Foreword

MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT & CEO, ASIA PACIFIC FOUNDATION OF CANADA

The increasing significance of the Asia Pacific as the driver of the new global economy underscores the need for Canada to strategically deepen and diversify its two-way investment links with this vital region.

Canada has been fortunate to have strong trade and investment partners in the United States and Europe, and those links will evolve but endure. But as Canada pivots to new Asian markets as part of its national trade diversification strategy, both policy-makers and the public have begun turning their attention to the foreign direct investment (FDI) flowing in and out of Canada. A number of questions permeate the discussion – and debate – around FDI: What amount of foreign investment comes into Canada, or flows into the Asia Pacific? Where does this investment come from, and where does it go?

This year, the Investment Monitor shifts its attention to Canadian and Asia Pacific FDI at the city level. New trends captured by the Investment Monitor show that Canadian cities are themselves hubs of activity and engagement, and are helping foster wider economic connectivity between Canada and Asia. It is our hope that this year’s report, by better aggregating and cataloguing investment trends at the city level, will fill the gap in the data that

is otherwise publicly available, and support business, government, and civil society as they navigate Canada’s necessary pivot to Asia.

On behalf of APF Canada, I would like to acknowledge the efforts of those involved in producing this report, especially our partner, The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary, and our sponsors – AdvantageBC, the Bank of Canada, Export Development Canada, the Government of British Columbia, and Invest in Canada. I would also like to extend my appreciation to our Advisory Council members – Sarah Albrecht, Eugene Beaulieu, Kursti Calder, Lori Rennison, Clark Roberts, Siobian Smith, and Stephen Tapp – for the valued feedback they have provided.

And finally, I would like to thank the members of our APF Canada research team who were responsible for writing and finalizing this report: Jeffrey Reeves, Vice-President, Research; Pauline Stern, Program Manager, Trade, Investment, and Innovation; Grace Jaramillo, Interim Program Manager, Trade, Investment, and Innovation; our Post-Graduate Research Scholars and Junior Research Scholars, Kai Valdez Bettcher, Mohit Verma, Nicole So, and Isaac Lo; and, APF Canada’s communications team for editing and designing the final publication, Michael Roberts, Communications Manager, and Sanya Arora, Graphic Designer.

Stewart Beck,

President and CEO, Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada

Executive Summary

The Asia Pacific is home to many of the world’s most dynamic and fastest-growing economies, and boasts unprecedented opportunities for foreign investment in a number of key markets – in terms of both opportunities for Canada to receive foreign investment and opportunities for Canadian investors to invest abroad. While there is anecdotal evidence to suggest that investors from Canada and the Asia Pacific are indeed crossing the Pacific, a lack of reliable public data makes it difficult to determine the volume, scale, or scope of the investments. To address this gap, the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) partnered with The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary. The APF Canada Investment Monitor aggregates raw data from APF Canada’s archive of investment deal announcements from 2003 to present (see methodology section for further details). Each year of the project corresponds with an annual theme; this year’s theme is two-way investment ties between cities.

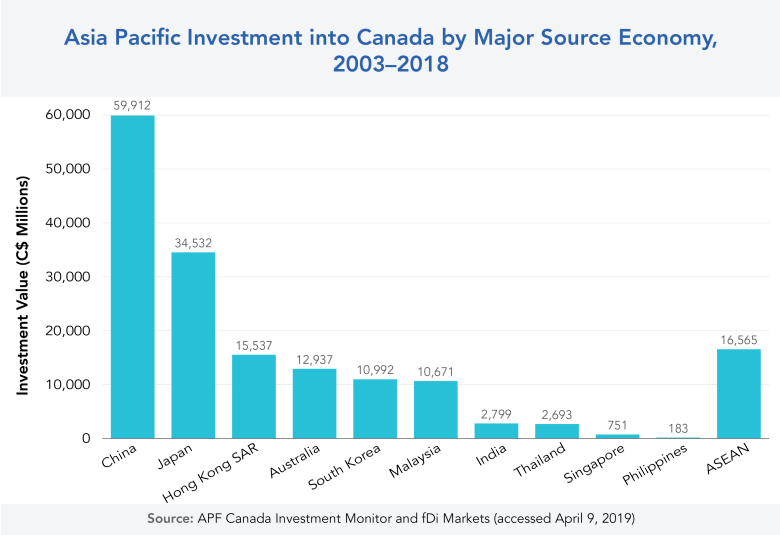

Data from the APF Canada Investment Monitor shows that Asia Pacific investment into Canada has grown in spurts from 2003 to 2018. The main sources of investment into Canada from the Asia Pacific are Mainland China, Japan, and Hong Kong, representing nearly 73 percent of the investment flows from the region to Canada. Canada’s natural resources industries, namely the energy industry and mining and chemicals industry, attracted the most investment. Even though the value was considerably larger for these two industries, the number of deals in other industries, such as consumer goods and services, technology, industrial goods and services, finance, and agriculture and forestry, accounted for nearly 69 percent of the total number of deals completed between 2003 and 2018.

