Of the four economies examined, South Korea has the most ambitious clean energy and digital programming, with C$48B invested towards achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, and C$16.7B invested in the integration of 5G and AI in the private sector. India has the most ambitious R&D programming, with C$8.6B going towards the National Research Foundation.

OUT OF THE FOUR SELECTED ECONOMIES, AUSTRALIA RECEIVED THE HIGHEST CANADIAN OUTBOUND INVESTMENT IN DIGITAL, CLEAN ENERGY, AND R&D-RELATED INDUSTRIES.

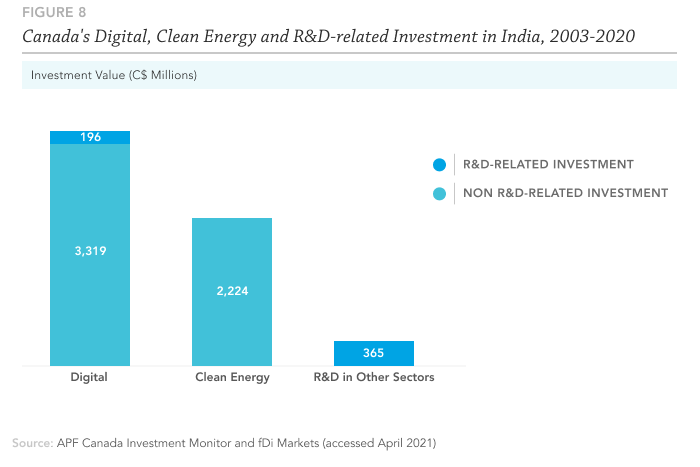

Specifically, in the last 18 years, Canadian companies have invested C$3.7B in Australia’s digital sector, C$2.4B in the clean energy sector, and C$795M in R&D-related investments. This is followed by India with C$6.2B invested in all three industries.

IN 2020, CANADA RECEIVED A TOTAL OF C$6.4B OF FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT FROM THE ASIA PACIFIC REGION.

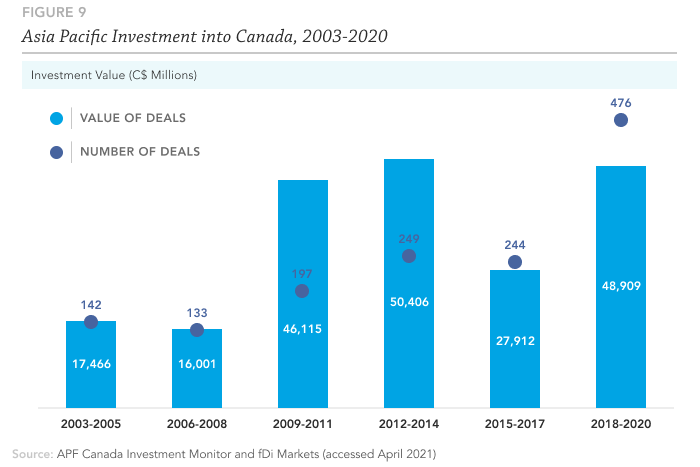

This marks the second consecutive year of decrease in the value of inward FDI from C$9B in the previous year. However, in the time period of 2018 to 2020, Asia Pacific investments into Canada totalled C$48.9B, having rebounded from the low-end of C$27.9B in the previous three-year period.

DESPITE THE DROP IN YEAR-ON-YEAR INBOUND INVESTMENT FLOW, ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENT ACTIVITIES HAVE CONTINUED TO CLIMB, REACHING AN 18-YEAR RECORD WITH 181 DEALS.

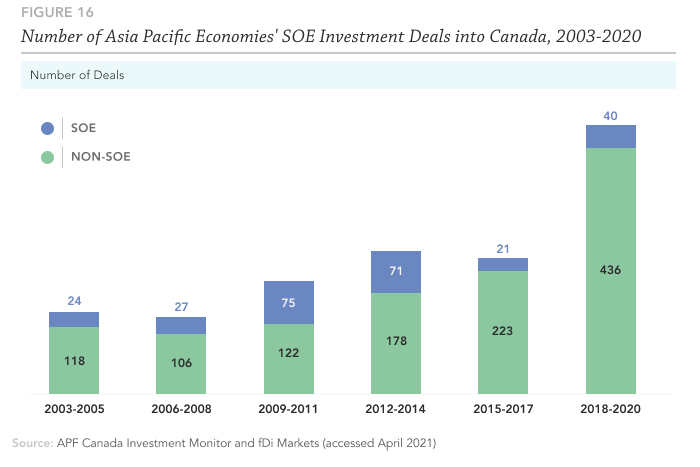

The increasing investment activity is also reflected in the number of deals made on a three-year interval basis. From 2018 to 2020, Canada saw the number of deals reach an all-time high of 476, compared to other three-year periods. For example, from 2015 to 2017 there were 244 deals.

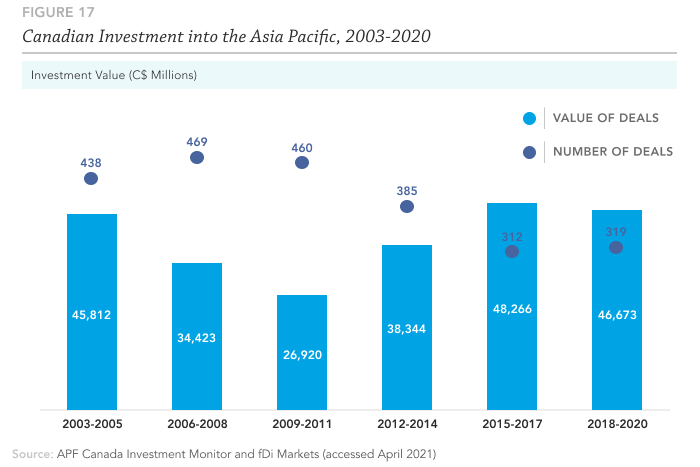

WHILE INBOUND CANADIAN FDI FLOW SAW A YEAR ON-YEAR DECREASE IN 2020, OUTBOUND FLOW FROM CANADIAN COMPANIES TO THE ASIA PACIFIC REGION REMAINS HIGHLY RESILIENT DESPITE THE ECONOMIC HEADWIND.

In 2020, Canadian companies invested C$16.8B worth of capital in the region via 89 deals. Canada’s outbound flow in 2020 represented a C$5.3B increase in value from 2019.

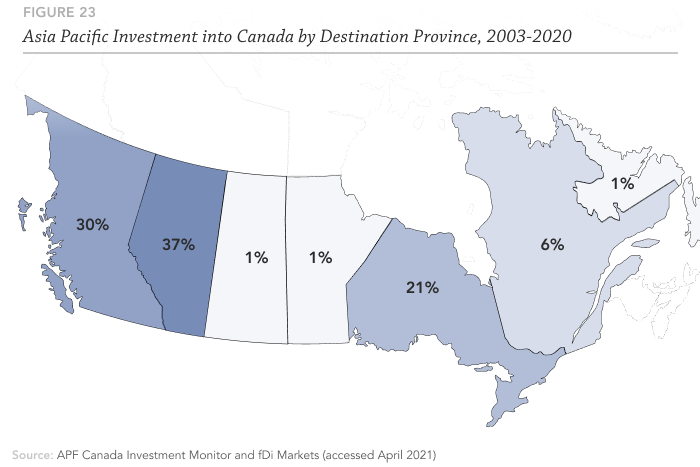

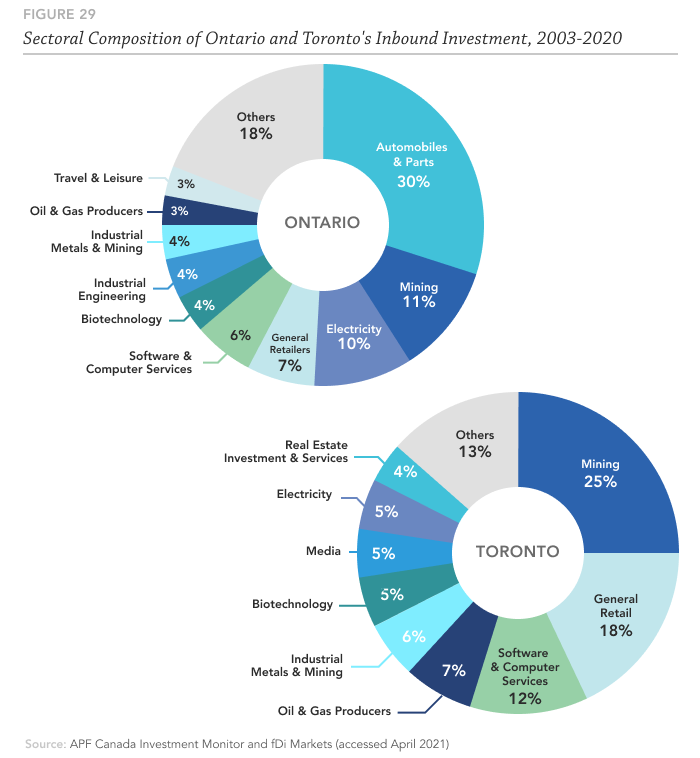

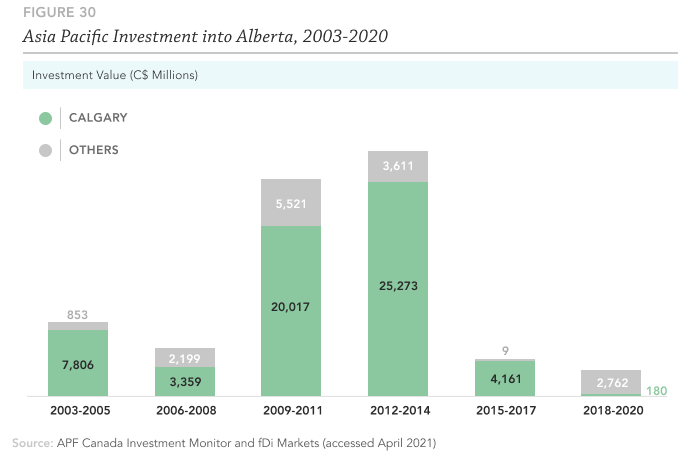

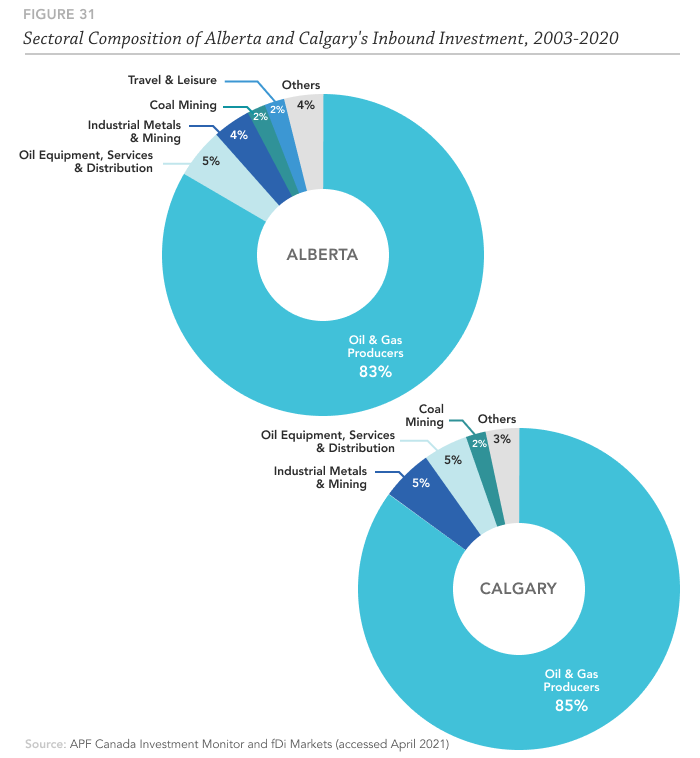

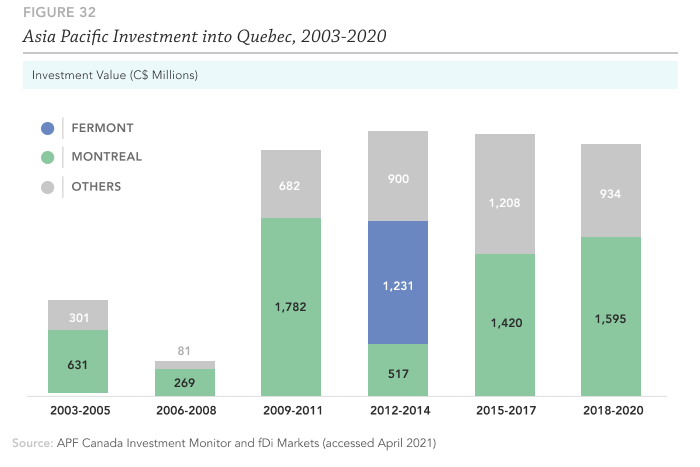

AT THE SUBNATIONAL LEVEL, ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENTS INTO CANADA REMAIN HIGHLY CONCENTRATED IN THE FOUR MOST POPULOUS PROVINCES – ALBERTA, BRITISH COLUMBIA, ONTARIO, AND QUEBEC.