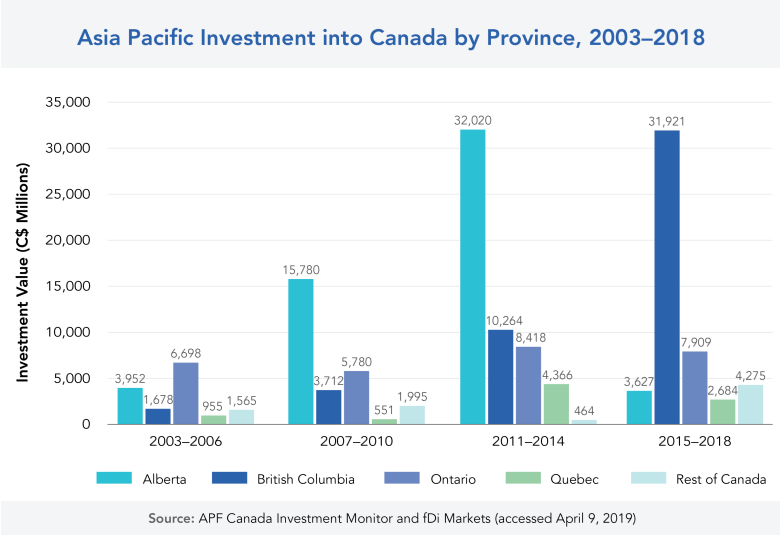

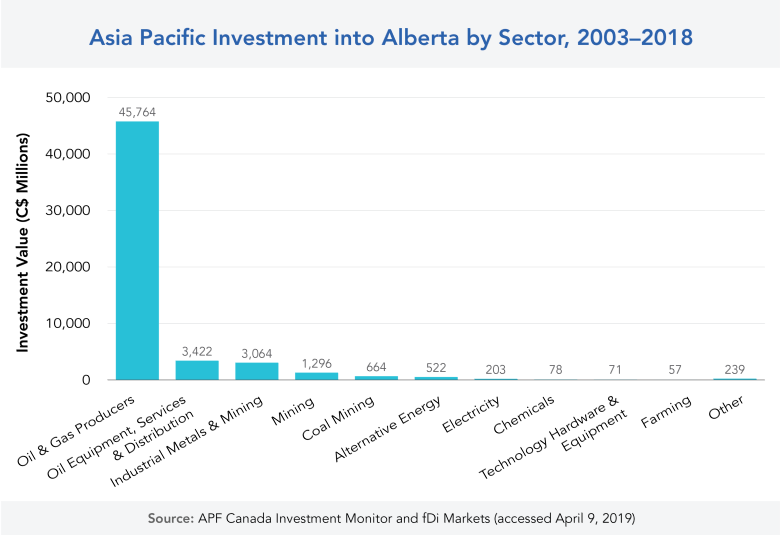

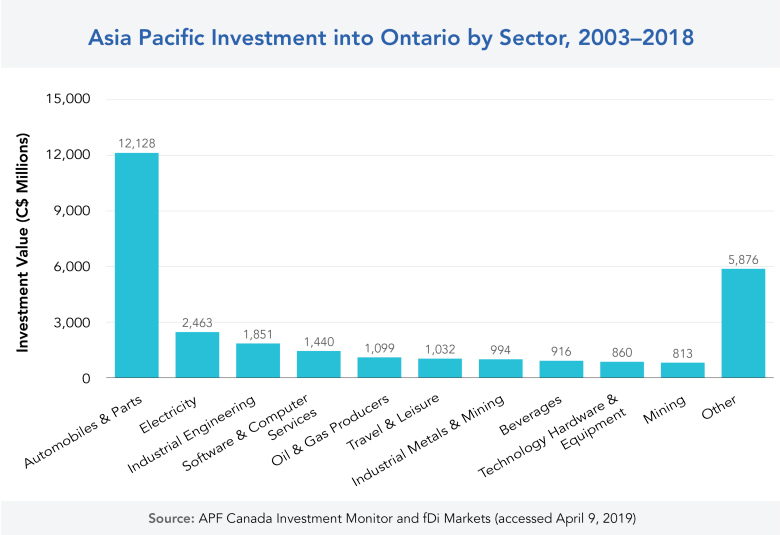

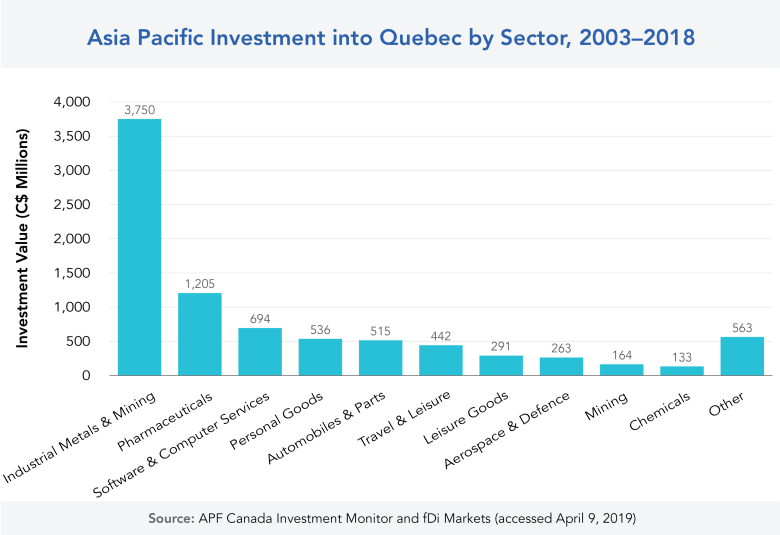

At the provincial level, Asia Pacific investment focused primarily on the four provinces with the largest economies over this period – Alberta, Ontario, BC, and Quebec. Each of these provinces attracted different types of investment. BC and Alberta attracted more energy-related investments; Ontario, automobiles and electricity; and Quebec, mining. Canada’s remaining provinces and territories have seen little investment, and that was primarily in oil and gas producers.

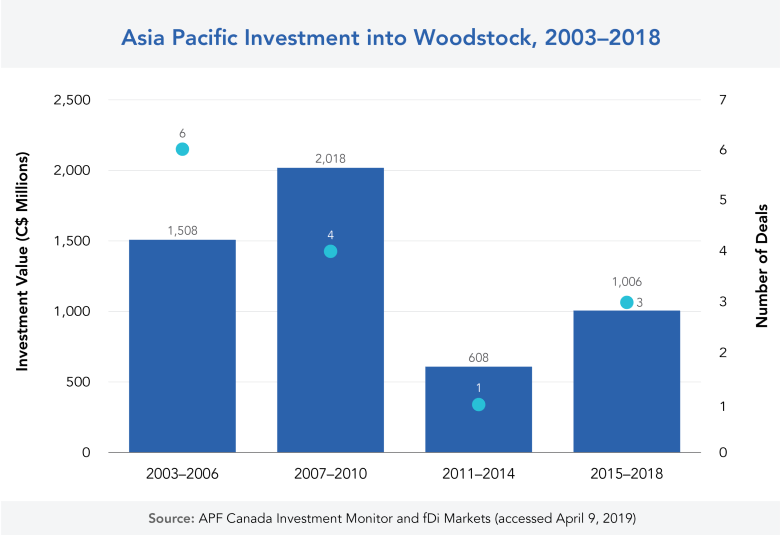

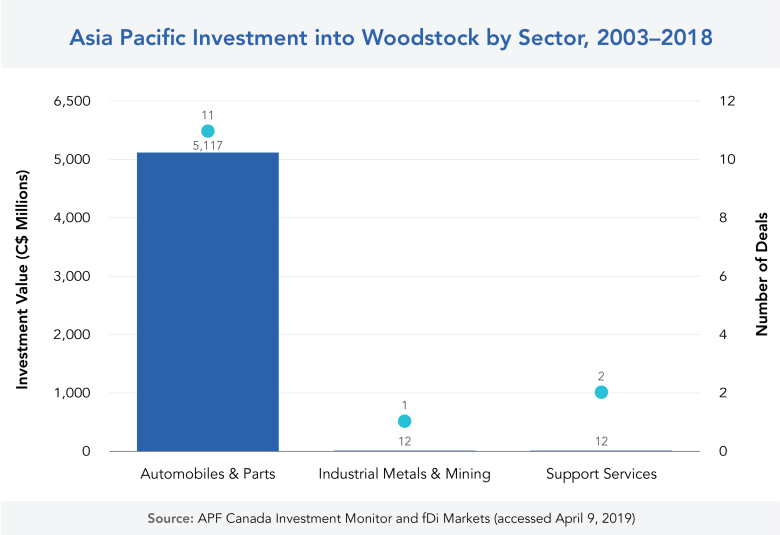

Overall, 165 cities and city-level regions in Canada have received investment from the Asia Pacific in the 2003 to 2018 period, each with a unique investment story captured by the APF Canada Investment Monitor. Surprisingly, the relative rankings of destinations show that many smaller Canadian communities punch above their weight when compared to much larger cities. Three cities – Calgary, Kitimat, and Vancouver – accounted for the majority of investment, mainly due to large investments in energy and mining. Vancouver, Toronto, and Calgary also brought in over 40 percent of the total number of deals over the period. Of the 15 largest destinations for Asia Pacific investment, eight are in the west (Alberta and BC), five in Ontario, with an additional one each in Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador. Many of the top destinations for investment in Alberta, BC, and Newfoundland and Labrador rank high due to a small number of large deals in oil and gas production, while repeated investments in the automotive industry led to several Ontario destinations also ranking high.