Together, the four provinces accounted for 94 per cent of Asia Pacific investment flow into Canada in the last 18 years. The two western provinces in particular – Alberta and British Columbia - alone account for 67 per cent of the total inbound flow.

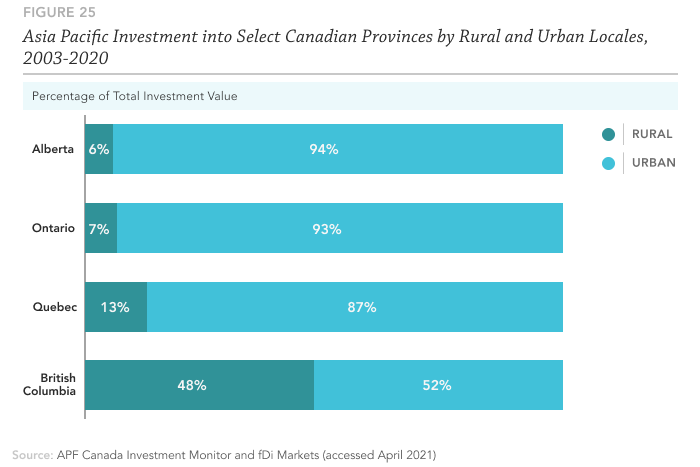

THE BULK OF INBOUND INVESTMENT FROM THE REGION IN THE LAST 18 YEARS HAS BEEN DIRECTED TO CANADA’S LARGEST CITIES AND TOWNS, WITH URBAN INVESTMENTS ACCOUNTING FOR 79 PER CENT OF THE DOLLAR VALUE CANADA RECEIVED.

With that being said, 75 rural communities across Canada have also seen Asia Pacific investments, with C$42B worth of capital received from 2003 to 2020.

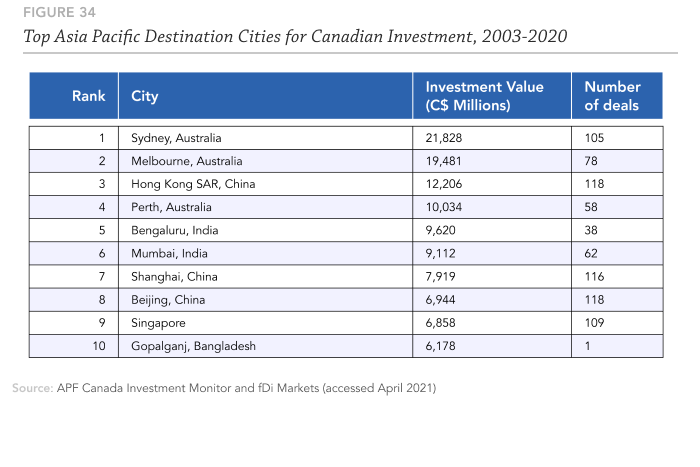

SINCE 2003, CANADIAN COMPANIES HAVE INVESTED IN 496 CITIES AND MUNICIPAL-LEVEL REGIONS ACROSS THE ASIA PACIFIC REGION, FROM LARGE URBAN CLUSTERS LIKE SYDNEY, BEIJING, MUMBAI, AND BENGALURU TO SMALLER COMMUNITIES, SUCH AS GOPALGANJ, REPRESENTING THE DEPTH AND BREADTH OF CANADIAN ECONOMIC ENGAGEMENT IN THE REGION.

While Australian cities – namely Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth – are among Canada’s top investment destinations in the region, collectively having received C$51B in Canadian investments, Mumbai and Bengaluru are the rising stars. The two cities saw the highest amount of Canadian investment in 2020, with Mumbai receiving C$2.9B and Bengaluru C$2.6B.

Introduction

INVESTMENT TRENDS IN 2020

2020 was a year unlike any other. The spread of COVID-19, which accelerated in the early months of 2020, continues to pose a significant threat to economies worldwide. Globally, the disease has claimed more than 2.5 million lives at the time this report was written.[1] As public health authorities continue to battle the outbreak, the economic pain has been immediate and devastating. The World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects estimated that global gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 dropped by 4.3 per cent.[2] The pandemic-induced economic downturn also slashed global FDI flows. The latest data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), released in January 2021, showed that global FDI in 2020 declined by 42 per cent from the previous year.[3]

The first to be hit by the pandemic, the Asia Pacific region saw significant economic damage, with COVID-19 inducing the first region-wide economic contraction in nearly six decades.[4] Despite this, some Asia Pacific economies have proved resilient. The World Bank estimates that emerging economies in the East Asia and Pacific region maintained a positive year-on-year GDP growth rate in the past year at 0.9 per cent, with a forecasted rebound of 7.4 per cent in 2021. The region’s economic resiliency is reflected in its FDI inflows. UNCTAD estimates that developing economies in Asia only saw a 4 per cent decrease in FDI inflow from 2019 to 2020, compared to the drastic drop of 46 per cent in North America.[5]

Notably, China overtook the United States as the world’s largest FDI recipient economy in 2020, as it saw a 4 per cent increase in FDI inbound flow. And despite India’s economy facing an estimated 9.6 per cent GDP contraction in the past year, inbound flow of FDI into the economy increased by 13 per cent. The Asia Pacific’s economic resiliency points to the growing importance of Canada’s economic engagement with the region, particularly in the context of post-COVID recovery.

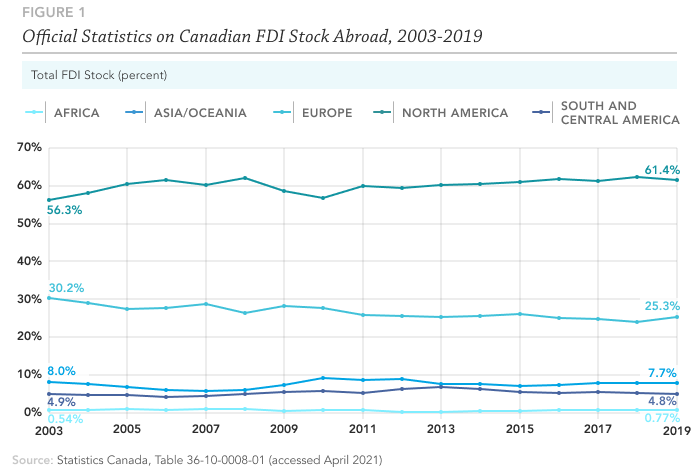

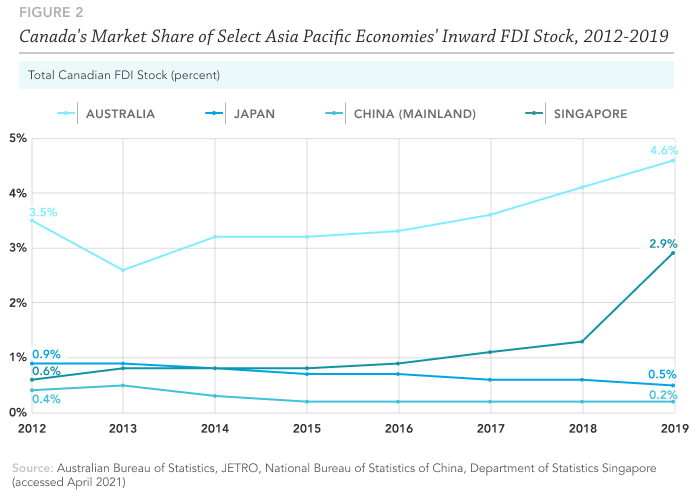

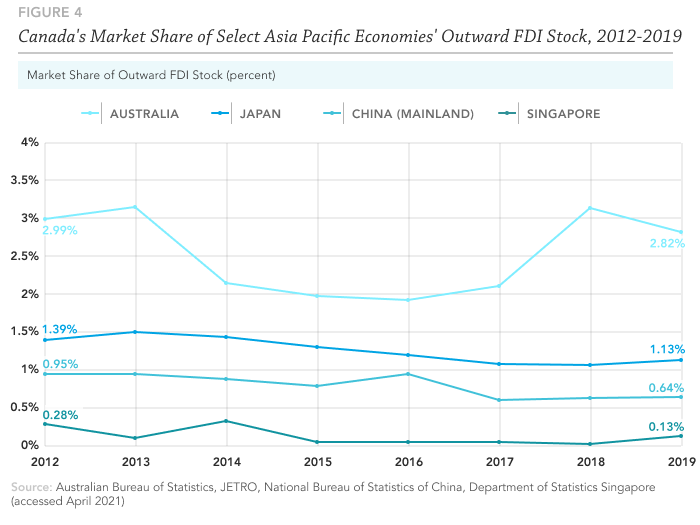

While the Asia Pacific region still accounts for a relatively small share of Canada’s overall FDI stock (see Box 1 for the definition of FDI stock), reflecting Canada’s historical ties with Europe and the United States, its share has grown. From 2015 to 2019, the proportion of Canadian FDI stock in the region has increased from 8.8 per cent to 9.8 per cent and Asian investors’ FDI stock in Canada has increased from 6.8 per cent to 7.7 per cent.

HOW CANADA STACKS UP IN ITS INVESTMENT RELATIONSHIPS WITH THE ASIA PACIFIC

FDI is central to the Canadian economy. Statistics Canada, the country’s national statistical agency, provides annual data on Canada’s investment position vis-a-vis its economic partners at the national level. The latest official statistics show that Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific continues to comprise only a small percentage of total Canadian outbound FDI stock as well as the Asia Pacific’s inbound FDI.

Between 2003 and 2019, Canada’s outward investment in the region as a percentage of total FDI peaked at 9.1 per cent in 2010 and has since fallen to approximately 7.7 per cent in 2019. The declining level of Canadian investment stock in the region is also reflected in Canada’s low share of inbound investment stock from some Asia Pacific economies. China, Japan, Australia, Singapore, and South Korea remain among the largest recipients of Canadian FDI in the Asia Pacific. However, Canadian investment represents a relatively small proportion of their respective total inbound FDI stock, ranging from 0.2 per cent to a maximum of 4.6 per cent.

Official statistics also reveal that Canada is not a large recipient of FDI from Asia Pacific economies. The largest Asia Pacific economies – including Australia, China, Japan, South Korea and Singapore – collectively made up only 7.1 per cent of total Canadian inward FDI stock in 2019. However, it is worth noting that inbound investment from key economies in the Asia Pacific is increasing. For example, Chinese investment in Canada increased by approximately C$1.6B between 2018 and 2019.

While Statistics Canada provides a comprehensive overview of Canada’s investment relations with Asia Pacific economies, its data relies primarily upon its surveys of Canadian businesses, foreign firms, and reports from government bodies such as the Bank of Canada to generate national-level investment data. With the lack of transaction-specific information, the official statistics are unable to provide data that supports analyses of investment trends at the subnational-level, by sector and industry, or by ultimate source and destination. Therefore, the information published by Statistics Canada can provide a useful overview of the investment relationship between Canada and the largest Asia Pacific economies, but its data cannot be used to discover trends at the industry or regional levels.

INVESTMENT MONITOR SUPPLEMENTS OFFICIAL STATISTICS

The Asia Pacific is a dynamic economic region that plays a crucial role in the development of the global economy. However, official statistics do not necessarily offer Canadians a holistic view of Canada’s investment ties with the Asia Pacific. The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) recognized this gap and began the Investment Monitor project. This project is uniquely able to provide a comprehensive understanding of Canada-Asia Pacific investment’s scope and scale through its reliance on transaction-level data. APF Canada’s Investment Monitor uses publicly available investment information, in addition to its own legacy data to provide records of investment that span almost two decades. The Investment Monitor Report is an effort by APF Canada to provide in-depth analysis and insights on Canada’s investment relationship with Asia. This includes an overview of the major locations, investors, and sectors shaping Canadian engagement with the Asia Pacific region.

When examining FDI, it is important to understand the difference between stock and flow. Stock refers to the total quantity of investment in an economy at a given time. Flow refers to movements of quantities in and out of the stock. There are two types of flows: an inflow marks an increase in the overall stock value, while an outflow marks a deduction. The difference between the two is referred to as net inflow. A positive net inflow indicates the stock is rising, whereas a negative net inflow indicates the stock is falling.

On the whole, FDI stock values show the overall presence of FDI in an economy, whereas FDI flows signal the economic developments and the attractiveness of a destination economy at a given time.[6] For example, due to the pessimistic market outlook of investors during the COVID-19 pandemic, many foreign investments have been withdrawn. These reversals represent FDI outflows. If FDI outflows were to eclipse FDI inflows in 2020, this would translate into a negative net inflow and thus a reduction in the overall level of FDI stock. Together, these indicators can help policymakers and investors gain a fuller picture of FDI trends as well as gaps and opportunities.

Foreign investments can be divided into two major groups: 1) foreign portfolio investment (FPI) and 2) foreign direct investment (FDI). Both methods are essential to global economic development and trade, but FDI is considered to be a more stable form of investment with long-term benefits.

Foreign Portfolio Investment

FPI is a short-term investment by a resident or enterprise of one economy into a financial asset of another economy. FPI may take the form of equity, debt securities or loans but does not grant the investor a controlling stake in the enterprise. FPI investments are sometimes viewed as more volatile than FDI, since without a controlling stake or long-term interest in an asset, the investor can trade or liquidate the investment at any time for short-term return.

Foreign Direct Investment

FDI is a long-term or lasting-interest investment by a resident or enterprise of one economy into a tangible asset of another economy. An investment is considered to meet the threshold of FDI when it grants the investor at least 10 per cent of the equity or voting shares of the enterprise. Meeting this threshold is deemed to grant the investor a “controlling interest” in the foreign enterprise, and is what distinguishes FDI from FPI.

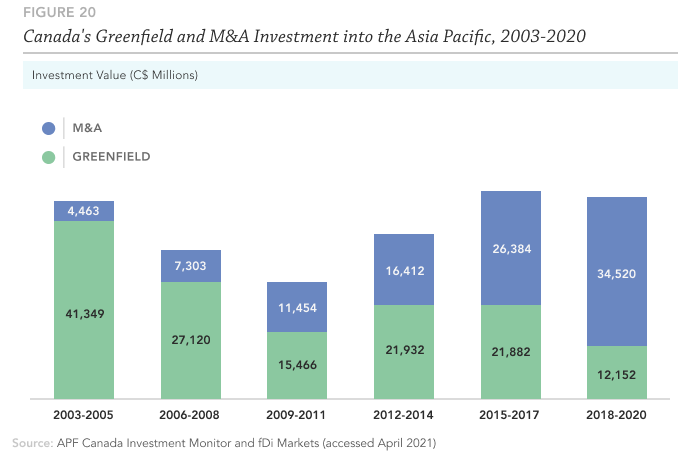

For the investor, direct investment is a long-term business undertaking with which comes more risk and commitment than foreign portfolio investments. This means that direct investment is not only a capital transfer, but also a transfer of technology, knowledge, management and organizational skills. There are two broad categories of FDI investments: greenfield, which refers to the establishment of new operations in a foreign company, and mergers and acquisitions, which happen when one company combines with another.

The Opportunities and Challenges for FDI in a Post-COVID Economy

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

- Canadian outbound FDI in the Asia Pacific region remains resilient despite the pandemic, having increased from C$11.5B in 2019 to C$16.7B in 2020, and it will be an important pillar for Canada’s FDI recovery.

- Looking at select Asia Pacific economies’ stimulus packages and budgets, there has been a focus on digital, green, and innovation-led recovery. This also aligns with the Canadian Industry Strategy Council’s recovery vision, presenting potential investment opportunities in desired sectors of focus.

- This chapter specifically focuses on opportunities in South Korea, India, Australia, and Singapore. These respective governments are reigniting their economies via substantial investments in their digital and clean energy sectors, which may prove a promising investment opportunity for Canadian companies.

- Other than the digital and clean energy sectors, South Korea, India, Australia, and Singapore are also emerging innovation hubs. With robust government support in R&D capacity across sectors, these economies present opportunities for Canadian companies looking to expand their own R&D activities.

- Despite the opportunities, these economies have also implemented varying levels of protectionist measures, such as increased FDI screening and prioritization of domestic firms in government support programs. Canadian companies may also be exposed to greater regulatory risks, given the increase in public skepticism over foreign investments, particularly via mergers and acquisitions.

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? FDI IN POST-RECESSION RECOVERIES

COVID-19 provided an economic nosedive unlike any we have seen in recent memory; in March 2020 economies across the world were at various stages of grinding to a halt. While it may appear that such an event is nothing like past recessions, one thing does remain constant: a crisis is also an investment opportunity. This chapter will discuss the rebound in inbound and outbound FDI that occurred in Canada after the financial crisis of 2008-09 and the commodities recession of 2015, and what they may tell us about the prospects for deal flow in 2021/22. Additionally, this chapter will outline which sectors both the government of Canada and governments across Asia have emphasized in their recoveries – hint green and tech are key pillars of many economic recovery packages.

In the past, FDI flows have decreased significantly during and immediately after an economic recession.[7] But evidence shows that inbound FDI plays a vital role in helping an economy recover post-recession. For example, in the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, an influx of FDI helped stabilize the financial tailspin.[8] In fact, after most economic crises, FDI has been shown to boost economic resilience by providing employment income, increasing competition, and lowering consumer prices.[9]

FDI in 2020: looking up from the bottom of the hole

2020 was a devastating year for FDI both in Canada and across most of the globe. In Canada, Q2 of 2020 saw an overall 46.9 per cent decrease in inbound FDI flows compared to Q2 of 2019.[10] However, in Canada’s case, the direction of FDI flows matters – looking at Canada’s investment relationship with the Asia Pacific region, while inbound FDI decreased significantly, falling from C$9B in 2019 to $6.4 billion in 2020 (a 29 per cent decrease), outbound FDI actually increased from C$11.5B in 2019 to C$16.7B in 2020 (a 45 per cent increase).[11]

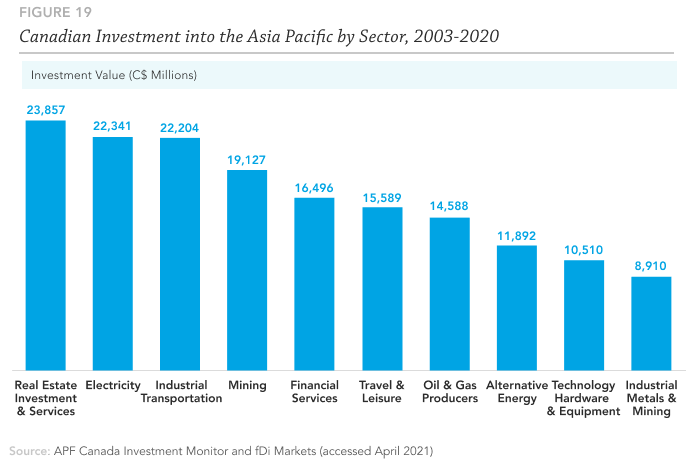

This increase in outbound FDI is partially due to some very substantial outbound deals that took place in 2020, such as Brookfield Asset Management’s acquisition of RMZ Corp in India for C$2.6B, the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System’s acquisition of Australia’s TransGrid for C$1.7B, and the British Columbia Investment Management Corporation’s acquisition of a telecom tower company in India for C$1.2B. In terms of sectors, electricity was the most lucrative, accounting for C$4.3B; real estate investment and services came in second with C$3.6B; and technology services and equipment came in third with C$2.3B.

Comparatively, inbound investments were simply smaller. The single largest inbound deal in 2020, ByteDance’s expansion into Canada, was valued at C$829M. The three most lucrative sectors were travel and leisure, coming in at C$2B; mining at C$900M; and media at C$830M.

Inbound FDI in recessions of yore

Defining a recession as occurring when there are two consecutive quarters of declining GDP, Canada has had two recessions in recent history: one in 2008-09 and one in 2015. Both of these recessions provide us with opportunities to understand how FDI into Canada has responded amid an economic decline.

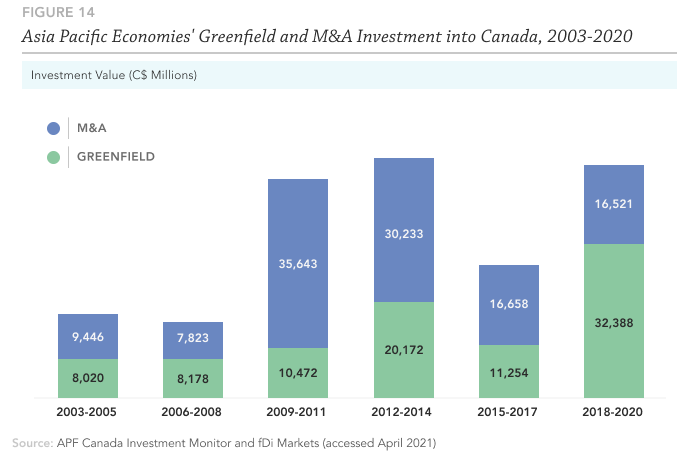

Both periods saw a decrease in FDI between Canada and the Asia Pacific during the recession’s onset and duration. However, immediately after the 2008-09 recession, inbound FDI from the Asia Pacific grew significantly, from C$8.2B in 2008 to C$17.2B in 2010 – an increase of over 50 per cent. And the 2015 technical recession exhibited roughly the same pattern – inbound FDI from the Asia Pacific grew significantly post-economic crisis, from C$5.7B in 2015 to C$11B in 2016.[12]

It is important to note that the impact of the COVID-19 recession on economic activity was uniquely severe. Accompanying the economic fallout, which occurred in part due to pandemic-related restrictions, have been financial safety nets unlike any we’ve seen in the past. So, while the recession will produce a significant opportunity to acquire distressed firms, government economic stimulus packages will also create resilience among firms that would otherwise have gone under months ago. Deal flow, particularly distressed deal flow, will be particularly impacted by this factor. Whereas in the 2008-09 crisis, we saw a large opportunity for distressed deal flow. While many firms are suffering greatly in this recession, others are receiving sufficient government stimulus and pivoting their businesses for success in the new post-COVID economy.

Outbound FDI – the resilient flow

While an increased inbound flow can contribute to Canada’s post-recession recovery, emerging evidence also points to the potential economic benefits of outbound FDI.[13] Considering that Canada’s outbound FDI is a) currently higher in value than our inbound FDI, with C$240B in investment value compared to the C$207B in inbound investment value and b) has increased in value during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is vital for Canada to understand the role outbound FDI is playing in its economic recovery and the strategic positioning outbound FDI plays in ensuring economic resiliency in a post-COVID economy.