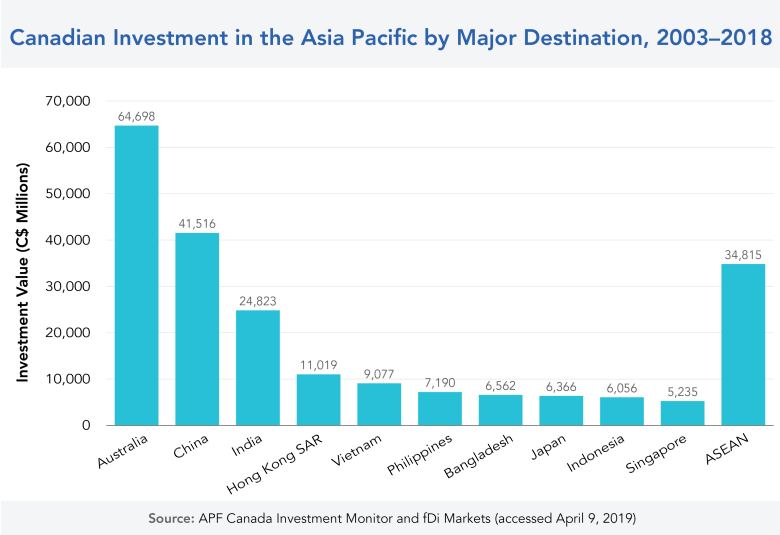

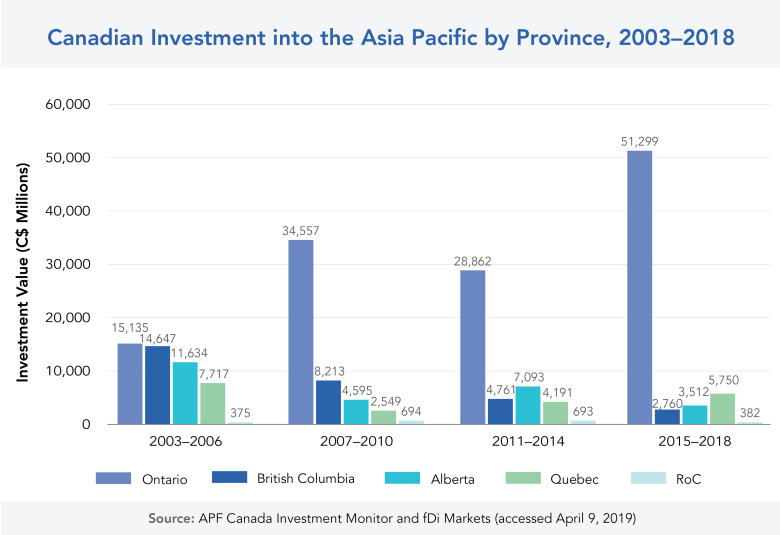

Canada’s investment into the Asia Pacific remained relatively flat into the middle of this decade, only to grow dramatically in the most recent years. The main destinations for Canada’s investment into the Asia Pacific are Australia, China, and India, representing nearly 63 percent of the investment flows from Canada to the Asia Pacific. The main industries that Canada invested in were the finance industry and the mining and chemicals industry. Even so, all other industries accounted for over 61 percent of the total number of deals completed from 2003 to 2018.

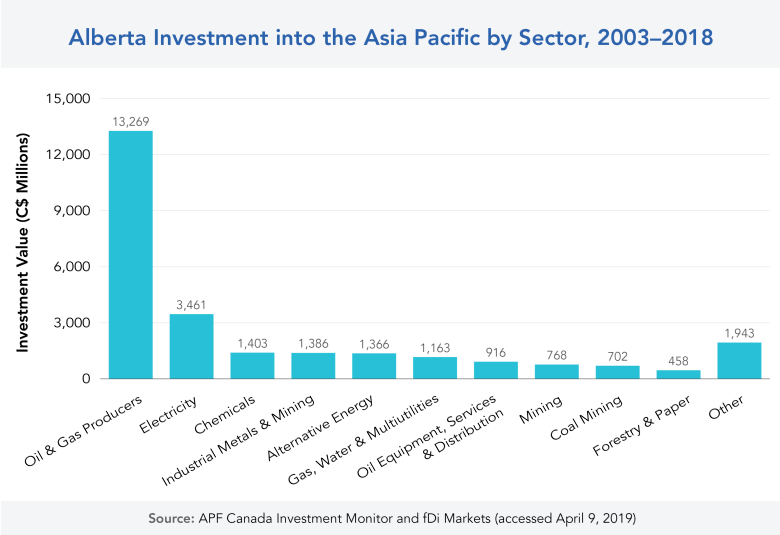

At the provincial level, investors from Ontario, BC, Alberta, and Quebec were the most active in Asia Pacific markets. Investors from Ontario focused their investment on financial and transport services, investors from BC and Quebec focused their investment on mining, and investors from Alberta focused their investment on energy. While investors from Canada’s other provinces and territories made noticeable investments in mining, these provinces drastically lagged behind the rest of the country in outward investment overall.