UNESCAP has found that as companies begin to engage in outbound FDI, their activities produce returns that are transferred back to the home economy, such as higher export earnings, increased domestic output, increased productivity/ innovation, higher employment and wages, and overall economic growth.[14]

Specifically in the Canadian context, Export Development Canada (EDC) conducted a study on outbound FDI, and found both micro- and macro-level benefits – on a micro scale, outbound FDI results in benefits for the company itself such as lower costs, increased productivity and increased efficiency in supply chains. Based on a survey EDC conducted of Canadian companies with foreign affiliates, after investing abroad 95 per cent reported increased revenue, 92 per cent cited increased competitiveness, and 74 per cent reported an increase in overall productivity.[15] On a macro scale, EDC found that outward FDI can result in positive economic effects for Canada as a whole by creating employment opportunities and strengthening domestic businesses.[16]

However, much like inward FDI, it is important to recognize that there are differing degrees of economic benefits of outbound FDI, based on factors such as the income level or business environment of the home country, the size of the investing company, and where the outbound FDI is going.[17] That being said, the benefits outlined above are significant and should be taken advantage of, especially considering Canada’s already-strong outbound FDI.

Follow the Sector-Specific Growth

Looking at COVID-19 economic recovery plans across the Asia Pacific region, many Asian economies have chosen to implement green stimulus deals, focusing on clean tech, renewable energy and green finance, with the goal of creating a “green recovery.”[18] Examples include South Korea’s New Green Deal, New Zealand’s Focus on Environment and Jobs, and Indonesia’s National Economic Recovery Plan.[19] These plans have emphasized that a focus on environment is especially important considering the potential negative effects of the “double disaster” that is both climate change and COVID-19. A green recovery is crucial for any economy that wants to “build back better.”[20]

Other Asian economies – such as Singapore, Malaysia and China – have focused on digital stimulus packages, emphasizing digital innovations, IT and data.[21] This is largely because COVID-19 has demonstrated the importance of technology and digital infrastructure during times of crisis – and how digitization can help to build a more inclusive economic recovery.[22]

Looking at Canada’s economic recovery plan, the Industry Strategy Council has published a post-COVID-19 growth plan aimed at building a “digital, sustainable and innovative economy.”[23] The report focuses on four main pillars, including striving to become a “digital and data-driven economy,” being the “environmental, social and governance (ESG) world leader in resources, clean energy and clean technology” and to “build innovative and high-value manufacturing where we can lead globally.”[24]

The Industry Strategy Council focused on sustainability, innovation and digitization in its recovery plan for two main reasons: first, the Council believes that focusing on these sectors will help accelerate Canada’s recovery, as they are key factors of economic growth; and second, Canada was facing challenges pre-COVID in terms of digitization and innovation, and shifting to focus on these areas post-COVID will help place Canada in a leadership position on the world stage.[25]

There are clear intersections between the Canadian growth plan and those of many Asian economies, with mutual interests in digital, clean energy, and R&D. With that in mind, this intersection could translate into various bilateral investment opportunities. This report will focus on outbound opportunities specifically as those have proven to be resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic, and will most likely continue to be important for Canadian companies going forward. This chapter focuses on outbound investment in those high-growth sectors and attempts to outline potential opportunities for Canadian companies.

ECONOMIC RECOVERY PLANS IN SELECT ASIA PACIFIC ECONOMIES

This chapter will analyze four major economies’ COVID recovery strategies and how they may present investment opportunities for Canada. The economies covered in this chapter include South Korea, Singapore, Australia, and India. These economies are chosen for analysis not just because they have laid out an economic recovery strategy that aligns with Canada’s “digital, sustainable, and innovative” recovery, but these partners could also align with the Canadian government’s trade diversification objective.[26]

This does not imply that Canada’s investment opportunities in the region will exclusively be in these markets, as other major economies, such as China and Japan, are likely to remain critical partners to Canada’s economic recovery. Rather, these four economies have the potential to elevate their existing investment relations with Canada in the post-COVID environment.

For the purposes of this report, APF Canada Investment Monitor combines the various sub-sectors in the modified industry classification benchmark (modified ICB) when identifying digital and clean energy investments. Below are the operational sectoral definitions:

- Digital industry includes companies engaged in computer services, internet, software, computer hardware, semiconductors, and telecommunication equipment.

- Clean energy industry includes renewable energy equipment manufacturers, alternative fuels developers and producers, and alternative electricity companies.

While these definitions may not holistically capture the digital and clean energy industries, narrow definitions allow us to focus on the key enablers in these industries as well as reduce the number of false-positive transactions.

APF Canada Investment Monitor also adopts the OECD’s 2015 Fracasti Manual concepts and definitions (which Statistics Canada also employs) when identifying R&D-related investments. Accordingly, “R&D comprise creative and systematic work undertaken in order to increase the stock of knowledge – including knowledge of humankind, culture and society – and to devise new applications of available knowledge.”[27]

While this definition would also encompass work undertaken in the social sciences, humanities, and arts, given the sectoral focus of this report, we only capture investments associated with R&D activities in the natural sciences, engineering and technology, the medical and health sciences, and agricultural and veterinary sciences.[28] See methodology and data sources chapter on how APF Canada Investment Monitor identifies investments associated with R&D.

KOREA'S NEW DEAL: TRANSITIONING TOWARDS A SUSTAINABLE AND DIGITALIZED ECONOMY

South Korea announced C$128.5B (KRW$114.1T) worth of government recovery programming as part of a plan termed the ‘Korean New Deal’ (KND) in July 2020. The KND is part of the South Korean government’s plan to accelerate South Korea’s transition towards an inclusive, green, and digital economy. According to President Moon Jae-In, the KND will transform South Korea from a “fast follower” into a “leading” economy.[29] To achieve this vision, the Korean New Deal is structured in three major pillars: the Digital New Deal, Green New Deal, and Stronger Safety Nets. Underneath these pillars, KND lays out nine focus areas and 28 specific projects to be implemented by 2025. Taken together, the Korean government hopes to generate more than 1.9 million jobs through KND programming.[30]

With C$97B (KRW$87.5T) in funding, digital and green account for most of the KND programming. On digital, the focus is on a more robust integration of data, network and artificial intelligence (DNA) throughout the Korean economy. Specifically, the government pledged to invest C$7.1B (KRW$6.4T) to develop a “data dam” that would enable and facilitate the collection, disclosure, and utilization of data throughout the economy.[31] To further reinforce Korea’s digital advantage, the government is investing C$16.4B (KRW$14.8T) to expand the integration of 5G and AI in the private sector through initiatives such as providing AI solution vouchers to SMEs.

The Green New Deal is another significant component of the KND. With C$48B (KRW$42.7T) in pledged investments, the South Korean government seeks to transition its economy towards carbon neutrality by 2050.[32] The Green New Deal promises to invest in greening Korea’s public infrastructures and expanding the use of sustainable and renewable energy throughout the economy. For instance, in one project, the government pledges to provide support for installing renewable energy equipment in 200,000 households.[33]

Lastly, the KND also lays out various programs across the three pillars to improve the economy’s R&D capabilities. In the digital realm, the South Korean government promises to support research and development in delivery systems which utilize robotics, internet of things (IoT), and big data. KND also strives to leapfrog South Korea’s research capacity in clean technologies. For instance, in one program, KND pledges to support the development of hydrogen technologies. KND further reinforces these R&D programs by committing C$1.2B (KRW$1.1T) to train 100,000 digital and 20,000 green talents by 2025.[34]

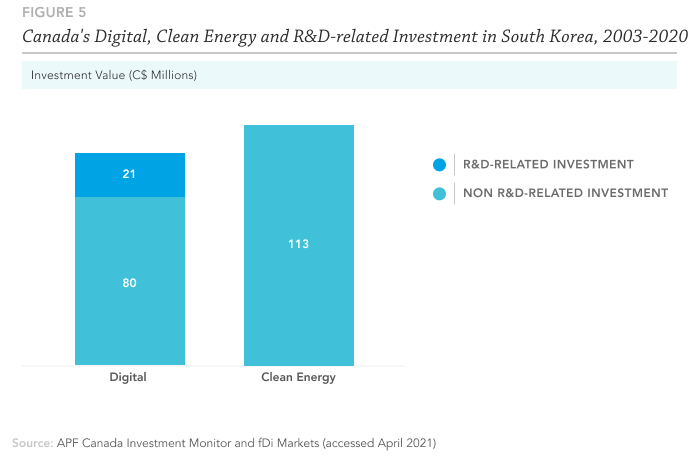

While KND could present substantial opportunities to Canadian digital, renewable, and R&D sectors, Canadian outbound investments to Korea remain limited in these high-growth sectors. From 2003 to 2020, Canadian companies have invested C$5B into South Korea via 53 deals. Of the C$5B worth of Canadian investment in South Korea, the digital and clean energy sector only accounted for C$101M and C$113M, respectively. One notable transaction came in 2020 when NexOptic Technology Corp., a Vancouver-based artificial intelligence company, opened a new office in Seoul. In the clean energy realm, Kolon Hydrogenics, a joint venture between Kolon Water & Energy and the Mississauga-based Hydrogenics Corporation, invested C$113M to develop a 1-megawatt fuel cell power system in Seosan, a city located southwest of Seoul.

The APF Canada Investment Monitor also identified four Canadian R&D-related investments in South Korea amounting to C$21M. However, all identified R&D investments are in the digital sector. One notable transaction came in 2018 when the Montreal-based artificial intelligence firm Element AI invested an estimated C$2M to open a new office in Seoul. Element AI’s 2018 investment was associated with a research collaboration agreement with Shinhan Financial Group to incorporate AI forecasting technology in its investment advisory platform.[35]

Potential Barriers for Entering the South Korea Market

While the KND could incentivize more significant Canadian investment to South Korea in the digital, clean energy, and R&D sectors, there remains potential barriers for Canadian companies to take advantage of KND-induced activities. Analysts have noted that KND’s primary objective is to leapfrog South Korea’s own domestic industries and to allow foreign participation may defeat such an objective.[36] In particular, some Korean firms are concerned that allowing foreign companies, which are perceived to be technologically superior, to bid for KND opportunities will threaten domestic players’ opportunity to take advantage of the stimulus package. Given KND’s policy objective and the potential public opposition to foreign participation, the South Korean government may favour domestic companies over foreign bidders in KND programs, impeding Canadian investment opportunities.

Furthermore, skepticism over foreign investment could heighten depending on the method of entry. According to a 2019 study by the Pew Research Center, while most South Korean respondents welcomed foreign greenfield investments, 71 per cent had a negative perception of foreign companies’ acquisition of Korean firms.[37] The public’s negative view of foreign purchases of Korean firms could pressure the Korean government to strengthen its regulations around foreign acquisitions, particularly in sectors that see a high level of government investment.

In fact, South Korea has been introducing more stringent measures to safeguard its own technological advantage and national security. Like many advanced economies, South Korean policymakers have been concerned about the leak of core technologies, which may undermine economic competitiveness and national security. While such concern predates the pandemic, policymakers may introduce more measures to safeguard emerging technologies in the digital and green sectors, which are expected to set the course for South Korea’s economic recovery. According to UNCTAD’s Investment Policy Monitor, South Korea recently amended the Enforcement Decree of the Foreign Investment Promotion Act in August 2020.[38] The amendment enables officials to request a review of foreign investments where there is a strong likelihood of leakage of core national technologies. These measures may add regulatory risks, or at least compliance cost, for Canadian companies intending to invest in KND-associated high-growth sectors.

AUSTRALIA'S 2020-21 BUDGET AND RECOVERY PLAN

Australia released its 2020-2021 Budget in October 2020, which consists of C$92.2B (AUD$98B) for response and recovery support – of that, C$23.5B (AUD$25B) is the COVID-19 Response Package, and C$69.6B (AUD$74B) is the JobMaker Plan. The budget is largely focused on increasing incomes for households and businesses, boosting manufacturing and infrastructure investment, and decreasing the unemployment rate by creating jobs.[39] The plan involves a variety of different sectors and priorities, but of particular interest for this report is the recovery plan’s actions on R&D, clean energy and digitization.