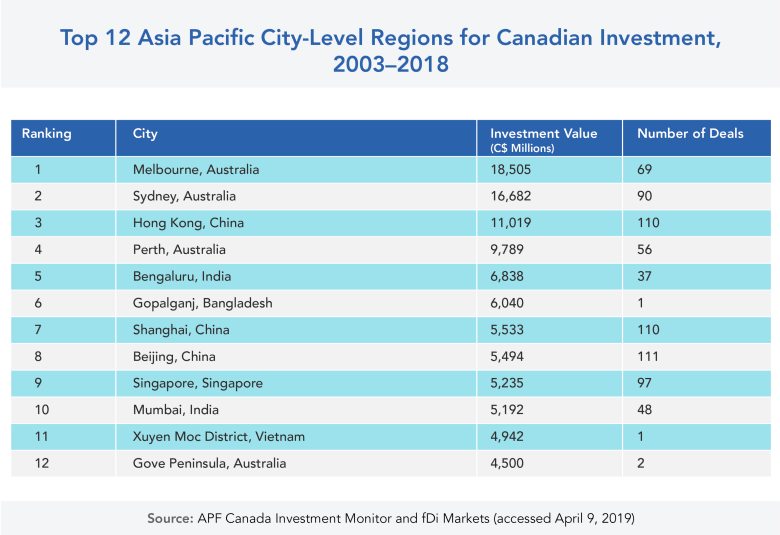

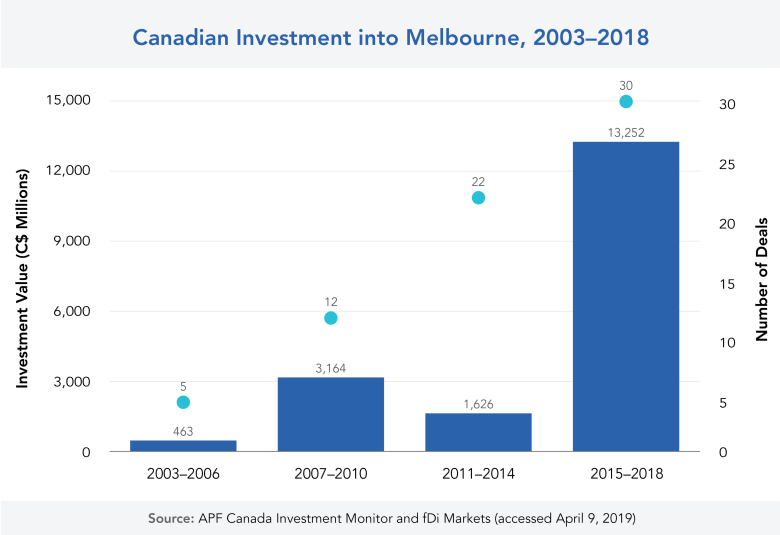

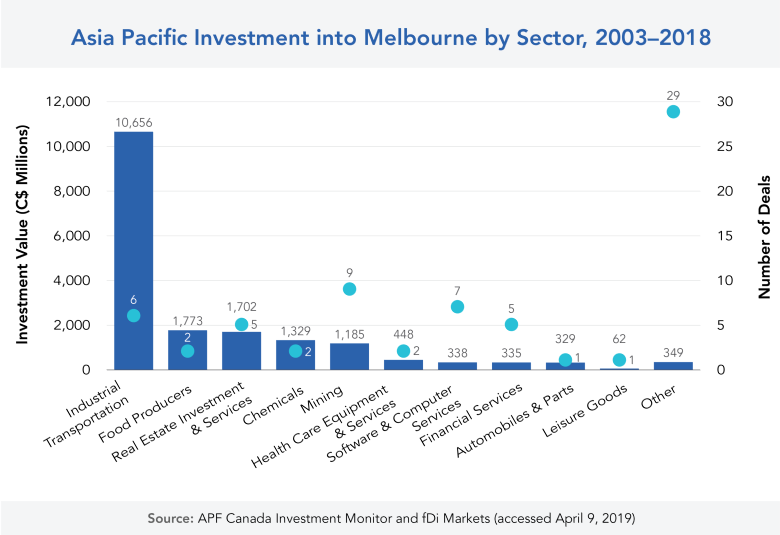

Canada’s investment footprint in the Asia Pacific is extensive, with 465 cities in the region receiving Canadian foreign direct investment over the last 16 years. Four cities – Melbourne, Sydney, Hong Kong, and Perth – received nearly 27 percent of Canada’s investment into the region, with a diverse basket of industries invested in between them. Additionally, Beijing, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Singapore, and Sydney received nearly 24 percent of the total number of deals from 2013 to 2018. Of the top 12 destinations for Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific, four are in Australia, three in China, three in South Asia, and two in Southeast Asia. In many cases, Canadian state-owned enterprises investing in real estate and transportation infrastructure have driven Canada’s largest investments in these cities. By looking down to the city level, the APF Canada Investment Monitor data also shows how some of the biggest destinations for Canadian investment are likely unfamiliar to many Canadians: names such as Gopalganj, Xuyên Môc District, and Gove Peninsula.

Although Canada’s investment relationship with the Asia Pacific has grown moderately over the past 16 years, the Asia Pacific remains far behind other sources of investment into Canada, and Canada represents only a small share of investment in the Asia Pacific. Canada needs to continue to leverage its strengths and build stronger ties with the region in the future in order to improve market access and position itself as an important investor in and investment recipient from the diverse economies that make up the Asia Pacific. APF Canada and The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary hope that the APF Canada Investment Monitor will shine a spotlight on Asia Pacific investment in Canada and encourage a greater understanding of how this investment contributes to Canada’s current and future economic prosperity.

Introduction

THE GROWING IMPORTANCE OF INVESTMENT TO AND FROM ASIA

The role of the Asia Pacific in the world has never been as big or as important in modern times as it is today. Continuous growth across the Asia Pacific has been met with significant flows to and from the region. Previously led by Japan, Australia, and South Korea, China is now the main economic driver of the region following record-breaking economic growth over the past 20 years. China’s rise in wealth has occurred alongside rapid economic shifts across Southeast Asia, as countries like Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia, once primarily recipients of foreign aid, begin to pique interest as investment destinations and participate in multilateral trade deals.

Observers forecast that the Asia Pacific will continue to cement its position as the centre of the global economy over the next 30 years. By 2030, the region is expected to encompass 65 percent of the world’s middle class[1], and by 2050, the region will contain four of the world’s 10 largest economies; according to PwC, China and India will both overtake the United States in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) at purchasing power parity.[2] Indonesia, currently ranking eight, is expected to become the fourth-largest economy by 2050 and will take Japan’s current spot, with Japan in turn expected to drop four spots and take Indonesia’s current spot at eight. Accordingly, the Asia Pacific is increasingly becoming a major source of investments for Canada. While investments from Japan and Australia are long established and at a sustained level, the majority of investments now originate from China from both private and state-owned enterprises.

At the same time, the foreign investment landscape that we have become accustomed to is changing. As a wave of nationalism sweeps through western democracies, sentiments toward foreign investment are changing, forcing foreign firms to reconsider their approach to foreign investments. A significant change within the past five years is the United States’ role as a “safe” destination for investments, as the current US administration has adopted an increasingly nationalistic approach to foreign investments. With all this combined, the Asia Pacific is becoming both an increasingly attractive destination for companies wanting to diversify away from traditional investment destinations such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe and an important source of investment capital for economies around the world.

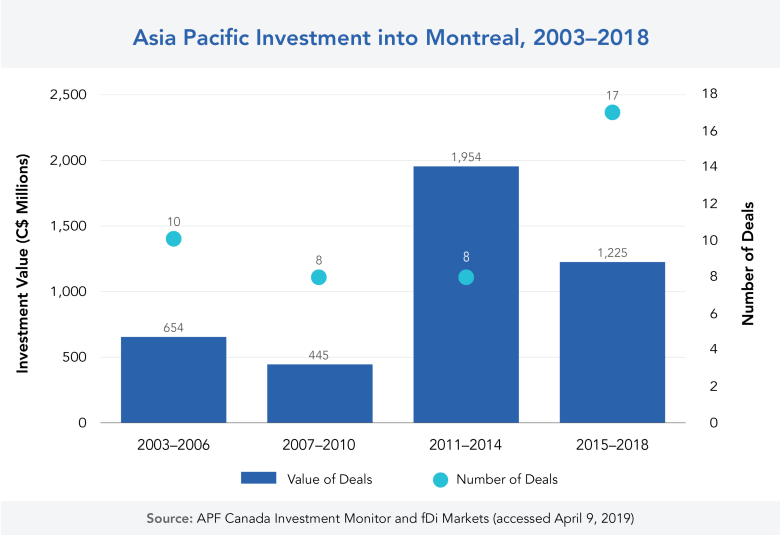

Cities are the epicentres of Asia Pacific investment activities in Canada. From 2003 to 2018, Asia Pacific investors channelled more than C$67B in Canada’s four most populous cities – Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, and Calgary. These investments fuel economic growth, induce technological “spillover,” increase productivity, and support job creation in the cities.[3]