First, Australia’s recovery plan committed an additional C$1.9B (AUD$2B) over the next four years to its pre-existing Research and Development Tax Incentive. The R&D tax incentive is meant to encourage businesses to conduct R&D activities, by offsetting the cost. There are two main parts of this tax incentive: a 43.5 per cent refundable tax offset for eligible entities with aggregated turnovers of less than C$18.8M (AUD$20M) per year; and a 38.5 per cent non-refundable tax offset for any other eligible entity.[40] Canadian entities can be eligible for this tax benefit if they set up: a permanent establishment in Australia; an Australian resident company; a corporation that is an Australian resident for tax purposes.[41] The Australian government has stated that it focused on R&D because it drives technological innovation, which in turn leads to increased productivity and increased economic growth.

The budget also includes the government’s Digital Business Plan. The plan emphasizes that COVID-19 has sped up the adoption of digital technologies by both Australian businesses and consumers, showcasing the growing importance of prioritizing digitalization going forward. The Digital Business plan involves a C$764M (AUD$800M) investment “to enable businesses to take advantage of digital technologies to grow their businesses and create jobs as part of our economic recovery plan.”[42] For example, the plan includes a C$27.9M (AUD$29.2M) investment in the rollout of 5G; C$21.2M (AUD$22.2M) to expand the Australian Small Business Advisory Service, which includes the Digital Solutions program, the Digital Directors Training Package and the Digital Readiness Assessment; and C$9.1M (AUD$9.6M) for fintech companies to export financial services and attract inbound FDI.[43] According to the plan, a focus on digital transformation will create jobs and increase productivity.

Finally, the government has also focused on clean energies. The recovery plan includes an investment in new energy technologies, with the intention to create jobs and boost economic growth. The investment is C$1.81B (AUD$1.9B) to lower emissions and improve the sustainability of Australia’s energy supply. The investment includes C$47.7M (AUD$50M) towards the Carbon Capture Use and Storage Development Fund, C$67.1M (AUD$70.2M) toward a hydrogen export hub, and C$64M (AUD$67M) toward microgrids to deliver sustainable and reliable power to remote communities. There will also be an additional C$1.54B (AUD$1.62B) made available for the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) to invest in new technologies that lower emissions.

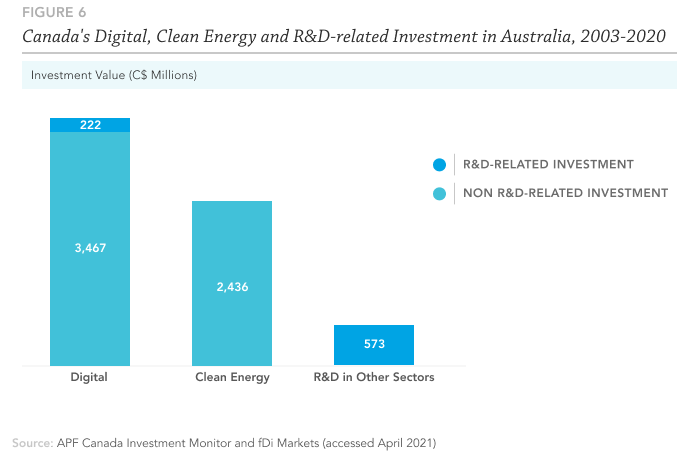

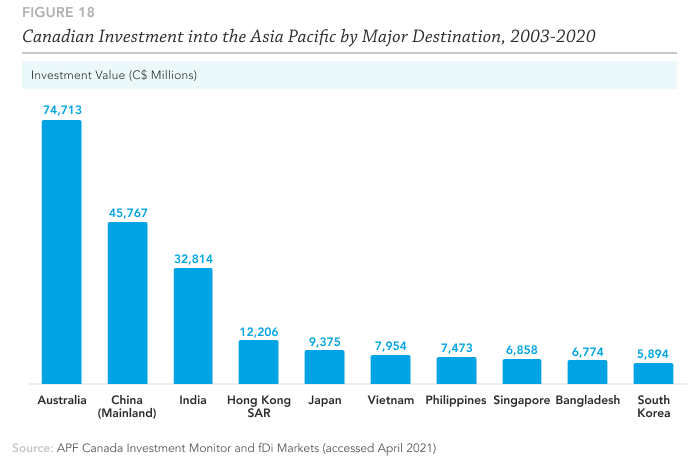

According to APF’s Investment Monitor, Australia is the largest destination in the Asia Pacific region for Canadian investors – from 2003 to 2020, Canadian investment in Australia totalled C$74.7B. With this, the Australian government’s focus and investment in the areas of R&D, clean energy and digitization can provide significant opportunities for Canadian companies, especially considering Canada’s own focus on those sectors post-COVID-19.

The digital sector is among the top sectors for Canadian investors in Australia, with C$1.3B invested in software and computer services, and C$2.4B invested in technology hardware and equipment from 2003 to 2020, totalling C$3.7B. The Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan board accounts for the majority of those investments in terms of value, having invested C$2.2B in Australia’s digital sector since 2003. Their largest deal occurred in 2013, when the board acquired 70 per cent of three Australian telecommunications companies – Nextgen Networks, Metronode and Infoplex – from Australia-based Leighton Holdings Limited. The acquisition was valued at C$1.05B.

Turning to clean energy, there were 16 Canadian outbound deals to Australia from 2003 to 2020, totalling C$2.4B. Of those deals, 12 were in alternative electricity, totalling C$2.4B, and four were in alternative energy, totalling C$49.3M. Canadian Solar Inc has been especially active in this sector, having conducted seven deals between 2003 and 2020 totalling C$1.2B. The majority of these investments occurred in 2018, when Canadian Solar purchased five large solar power projects in New South Wales. Another recent notable deal is McCain’s investment of C$345M, to add an 8.2-megawatt biogas energy facility to its site in Ballarat, Australia. The project will utilize a combination of solar and co-generation technology, and the electricity produced will supply the company’s food processing plant. The new system is expected to reduce the facility’s overall energy consumption by 39 per cent.[44]

Finally, other sectors in Australia also saw Canadian R&D-associated investments. APF’s Investment Monitor identified 16 Canadian R&D-related investments into Australia, totalling C$795M. The majority of deals were in in the pharmaceuticals sector (seven deals). Recent notable deals include Cronos Group’s subsidiary Cronos Australia opening a research and development centre in 2019 in Victoria, Australia, with a C$30.6M investment. Cronos Australia is a medicinal cannabis company, and the establishment of this R&D centre is expected to create approximately 120 new jobs.

Barriers to Investment?

Despite the opportunities these sectors can provide for Canadian companies, there are still barriers to investing in Australia. In March 2020, the government introduced temporary measures which required that all foreign investment into Australia be approved by the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB), regardless of the amount, sector or investor.[45] This new screening also meant that FIRB could take up to six months to approve an FDI proposal – compared with the 30 days it took before these new measures.

In December 2020, some of these regulations became permanent, coming into effect as of January 2021. Australia’s Parliament reformed the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeover Act of 1975, now requiring all foreign investors to have approval for any investment “that is sensitive to national security, regardless of value.”[46] They also hold that investors can be subject to “enhanced monitoring and investigation powers, as well as stronger and more flexible enforcement options and penalties,” and must also “continue bearing the costs of administering the foreign investment regime.”[47] It is expected that these new security-based regulations will most strongly affect telecommunication, energy and utilities investments, and some technology, services and infrastructure investments.[48] These new screening measures could be a deterrent for certain Canadian companies, due to time constraints and potential additional costs.

There are also domestic political pushbacks. The Lowy Institute Poll in 2019 found that 39 per cent of Australians believe that foreign investment in Australia is a “critical threat,” and 51 per cent of Australians believe that it is “an important but not critical threat.”[49] The Australian public seems to be especially against investments in Australia’s agricultural sector.[50] Another Lowy Institute poll conducted in 2016 found that 63 per cent of respondents were strongly against the Australian government allowing foreign companies to buy Australian farmland.[51] Negative perception over foreign investment could also pose regulatory uncertainty to Canadian companies intending to invest in Australia.

ASEAN AND SINGAPORE: A REGIONALLY CONNECTED RECOVERY

If ASEAN were one economy, it would be the sixth-largest in the world, and one of the fastest growing.[52] The regional intergovernmental organization and trading bloc comprises Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. As was the case in the 2008-09 recession, ASEAN is projected to make another impressive recovery going into 2021, with real GDP forecasted to rise by six per cent.[53] The resumption of growth is in one part fueled by the economic recovery spending and rollout of vaccines by member nations, and in another by their regional integration, coordination and sectoral strengths. In November, ASEAN put forward the ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework (ACRF), which focuses on accelerating digital transformation and achieving sustainability.[54]

For its part, Canada has been eyeing a free trade agreement with ASEAN for years, having published a joint-feasibility study to assess the possibility.[55] Furthermore, as ASEAN deepens its engagement with Australia, China, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand through RCEP’s recent entry into force, seizing opportunities will be of particular importance for securing competitive advantages in the region.

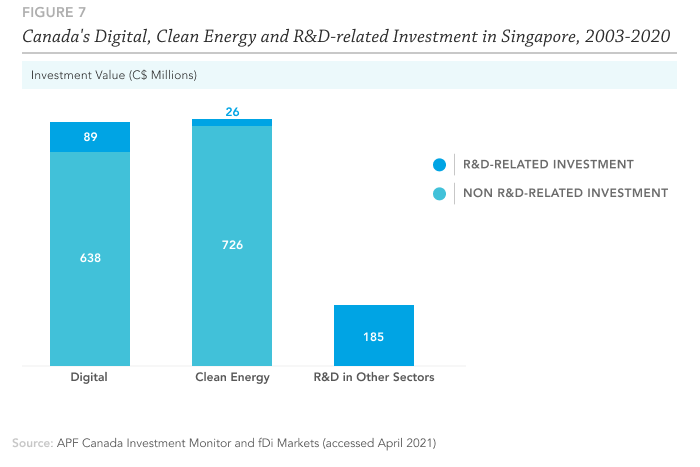

Canada’s current outbound investment flow to ASEAN is led by Vietnam, the Philippines and Singapore, respectively, accounting for over 65 per cent of investment into the bloc. But in the digital, clean energy and R&D sectors, Singapore dominates in all categories. This section thus focuses on opportunities and risks in Singapore’s recovery plan and how the city-state can be used as a bridge to ASEAN’s market.

Singapore’s Budget 2021: ‘Emerging Together Stronger’

The 2021 “Emerging Together Stronger” budget announced over C$95B in stimulus and support spending. Half of the budget is allocated to social development and special transfer expenditures, primarily focused on supporting businesses, workers and jobseekers during the crisis.[56] Another 26 per cent is earmarked for economic development, with the focus on moving from “containment to restructuring” to equip “businesses and workers with deep and future-ready capabilities.”[57] In this aspect, the government is seeking to support transformation by “helping [businesses] digitalize, adopt new technology, innovate, collaborate and gain access to global markets.”[58] Finally, Budget 2021 unveiled Singapore’s Green Plan 2030. Accordingly, Budget 2021 includes a variety of measures around the digital, clean energy and R&D sectors.

Budget 2021 leverages a variety of “capital tools to co-fund transformation,” with the primary focus on digital transformation.[59] The new Emerging Technology Programme co-funds the costs of trials and adoption of next-frontier technologies like 5G, AI and trust technologies.[60] With COVID-19 having accelerated the digitization wave worldwide, the programme is designed to speed up the commercialization of digital innovation, proactively setting Singaporean businesses up to seize up on global investment opportunities as they arise.[61] This is just one of many programs aiming to speed digital transformation through either co-funding or connecting businesses with strategic advice from consultancies, such as the new CTO-as-Service program for SMEs and the Digital Leaders programme. With digitization as a top priority, opportunity is ripe for Canadian companies looking to tap into the market.

Digitization is likewise emphasized as a priority area within the government’s new innovation and R&D measures, which aim to establish Singapore as “Asia’s Silicone Valley.”[62] Singapore’s Open Innovation Platform, established in 2018, matches “problem solvers” (innovative companies) with “problem owners” (sector agencies and Trade Associations and Chambers), co-funding the prototyping and deployment of solutions.[63] Another big-ticket-item is the enhancement of the Global Innovation Alliance (GIA). GIA connects businesses with global innovation hubs for co-innovation and market expansion. The programme co-funds the costs up to 70 per cent and Budget 2021 promises to expand the network of overseas partners, which could unlock opportunities for engagement with Canadian firms.

Finally, with Green Plan 2030, Singapore has joined the ranks of many other Asia Pacific economies aiming for a “green recovery.”[64] The first goal under the Energy Reset pillar of the plan is to phase out internal combustion vehicles and switch to cleaner energy vehicles by 2040.[65] Toward this end, the government has earmarked C$28 million over the next five years and introduced a host of incentives to encourage the transition.[66] The Energy Reset also aims to increase the use of solar energy fivefold by 2030.[67] To achieve its solar targets, the plan intends to tap into clean energy sources from ASEAN and globally by upping electricity imports.[68] Lastly, the government has announced $19B of public sector green bonds, which it projects will catalyze “green issuers, capital, and investors to (its) financial centre.”[69]

An overarching principle of the budget, particularly around the business measures, is internationalization. A Double Tax Deduction for Internationalization allows Singaporean businesses a 200 per cent tax deduction on market expansion and investment development expenses, of up to C$142,000 (S$150,000). Furthermore, Heng announced in his budget speech that Singapore would continue to work with ASEAN partners on sustainability and digitization through the ASEAN Smart Cities Network and the Southeast Asia Manufacturing Alliance, with the goal of the latter being to “promote a network of industrial parks to manufacturers who are looking to invest in Singapore and the region.”[70]

Since 2003, Singapore has been the eighth-largest recipient of Canadian outbound FDI in the Asia Pacific, with C$6.9B invested through 109 deals. Among ASEAN economies, Singapore is the third-largest recipient of Canadian FDI, following Vietnam and the Philippines. But turning to the digital, clean energy and R&D sectors, Singapore ranks first in outbound investment value among all ASEAN economies. These sectors together represent 24 per cent of Canada’s FDI investments into Singapore. Budget 2021 presents opportunities to further strengthen investment relations with Singapore in these high-growth sectors.

Collectively, Canadian companies have invested C$727M into Singapore’s digital sectors through 37 deals since 2003. In 2020, APF Canada’s Investment Monitor recorded its largest ever Canadian investment in Singapore’s digital sector. Ontario Teacher’s Pension Plan (OTPP) made a C$300M greenfield investment in Princeton Digital Group, one of Asia’s leading data centre companies. In the clean energy sector, there have only been three outbound deals recorded since 2003, but these represent C$752M in value. The largest deal was once again made by OTPP in 2020 through a C$545M greenfield investment in Equis Development Pte Ltd (EDL). EDL develops and operates renewable energy infrastructure in Australia, Japan and South Korea.[71] Ben Chan, OTPP regional managing director for the Asia-Pacific, said, “We see data centres as a compelling investment opportunity given their essential role in the rapid digitalization and growth of data occurring in Asia and around the world.”[72]

APF Canada also identified seven R&D outbound investments, totalling C$300M. A recent notable deal was Hydro Quebec’s C$46M investment in the opening of a laboratory focused on developing new nanomaterials and nanotechnologies for electric vehicles. This supports Green Plan 2030’s target of transitioning to cleaner energy in transportation. The lab was opened jointly with the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), another government initiative that has been enhanced under Budget 2021. Through the A*STAR Partner Centre at Suzhou Industrial Park, companies can draw on the expertise and advanced facilities of A*STAR before getting their products ready for entry into the Chinese market.[73] This program could provide a launching pad for other Canadian companies looking to do the same.

For its part, the Canadian government has taken notice of the potential and has set up the Southeast Asia Cleantech Canadian Technology Accelerator. The program offers Canadian companies potential investment, partnerships and guidance to enter the markets of Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines.[74] Further, with Canada’s entry into CPTPP alongside Singapore, Canadian companies investing in Singapore will enjoy competitive advantages against non-members. While CPTPP includes four of 10 ASEAN members (Singapore, Brunei, Malaysia and Vietnam), investing into Singapore can provide Canadian companies with export access to the whole of ASEAN.

Soft Barriers to Investment

Singapore enjoys a strong international business reputation, ranking second among 190 economies for ease of doing business by the World Bank.[75] However, investors should be aware of potential barriers to investment as well. On the human capital front, the government has introduced measures to partially subsidize the cost of recruiting Singaporean workers, to reduce the ratio of Singaporean to foreign workers.[76] Another potential barrier is that of competition with monopolies of government-related enterprises in sectors such as financial services, professional services, media, and telecommunications.[77] Furthermore, in terms of regional reach, companies looking to set up headquarters in Singapore with the goal of establishing subsidiaries in ASEAN nations may face a degree of regional uncertainty in their investments due to ongoing political turmoil in Thailand and Myanmar.

INDIA'S RECOVERY PLANS: DEVELOPING ECONOMIC SELF-RELIANCE

In February 2021, Indian Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the allocation of C$95.5B (Rs5,540 crore) for the 2021-2022 fiscal year to achieve the government’s goal of a “self-reliant” India and support the country’s economic recovery.78 The push for self-reliance is evidenced by the budget’s focus on domestic growth. Sitharaman’s budget speech emphasized skill development, education, and infrastructure projects as the main paths to achieving self-reliance. Overall, the budget is divided into six major pillars: health and wellbeing, physical and financial capital and infrastructure, inclusive development, reinvigorating human capital, innovation, and R&D, and lastly, minimum government and maximum governance. The focus of this report will be the pillars related to R&D, clean energy, and digitization initiatives.

The Union Budget 2021 plans to facilitate innovation and R&D through the establishment of a National Research Foundation (NRF). C$8.6B (Rs50,000 crore) has been allocated for the creation of the NRF over the course of the next five years. The aim of this “Glue Grant” is to promote cross-institution collaboration that will spur innovation and R&D. The current plans suggest that the NRF will be a formal institution used to connect and strengthen research institutions across nine major cities. The NRF will also encourage projects that are focused on areas that the government considers a priority.

The Indian government recognizes the importance of the renewable energy sector and has pledged C$172M (Rs1,000 crore) to the Solar Energy Corporation of India and an additional C$259M (Rs1,500 crore) to the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency. In the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, India agreed that by 2030 it would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 33 per cent. A large-scale movement towards reliance on renewable energy would significantly increase India’s ability to meet this goal. The finance minister also announced that the National Hydrogen Energy Mission would be launched in the coming year, focused on developing green hydrogen energy, and the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy was allotted C$4.3M (Rs25 crore) to encourage the research and development of hydrogen technologies.

Finally, the budget identified two initiatives that will further India’s digitalization process. The first is an allocation of C$259M (Rs1,500 crore) for the promotion of digital payments using financial incentives. In addition, the government plans to support fintech start-ups and provide them with access to a global market by establishing a fintech hub in Gandhinagar Gujarat International Finance Tec (GIFT) City, India’s first smart city. The hub is also expected to create up to 150,000 jobs and spur R&D and innovation in the fintech field.[79]

While the Indian government is focused on increasing the country’s self-reliance in 2021, the R&D, digital, and renewable energy sectors could provide opportunities for Canadian investors. India is already a popular destination for Canadian investment. Since 2003, investment in India has reached a total of C$32.8B, through 260 transactions. This makes it the third largest recipient of Canadian FDI, after Australia and China.

Investment Monitor data suggests that the clean energy and digital industries are already sought after by Canadians, as the telecommunications and alternative electricity sectors are both in the top five sectors for Canadian investment. In total, the clean energy and digital industries have received C$2.2B and C$3.5B, respectively. Of the C$2.2B invested in India’s clean energy sector, C$1.9B has been invested in alternative electricity, and C$277M was invested in renewable energy equipment. Toronto-based SkyPower Global, a solar power development company, is responsible for the majority of the investment in alternative electricity, having invested C$848M to build and operate 200-megawatt solar energy projects in Telangana through two transactions, one in 2015 and the other in 2016.

Investments in the digital sector are more diverse, spanning the computer services, semiconductor, software, and telecommunications equipment industries. In the software sector C$800M was invested through 39 transactions, the largest number of deals for any sector related to digital technology. However, the telecommunications equipment industry has received the largest total investment value, with C$2.5B invested between 2003 and 2020. The largest outward investment in India’s telecommunications sector was the C$2B acquisition of a telecommunications tower company by British Columbia Investment Management Corporation and Brookfield Infrastructure Partners. This transaction occurred in 2020, although there has been a fairly equal distribution of deals across all years since 2003.

Outside of the digital and clean energy industries, other sectors have also received R&D-related investments. C$561M worth of Canadian investments into India could be associated with R&D activities between 2003 and 2020, through 18 transactions. These investments are largely concentrated in the biotechnology and pharmaceuticals sectors, with over C$157M invested in these two sectors via four deals. One notable transaction is a 2018 R&D-associated investment in the health-care sector. The Canadian pharmaceutical company Jamp Pharma Corporation invested C$46M to establish its biggest centre of excellence for R&D and manufacturing drugs in Hyderabad. The project is expected to create 2,000 jobs once the centre has been completed.[80]

Potential Barriers to Investment

India’s COVID-19 recovery plan could provide Canadians with more opportunities to invest, as the government plans to expand the fintech sector and give tech start-ups access to the global market through the establishment of a fintech hub. However, the emphasis in the budget on “self-reliance” might present a barrier to investment in industries that India wants to further develop domestically.

One example of this type of barrier is the Indian government’s decision to support the domestic production of solar panels and solar cells by increasing the duties on solar inverters and solar lanterns from the current 5 per cent to 20 per cent and 15 per cent, respectively. This will likely affect exports more than investment, though the general trend towards “self-reliance” may have a negative impact on India’s ability to integrate into global value chains.[81] The increase in emphasis on buying local could be concerning for foreign companies. This could have adverse effects on the investment environment, such as increased restrictions on market access.[82]

In addition, the results of recent polls suggest that the attitudes of Indians towards foreign investment have cooled in the last few years. A 2020 report by the Pew Research Centre found that there was a 13 percentage points decrease in support for the acquisition of domestic companies by foreign entities from 2014 to 2019.[83] The most recent data revealed that in 2019, 47 per cent of respondents said that they were opposed to foreign acquisitions.[84] While attitudes towards greenfield investments are more positive, the negative attitudes towards foreign acquisitions may pressure the government to further regulate the sale of domestic companies to foreign entities.

The long-term ripple effects of R&D investment become of elevated importance during recessionary periods. Looking back to the 2008 recession, Booz & Company’s (today Strategy& of PwC) “Global Innovation 1000” survey of the heaviest R&D spenders showed that over 90 per cent of company executive respondents saw that innovation spending was critical to growth for the upturn.[85] Accordingly, the Industry Strategy Council’s recovery plan emphasizes the need to support private investment in R&D and attract key global investments in Canada’s “areas of strength.”[86]

Asia Pacific economies too have put R&D on their recovery agendas, and FDI cross-engagement could prove mutually beneficial. APF Canada has recorded C$5B of R&D-associated investments from the Asia Pacific region since 2003. Canada’s top four Asia-Pacific sources of R&D-associated investments are Japan (C$2B), China (C$1.4B), South Korea (C$707M) and India (C$477M). Together, these account for 90 per cent of all inbound R&D-associated investments.

Sectorally, Asia Pacific partners have cumulatively invested the most in biotechnology (C$1.4B), technology and hardware equipment (C$1.2B), pharmaceuticals (C$924M), software and computer services (C$842M), and aerospace and defence (C$204M). And in the last three years, alternative energy has joined the pack, outplacing pharmaceuticals. These sectors are well-aligned with those “areas of strength” identified by the Industry Strategy Council.