HOW CANADA STACKS UP IN ITS INVESTMENT RELATIONSHIP WITH ASIA

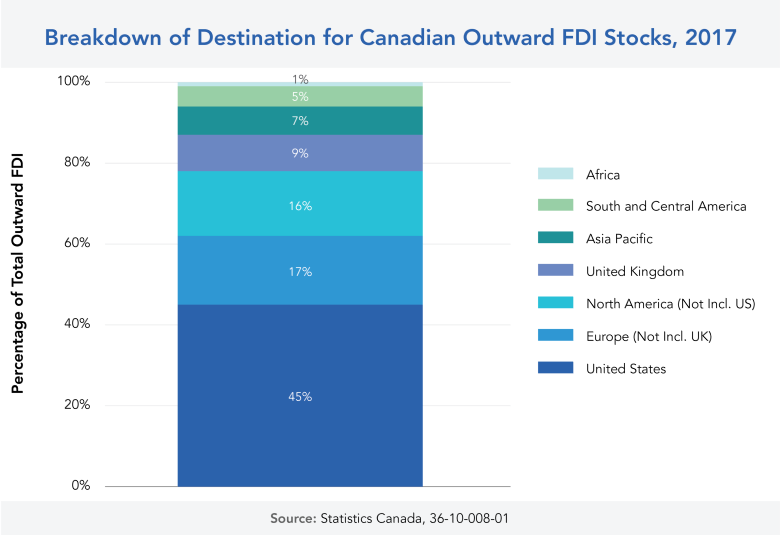

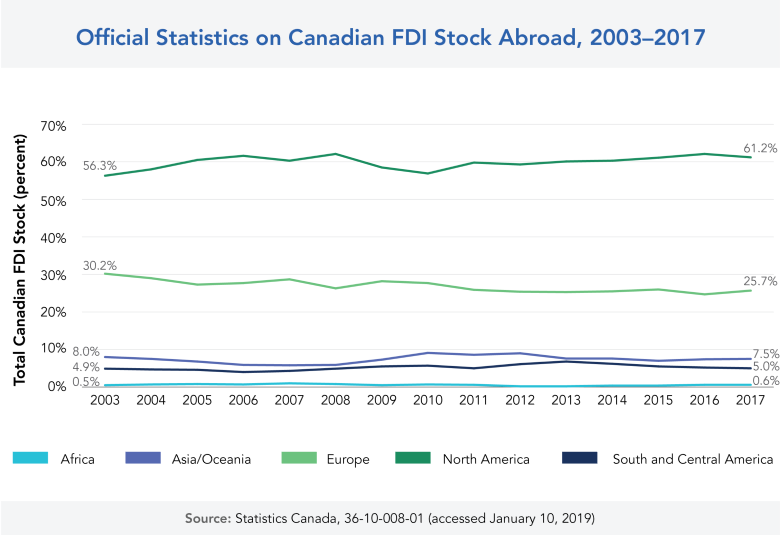

While Canada has enjoyed many aspects of its position next to the world’s largest

economy, the United States, this strategic positioning has come at the cost of investment

diversification. In terms of its investments abroad, Canada in 2017 sent 45 percent of its total

investments abroad to the United States and 24 percent to the European Union, the latter

of which included 9 percent of Canada’s total going to the United Kingdom. The Asia Pacific,

despite having a larger population and covering a larger geographical area than the European

Union, accounted for only 7 percent of Canadian investment abroad.[4]

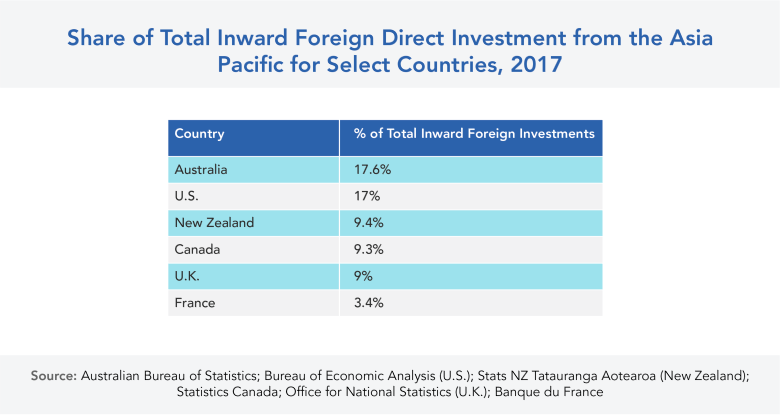

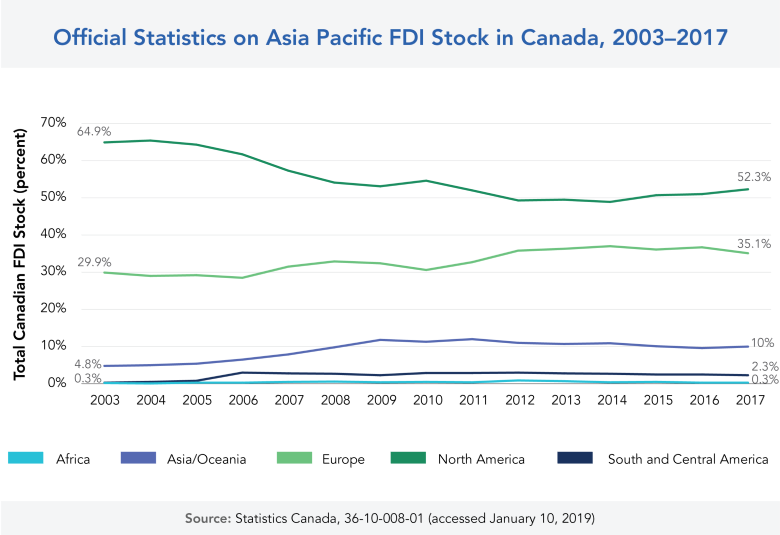

In 2017, investments from the Asia Pacific made up 9.3 percent of Canada’s total inward foreign direct investments (FDI). A similar level of inward foreign direct investment from the Asia Pacific was seen in New Zealand and the United Kingdom at 9.4 percent and 9 percent, respectively. This value was as low as 3.4 percent in France and as high as 17.6 percent in Australia. For comparison, investments from the Asia Pacific amounted to 17 percent of the United States’ total inward foreign direct investments in 2017; investments from Canada accounted for 11 percent of total foreign direct investments.

Even though investments from the Asia Pacific made up less than 10 percent of Canada’s total inward foreign direct investment, the amount Canada received was comparable to other developed countries of similar economic size. Likewise, the Asia Pacific region receives less in terms of investment amount from Canada than it does from the United Kingdom. In terms of furthering investment opportunities, Canadian businesses looking to invest abroad now have non-discriminatory access to key Asia Pacific economies such as Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and Vietnam through the implementation of the investment chapter of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). This is on top of Canada’s five foreign investment promotion and protection agreements (FIPA), also known as bilateral investment treaties (BITs), with Asia Pacific economies including China, Hong Kong, Mongolia, the Philippines, and Thailand. While Canada’s Asia Pacific network of free trade agreements (FTA) and BITs is especially strong when compared to the United States’ three BITs with Asia Pacific countries, it ranks far behind the United Kingdom, France, and Australia who have 16, 14, and 9 BITs with Asia Pacific economies, respectively.[5]

There are still plenty of opportunities for Canada to further investment opportunities with the Asia Pacific, and one possible avenue could be through expanding its current list of BITs. Canada currently does not have any agreements related to investments with Indonesia and is currently still in negotiations for a bilateral investment treaty with India. While an investment agreement does not guarantee greater investments between Canada and any partner economy, having an agreement in place can make regulations and treatment of investments in each party’s jurisdiction clearer for Canadian businesses.