Biotechnology is a sector identified by the Council as ripe for growth. Even before the pandemic, Canada’s biotech sector was booming with investment, and as a result of that momentum many Canadian biotechs have been at the forefront of COVID-19 therapeutics and vaccine development efforts.[87] The largest R&D-associated biotechnology Asia Pacific investment came from Japan in 2016. Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Osaka-based Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., acquired Toronto-based Cynapsus Therapeutics for C$900M, a specialty biotech company developing a drug to treat the motor symptoms of late-stage Parkinson’s disease.[88]

Another key sector identified by the Council is aerospace, which was hard-hit by the pandemic, but in which Canada has stood as a top five global leader.[89] The aerospace sector injects innovation into the Canadian economy, with R&D intensity that is five times higher than the rest of the manufacturing sector.[90] The sector is increasingly prioritizing decarbonization efforts, which require significant R&D to develop cutting-edge green technology and systems engineering. Promoting the sector’s innovation efforts could have multiplier effects for the digital and clean energy aspects of Canada’s economic recovery and help drive investment.

Japan, again, dominated the R&D-related investment in the aerospace sector with Mitsubishi Aircraft Corporation’s 2019 C$204M greenfield establishment of a SpaceJet Center in Montreal to carry out engineering, development, and product certification.[90] Key pull factors for Mitsubishi include the presence of a skilled workforce and a healthy innovation system. Canada’s workforce is one of the most highly educated in the world. Nearly two-thirds of adults have post-secondary education, which is 16 per cent above the OECD average.[91] The company’s chief development officer stated, “Quebec is the hub for some of the most sophisticated and advanced talent in the aerospace industry.”[92]

The government also offers programs and incentives to spur R&D spending. The largest is the scientific research and experimental development tax incentive, which provides over C$3B in credits and deductions annually. However, the Industry Strategy Council identified a lack of growth capital and commercialization incentives as pain points for Canadian sectors and recommended easing access to R&D incentives to attract FDI.[93]

Canada's National Picture

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS:

- 2020 marks the second consecutive year of decrease in the value of inward FDI, from C$9B in 2019 to C$6.4B in 2020. However, the number of transactions has increased since 2019, from 164 to 181.

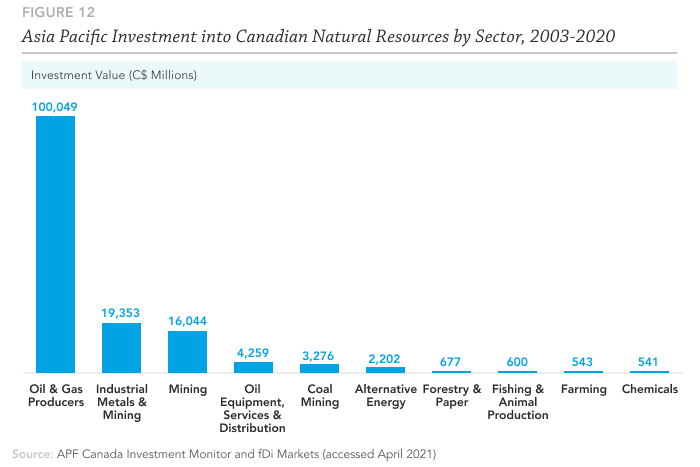

- The natural resources sector continues to receive the majority of the investment flow. In 2020, the mining industry was the largest recipient of FDI with C$1.1B invested through 13 deals, though the oil and gas sector has received the most investment overall.

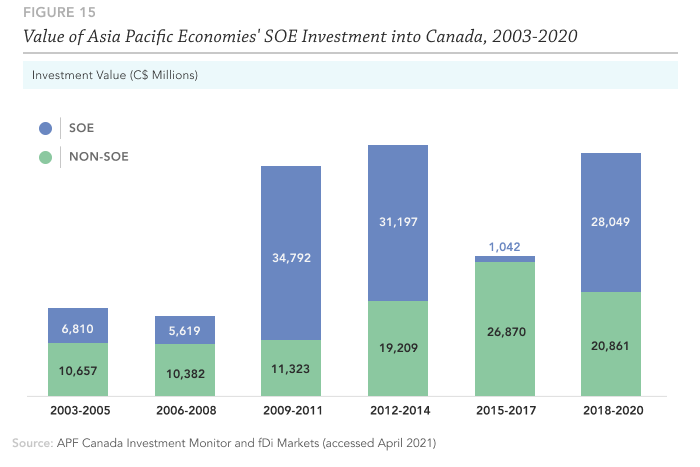

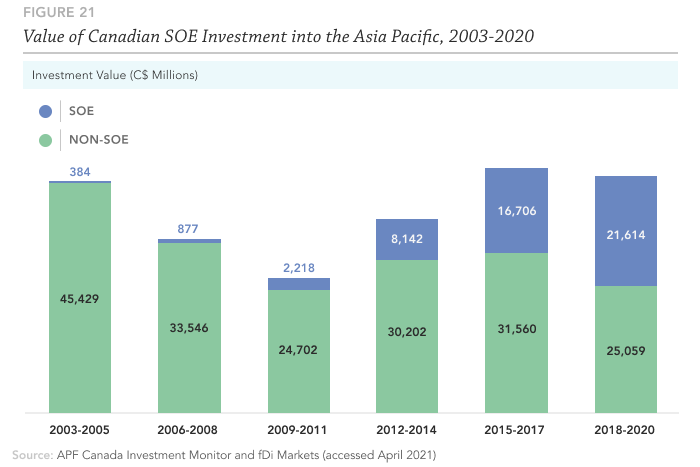

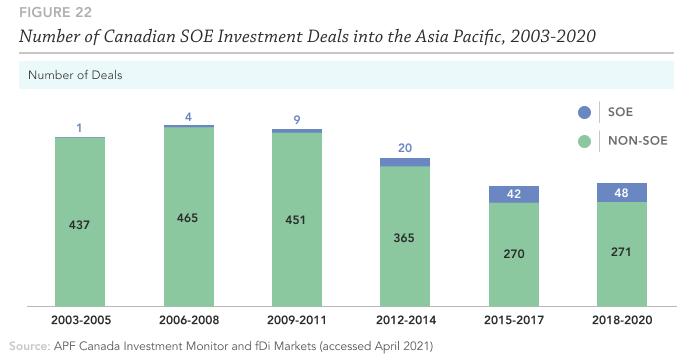

- State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) emerged as the largest contributors of inward FDI. The cumulative investment from Asia Pacific SOEs between 2003 and 2020 totals C$107.5B.

- Australia, China, and India have been the overall top three destinations for Canadian investments since 2003, accounting for C$74.7B, C46B and C$32.8B of the outbound flow, respectively.

- The top three sectors for outbound investment in 2020 were electricity, with C$4.3B; real estate investment and services, with C$3.6B; and technology hardware and equipment, with C$2.3B.

DEAL ACTIVITIES CONTINUE TO REACH NEW HEIGHTS

The total value of Canadian inward foreign direct investment decreased in 2020, relative to 2019 levels, marking the second consecutive year of decrease in total FDI. In 2020, Canada received C$6.4B in investment, C$2.7B less than the total value of inbound investment in 2019. However, in 2020, the total number of deals increased by more than 11 per cent as compared with 2019 levels. The past year saw 180 transactions, setting a new annual record and continuing the trend of the number of deals increasing over time, which began in 2017.

The increase in deal count is also apparent when examining the most recent three-year period. As Figure 7 shows, between 2018 and 2020, the number of deals reached a record high with 476 transactions. During this period, Canada received C$48.9B in investment from Asia Pacific economies, a close second to the historic high of C$50.4B in inbound investment seen from 2012 to 2014. When compared with the previous three-year period, 2015 to 2017, the inbound investment value from 2018 to 2020 increased by C$20.9B, or 75 per cent.

APF Canada’s Investment Monitor has captured C$207B in inbound FDI through 1,441 deals from Asia Pacific economies since 2003. The majority of the investment flow has been generated in the past nine years, accounting for almost 61 per cent of total investment value. Over time however, the value of investment seems to share a less direct relationship with deal count. In the 2000s and early 2010s, the years that saw the most investment flows also had the largest number of deals. However, in the second half of the 2010s, a large number of deals did not necessarily generate a similarly large investment value. Between 2012 and 2014, the average amount invested per deal was C$202M, but this average has dropped to C$103M in the most recent three-year period. This demonstrates that the recent increase in deal count outpaces the increase in investment value, which in turn drives down the dollar invested per deal – decreasing the overall average.

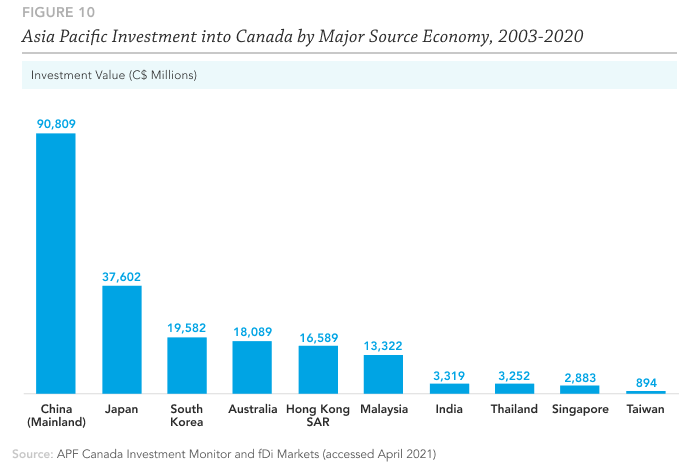

Asia Pacific investment in Canada continues to be highly concentrated with a select few source economies. China, Japan, South Korea, and Australia alone have accounted for 80 per cent of total inbound investment since 2003. China remains the top source of FDI investment in Canada, with C$90.8B through 407 deals since 2003. Japan comes in second with C$37.6B in investment and 320 deals, followed by South Korea with C$19.6B through 95 deals, and finally Australia with C$18B through 200 deals.

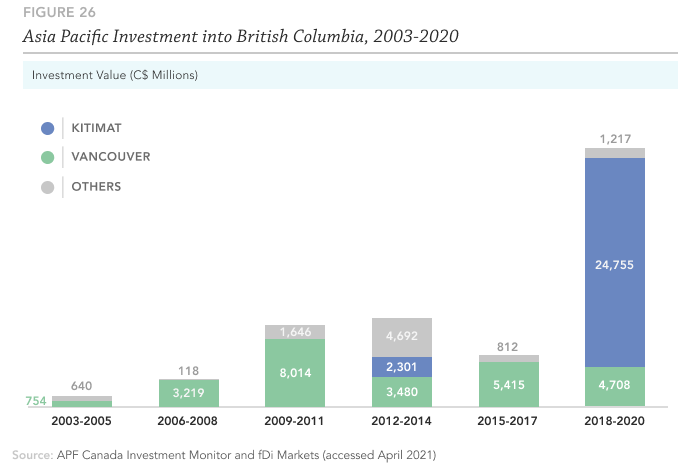

Although China has been an engine of investment in Canada, inbound investment flow has seen ups and downs throughout the years. For instance, Chinese inbound investment reached a high of C$29.6B in the 2012 to 2014 period, only to drop by 63 per cent in the following period to C$11B. Some of that loss was recovered in the 2018 to 2020 period, with C$15.8B invested. The growth, however, was in large part attributable to a C$6.2B Chinese joint-venture investment in the liquified natural gas (LNG) export facility at Kitimat in 2018.

Japan is Canada’s second-largest source of investment in the region. Inbound investment from Japan reached an all-time high in the three-year period of 2018 to 2020 at C$10B. Similar to China, the high investment value was fuelled by Japan’s C$6.2B joint-venture investment in the LNG project by Mitsubishi Corporation.

In the most recent three-year period, Australia recovered much of the lost investment flow from the 2015 to 2017 period, in which investment values fell dramatically from previous periods to just C$221M. In the 2018 to 2020 period, Australian investment recovered to C$3.4B, largely through deals in the mining sector in British Columbia, Ontario, and Nova Scotia.

Although Canada’s traditional economic partners continue to comprise a large share of inward investment, in recent years non-traditional partners have made significant investment footprints in Canada. In 2020 specifically, Singapore emerged as the top source of investment dollars with C$2.1B invested. This was largely fuelled by a series of investments from Parks Bottom Co Real Estate Holdings Inc., an indirectly wholly owned entity of the Singaporean GIC Private Ltd., in an assortment of luxury hotels across western Canada.