WHAT OFFICIAL STATISTICS CANNOT TELL US

Despite the importance of FDI to the Canadian economy, little information is publicly available about foreign investment in Canada in terms of the number of deals, size of investment values, and distribution across regions and industries. While Statistics Canada, Canada’s national statistical agency, provides information on investment flows, it does not paint a complete picture of Canada’s foreign direct investment ties with the Asia Pacific.

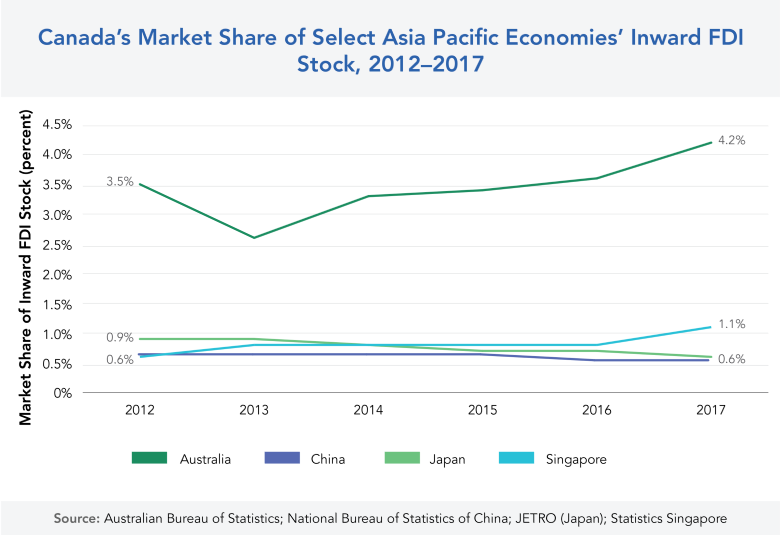

Official statistics across the region show that Canada is a small investor in the Asia Pacific. Data from the official statistics bureaus in China, Japan, and Singapore show that Canada’s market share of investment into Asia Pacific economies has been fluctuating between 0.5 percent to 1.1 percent for the past five years, while Canada’s market share in Australia’s inward FDI stock has steadily increased since 2013, but is still only just above 4 percent.

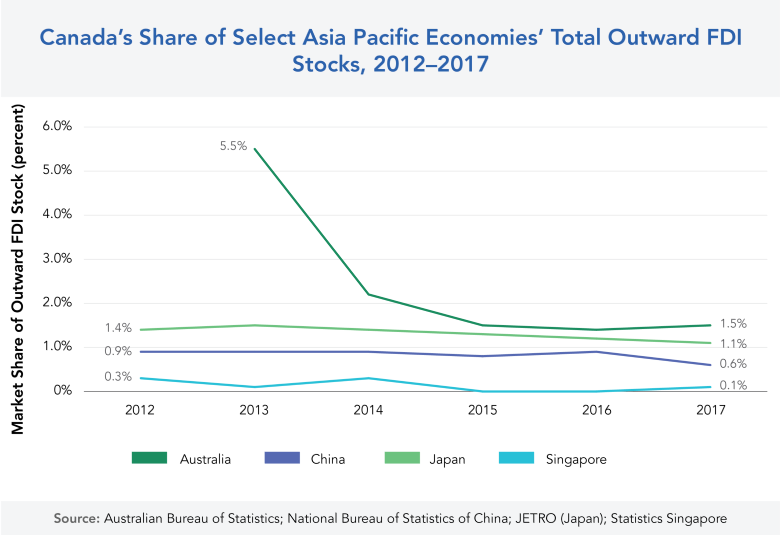

Likewise, when it comes to Asia Pacific investment into Canada, the region’s official statistics bureaus in China, Japan, and Singapore show that their investment into Canada has remained more or less consistently marginal, while the proportion of Australian outward FDI destined to Canada has decreased from 5.5 percent in 2013 to 1.5 percent in 2017.

Official statistics show investment stock at a national level and use a top-down approach based on the international standard balance of payment calculations, which official statistics bureaus generate from banking system reports and direct surveys. However, the broad-level public data from Statistics Canada is often unable to capture the ultimate sources and destinations of inbound and outbound investments, the subnational-level data (namely, investment ties at the provincial and city levels), and the industry breakdown of investment from each Asia Pacific economy.

The lack of publicly available data on the volume, scale, and scope of Asia Pacific investment in Canada has important effects on the public perception of investment relations between the two regions. For example, according to the 2016 National Opinion Poll conducted by the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada), Canadians estimated that FDI from China made up 25 percent of Canada’s total inward direct investment, while the actual figure at the time was closer to 3 percent. The polling further showed that this misperception of the size of Chinese investment in Canada is also tied to the negative opinion on foreign inbound investments, as Canadians who significantly overstated the value of Chinese investment in Canada were also more likely to say Canada has allowed “too much” investment into the country from China.

THE APF CANADA INVESTMENT MONITOR FILLS THE GAP

Given the limitations in the official statistics, the purpose of the Investment Monitor is to complement Statistic Canada’s investment data in order to provide a more comprehensive picture of the two-way investment relations between Canada and the Asia Pacific. APF Canada has partnered with The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary to develop its Investment Monitor and to track foreign direct investments at the establishment level. This has enabled the APF Canada Investment Monitor to add further detail beyond that available from official statistics and to unveil key trends in Canada’s investment ties with the Asia Pacific.

The inaugural Investment Monitor 2017 report looked at investment from the Asia Pacific in Canada, while the Investment Monitor 2018 report focused on Canadian outbound investment into the Asia Pacific. The reports depicted key trends on the sources of Canadian inbound and outbound investment from the national and provincial perspectives, as well as investment destinations in the Asia Pacific from the national perspective.

This year, the Investment Monitor 2019 annual report focuses on both inbound and outbound foreign direct investment between Canada and the Asia Pacific, while also highlighting key trends in the two-way investment ties at the national, provincial, and city level.

Cross-border investments can be separated into two major groups: 1) foreign portfolio investment (FPI) and 2) foreign direct investment (FDI).

1. FOREIGN PORTFOLIO INVESTMENT (FPI)

FPI is considered a temporary investment by a resident or enterprise of one economy into a financial asset of another economy. This investment involves a noncontrolling stake in an enterprise in the form of equity and/or debt securities as well as loans. For example, a resident of Australia buying a small share of stock on the TSX would be considered FPI.

2. FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT (FDI)

FDI is defined as a long-term or lasting-interest investment by a resident or enterprise of one economy into a tangible asset of another country. This type of investment is deemed “long term” or of “lasting interest” if it is either a greenfield investment or an acquisition of at least 10 percent of the equity or voting shares of an enterprise. This 10 percent threshold is considered a controlling interest in an enterprise and is what primarily distinguishes FDI from portfolio investment, since it usually coincides with a transfer of management, technology, and organizational skills along with capital. For example, a Japanese firm buying a 20 percent stake in a Canadian pulp mill would be considered FDI.

Source: APF Canada Investment Monitor

[1] Kharas. The Unprecedented Expansion of the Global Middle Class: An Update. Brookings Institute, February 2017. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/global_20170228_global-middle-class.pdf

[2] PwC. The World in 2050. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/world-2050/assets/pwc-the-world-in-2050-full-report-feb-2017.pdf

[3] Arcand. The role of Canada’s Major Cities in Attracting Foreign Direct Investment. Conference Board of Canada, May 2012. https://www.conferenceboard.ca/e-library/abstract.aspx?did=4817

[4] Statistics Canada. Table: 36-10-0008-01. 2018.