The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on economies around the world, as policy makers impose strict public health measures to save lives. With decreased global demand, disrupted supply chains, and a pessimistic market outlook, foreign direct investments have been expected to sharply decline this year.[94] Developed economies are among the hardest hit. The United Nations Conference of Trade and Development (UNCTAD) recently estimated that foreign direct investment flows to North America declined by 46 per cent in 2020.[95]

Canada, like many other economies, has been facing an uphill battle in FDI attraction from the Asia Pacific region. APF Canada’s Investment Monitor has captured C$6.4B worth of investment from the Asia Pacific economies in 2020. Compared to the previous year, investment flow from the Asia Pacific region has decreased by 29 per cent, or C$2.6B.

Source economies, such as China, Japan, and Australia, saw a significantly lower level of investment flow into Canada. For instance, Chinese investments into Canada dropped from C$4.1B in 2019 to C$1.5B in 2020, a 64 per cent drop, while Japanese investments into Canada saw a decrease of 38 per cent (C$488M).

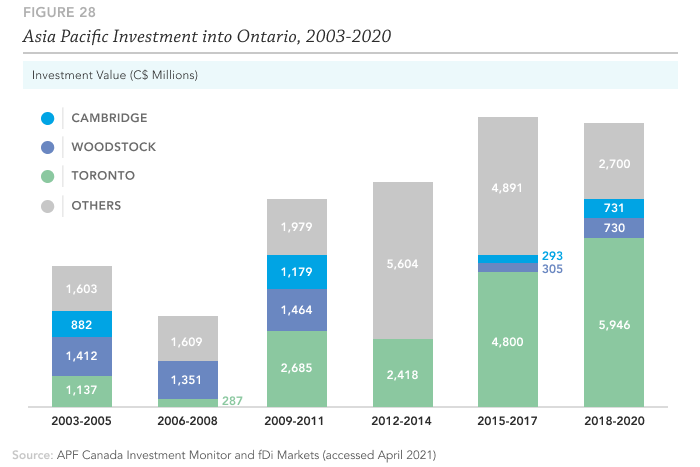

Looking back, inbound investments into Canada from the Asia Pacific have been comparatively resilient in past recessions. During the 2008 Financial Crisis, Asia Pacific companies channelled C$8.2B of investments into Canada, a 76 per cent growth from C$4.6B in the previous year. One of the biggest Asia Pacific investments recorded that year came when Chinese refiner Sinopec International Petroleum Exploration and Production Corp acquired Tanganyika Oil Co. for C$2B. Another big-ticket investment came when Toyota Motor invested C$1B in an auto assembly plant in Woodstock, Ontario.

Even in the 2015 technical recession when Canada saw investments from the Asia Pacific region decline by 52 per cent year-on-year with only C$5.7B, a sharp rebound quickly ensued in the following year. In 2016, Asia Pacific companies channeled C$11.1B of investments, just C$861M short of the 2014 level. The rebound was primarily driven by Chinese investments into Canada, which saw a C$4.3B jump in investment flow from 2015 to 2016.

The real estate investment and services and oil and gas producers sectors saw the biggest jump of Chinese investments with a C$1.4B and C$1.2B increase from 2015 to 2016. One of the highest valued transactions in 2016 was Anbang Insurance Group’s C$1.1B acquisition of four towers at Bentall Centre in downtown Vancouver.

How quickly Asia Pacific investments into Canada can recover will likely depend on when COVID-19 can be contained in both regions. However, Canadian policy makers have been quick to highlight why Canada is an ideal place for investment in the post-COVID world. Invest in Canada’s FDI Report 2019 emphasized that Canada brings four major advantages to foreign investors: ease of doing business, cost effectiveness, strong innovation and start-up programs, and preferential market access to more than 50 free trade partners.[96]

October 13th, 2020 marked the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Canada and China. Since 1970, the two countries have engaged in extensive trade and investment, and developed their cultural and personal ties through immigration and travel.

However, the celebration of the half-century of political, cultural, and economic exchange between Canada and China was marred by recent tensions between the two countries. The arrest of Meng Wanzhou, an executive of Huawei Technologies Co., in December 2018 has led to an increasingly strained political relationship. Two Canadian citizens, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, were arrested in China shortly after the executive’s detention.

Despite the political turmoil in the past few years, investment ties between Canada and China remain an important aspect of the bilateral relationship. Since 2003, China has become one of Canada’s top sources of FDI. Inward investment from China between 2003 and 2020 reached over C$90.8B, almost twice the C$45.7B of outward investment from Canada to China in the same period. Alberta has received the vast majority of the C$90.8B, with C$51.8B invested in the province between 2003 and 2020, largely due to oil and gas investments. However, in the past two time periods, 2015-2017 and 2018-2020, Chinese FDI in British Columbia has outpaced investment in Alberta. In 2015 to 2017, British Columbia saw C$4.3B in Chinese FDI compared to Alberta’s C$3.7B. From 2018 to 2020, the difference was even more pronounced, with British Columbia receiving C$9.9B compared to Alberta’s C$461M.

Where Chinese investments in Canada have been focusing on natural resources, Canadian investment in China has been largely concentrated in the real estate sector. The sector saw C$6B worth of investment between 2003 and 2020. The sectors that received the second and third most investment are the financial services and industrial transportation industries, with C$4.6B and C$4.5B invested respectively.

Interestingly, China’s alternative energy emerged as the top sector for Canadian investment from 2015 to 2017. This is primarily due to a transaction between Fulcrum Environmental Solutions Inc., a clean technology producer based in Edmonton, and DGF Shandong Industries Corporation, a China-based electrical company. Fulcrum agreed to deploy its technology to support DGF Shandong’s new thermal clean coal power plant for an investment of C$1.1B from DGF Shandong.

China will remain an economic power in the post-COVID world, and as conditions normalize in the next few years China’s economy will likely grow at unprecedented rates. China-Canada economic relations will continue to be important to both economies and the strong ties forged through investment will encourage the economic growth of each.

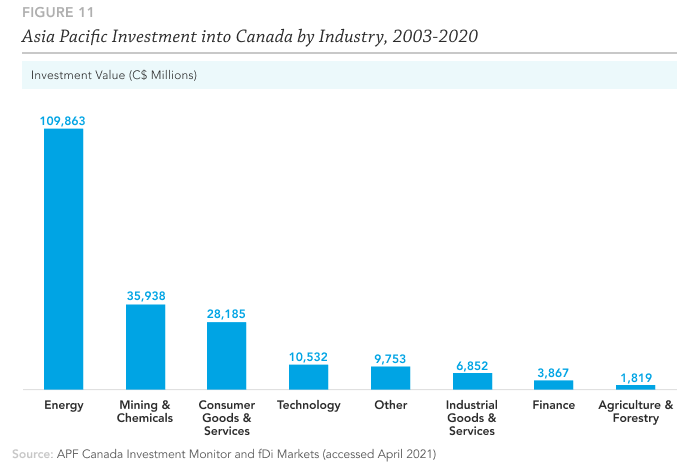

ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENTS IN CANADA’S SECTORS: NATURAL RESOURCES CONTINUE TO DOMINATE

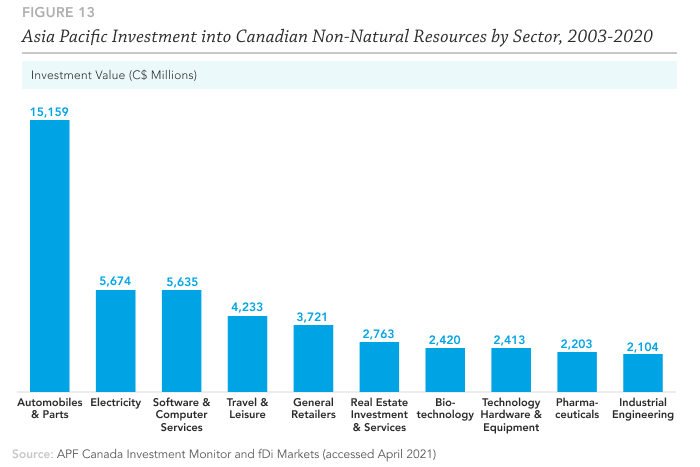

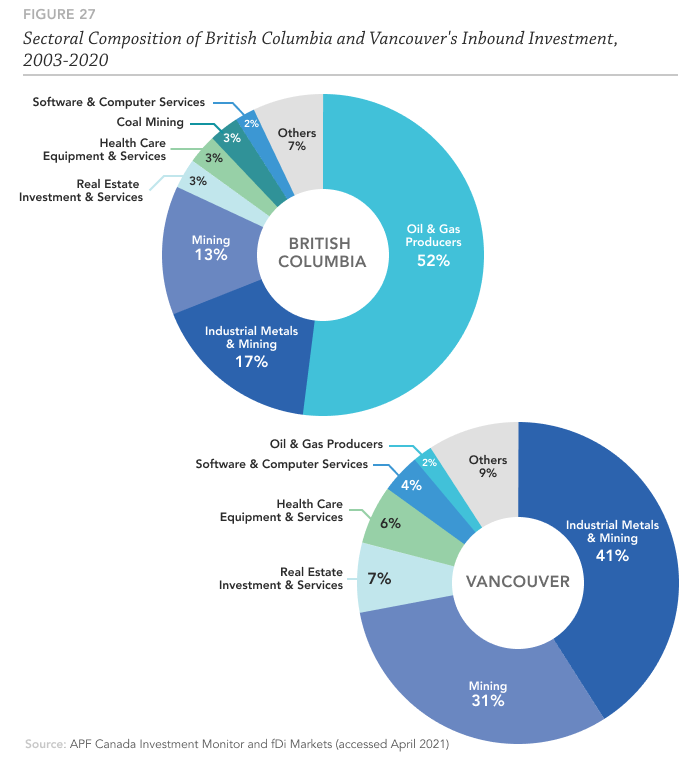

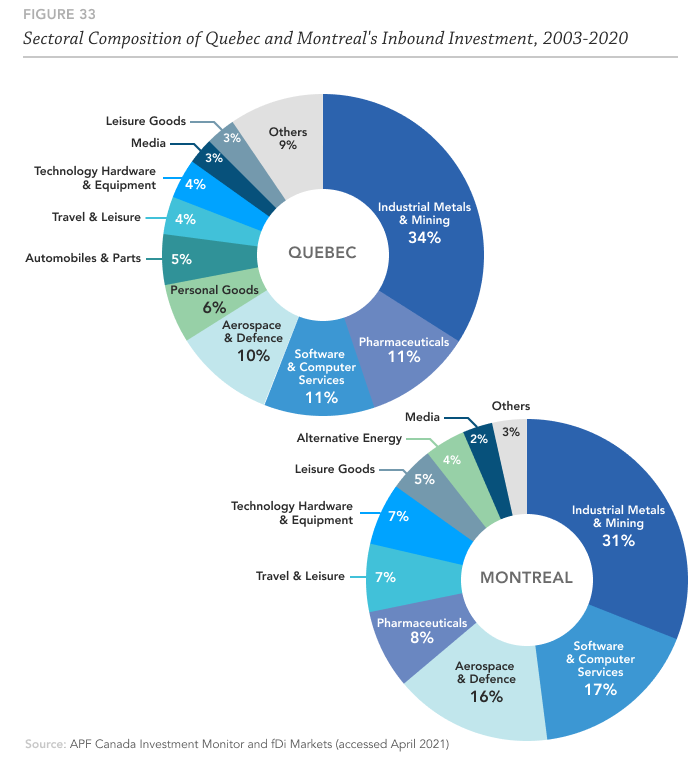

Inbound investments remain concentrated in Canada’s investment mainstay, natural resources. Since 2003, 71 per cent of investments from the Asia Pacific have been in natural resources, comprised of the energy, mining and chemicals, and agriculture and forestry industries. Among these industries, energy made up 52 per cent of total inbound investment, at C$109B, followed by the mining sector at 17 per cent, with C$35.9B, and agriculture at 0.8 per cent, with C$1.8B. However, consistent with declining investment trends worldwide due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the amount of investment flow in the natural resources sectors decreased considerably from C$6B in 2019 to C$1.2B in 2020.