[5] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. International Investment Agreements. Investment Policy Hub.

The National Picture

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

- Today’s investment stories and landscape are very different from those of the post-global financial crisis (2007–2010, and even 2011–2014).

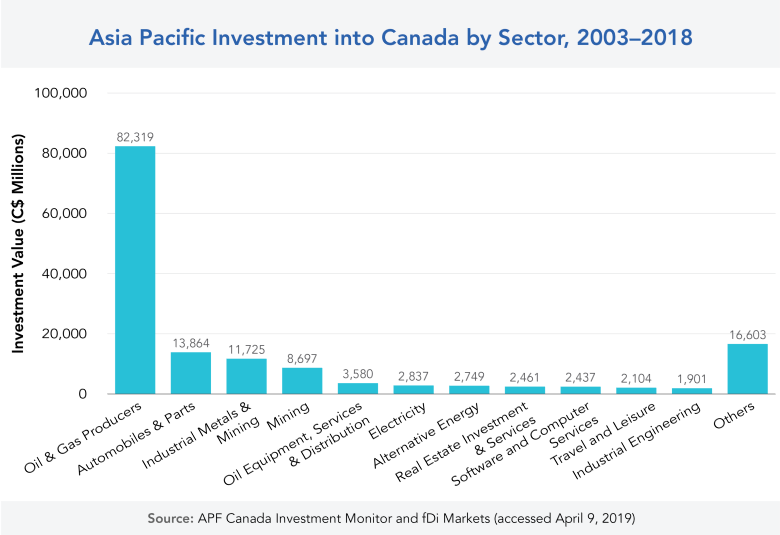

- The oil and gas, basic resources (mining), and automobile and parts sectors continued to dominate foreign direct investment into the Canadian economy, but there is also increased diversification into the real estate, financial services, and technology services sectors.

- China, Japan, Hong Kong, and Australia continued to be the key investors from the Asia Pacific into Canada.

- Canada is investing in Asia Pacific’s mining, industrial transportation, real estate investment and services, and electricity sectors, particularly in Australia and China.

NATIONAL DISCUSSION ON FLUCTUATION AND PARTNERS

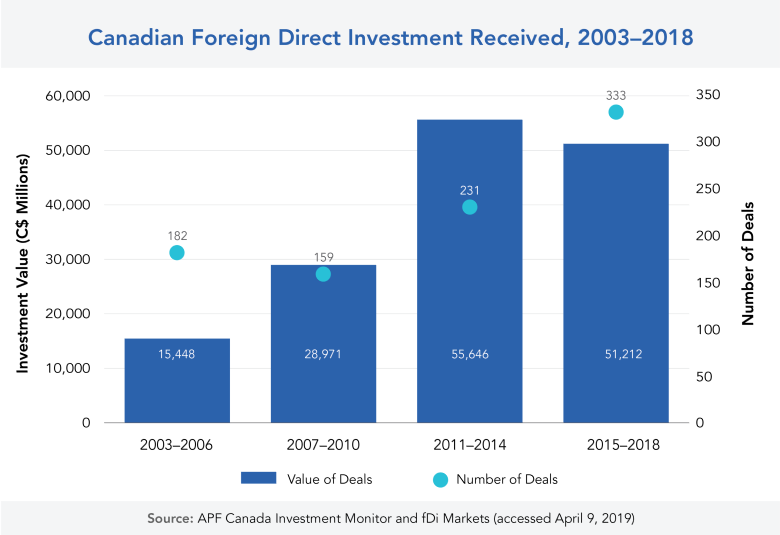

Over the past 16 years, investment from the Asia Pacific grew substantially in both volume and activity. For the period from 2003 to 2018, the APF Canada Investment Monitor captured C$151B in investments from the Asia Pacific into Canada through 905 deals from 14 Asia Pacific economies. Despite international economic tensions making significant global headlines in 2018, APF Canada Investment Monitor data shows that Asia Pacific investment in Canada has grown nine-fold over the past 16 years.

From 2015 to 2018, Canada continued to receive high foreign direct investment from the Asia Pacific, at C$51.2B over those four years, and additionally received the highest number of recorded deals (333 deals). The particularly high foreign investment dollar value stems in large part from a C$40B investment to build an export facility in Kitimat, BC. Of this deal’s dollar total, 60 percent (C$24B) was by Asia-based oil companies involved in LNG Canada – a joint venture between Shell, Petronas, PetroChina, Mitsubishi Corporation, and Korea Gas Corporation.

The trend of large investment deals from multinational corporations, particularly into Canada’s natural resources sectors, is consistent with the investment patterns from previous years and periods. For example, the exceptionally high foreign direct investment Canada received in the post-financial crisis period (from 2011 to 2014) was driven in large part by a few large multinational corporation deals, such as Mitsubishi Group’s C$3.2B investment in 2012, China National Offshore Oil Corporation’s C$16.7B investment in 2013, and Australia’s Woodside Energy’s C$2.2B investment in 2014. This resulted in large differences in year-to-year investment flows, and even across four-year periods. Despite the increased diversification into other sectors such as real estate, financial services, technology services, and pharmaceutical, oil and gas sectors continue to dominate Asia Pacific investment in Canada.

From within the Asia Pacific, China, Japan, and Hong Kong were the top investor source-economies from 2003 to 2018. From 2003 to 2018, China invested over C$59.9B in Canada, Japan invested C$34.5B, and Hong Kong invested C$15.5B. The scale of Chinese investment into Canada has been sporadic. China has invested significantly into Canada’s energy and mining industries since 2009 (currently valued at more than C$45B) and exhibited an extraordinary peak in the year 2013 at over C$17B. Although investments from Chinese firms continued to dominate the Canadian resources industries, investments in the past three years showed increased diversification into Canada’s real estate and health care sectors. Japan’s market share in the Canadian economy was consistently strong, particularly within Canada’s automotive sector. However, Japanese investment into Canada declined from 2003 to 2018. More recently, Japanese investment diversified into the retail sector, with players such as UNIQLO and Muji. Hong Kong had also been a significant investor into Canada’s energy sector. In the last three years, Hong Kong’s Husky Energy made significant investment (over C$4B) in Canada’s oil and gas sector in Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Southeast Asian nations such as Singapore and the Philippines invested more into the Canadian economy, but the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as an economic region still lagged behind the other Asia Pacific economies and captured only 5 percent of the inbound market share. ASEAN is one of the world’s fastest-growing economic regions and the Asia Development Bank has estimated its 2018 GDP growth rate at 5.1 percent, illustrating both a gap and an opportunity for Canada to strengthen its two-way investments with ASEAN and other emerging economies.

Although Canada expressed a growing interest in diversifying trade and investment opportunities beyond its traditional economic partners, Canada’s shift toward other markets over the past 10 years was modest. According to APF Canada’s 2018 National Opinion Poll, there is an inverse correlation between perceptions of a worsening Canada-US relationship and increased public support for further diversifying Canada’s economic engagement with the Asia Pacific – Canadians showed greater support for diversifying Canada’s economic engagement with the Asia Pacific. In the 2018 polling, 60 percent of Canadians agree that “the growing importance of China as an economic power is more of an opportunity than a threat,” whereas when the same question was asked in 2004, only 27 percent of Canadians agreed. As mentioned previously, Canada currently has only five FIPAs in force with the Asia Pacific economies: China, Hong Kong, Mongolia, the Philippines, and Thailand. Yet, key foreign direct investments from Asia Pacific economies in Canada were from China, Japan, Australia, and South Korea.

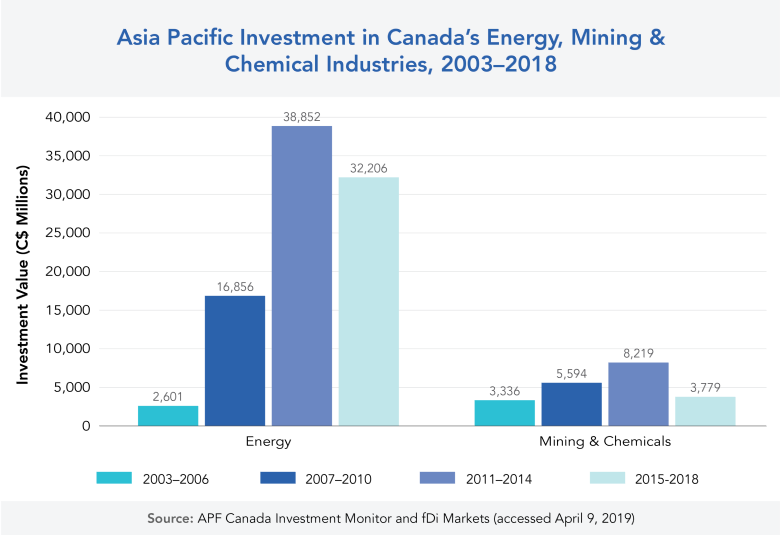

ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENTS IN CANADA'S SECTORS: NATURAL RESOURCES DOMINATE, DESPITE DECLINE

Asia Pacific investment dollar volumes continue to be deeply tied to Canada’s natural resource-based industries (energy, mining, and chemicals), which accounted for 74 percent (C$111B) of the total value of investment from 2003 to 2018. However, the energy and mining and chemical sectors experienced a significant drop in investment volumes and values in the last six years, since the purchase of Nexen by the China National Offshore Oil Corporation in 2013. The last six years’ decline in investment occurred in a context of declining commodity prices and a lack of large-scale investments matching the Nexen deal.

The trend of large investments from multinational corporations was seen in the automobile and parts, foods and beverages, real estate, and software and computer sectors as well. Notable examples included Japan’s Toyota Group’s C$708M expansion in Woodstock, Ontario, in 2018; Japan’s Sapporo Holding’s C$400M acquisition of Sleeman Breweries in 2006; China’s Greenland Group’s C$400M residential development project in Toronto; and India’s Tata Group’s C$292M acquisition of Teleglobe International Holdings in Montreal.

Within Canada’s natural resources industries, there was very low investment from the Asia Pacific in agriculture and forestry. India-based Aditya Birla Group’s purchase of the assets of Terrace Bay Pulp Mill in Ontario for C$279M in 2012 was the largest deal in the agriculture and forestry industry. There were no investments in agriculture and forestry between 2016 and 2018.

Although Canada’s natural resources industries were the significant driver of investments from the Asia Pacific, investments in consumer goods and services, industrial goods and services, and the finance and technology industries are growing. Specifically, there was high investment activity from the Asia Pacific in Canada’s automobile and parts sector (C$13.3B), real estate investment and services sector (C$2.5B), and the software and computer services sector (C$2.4B). Japanese automotive giants Honda, Toyota, and Nissan, as well as Hyundai, the Korean automaker, were heavy investors in Canada’s automotive industry for automobiles and parts.

The real estate investment and services sector and the software and computer services sector showed the greatest growth in the last four years. China and Hong Kong were strong investors in Canada’s real estate investment and services sector in BC and Ontario. For example, Canada’s Intergulf Development Group and China’s Modern Green Development Corporation have partnered to develop the Oakridge Transit Centre for TransLink Canada for C$450M. For the software and computer services sector, Canada saw the highest investment dollars from the Asia Pacific, valued at C$449M. In addition to giants such as South Korea’s Samsung Group and LG Corporation, Japan’s Fujitsu, and India’s Mahindra Group, China’s Alibaba and Beijing Xiaoju Technology Co. invested in Canada’s technology sector. In 2018, China-based Didi Chuxing, a transportation network company operating under Beijing Xiaoju Technology, invested C$119M to build a research facility for artificial intelligence and intelligent driving in Toronto.

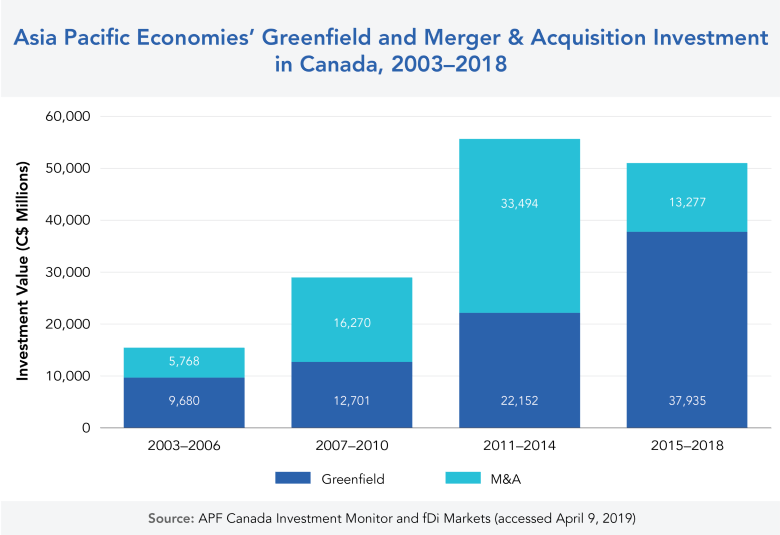

METHOD OF ENTRY: GREENFIELD DOMINANT, BUT GROWTH IN M&A

Greenfield remained the preferred investment method from Asia Pacific-based companies, but increasingly, investors are shifting their mode of entry from greenfield to mergers and acquisitions (M&A). From 2003 to 2018, there were 581 greenfield investment deals and 324 M&A deals. Although there were more greenfield investment deals, M&A investment was growing rapidly. For example, comparing the period from 2015 to 2018 with its previous period (2011 to 2014), the number of greenfield investments only grew by 26 percent, whereas the number of M&A deals increased by 77 percent. In 2017, there were more M&A deals made than greenfield deals, which had only ever occurred in 2009 and 2013.

From 2003 to 2018, the Asia Pacific economies invested a total of C$82.4B in greenfield investment and C$68.8B in M&A investment. Japan, China, and Malaysia were the largest players for greenfield investments. About 36 percent of greenfield investments were from Japan (valued at C$30B), followed by China at 24 percent (C$20B) and Malaysia at 12 percent (C$10B). For M&A investments, the top players were China, Hong Kong, and Japan. China accounted for 58 percent of all M&A investments (C$40B), followed by Hong Kong at 12 percent (C$8B) and Japan at 7 percent (C$5B). In terms of the number of deals, the top economies investing into Canada through greenfield investments are Japan (207 deals), China (142 deals), and Australia (68 deals). The top economies for M&A investments into Canadian markets are China (102 deals), Japan (53 deals), and Australia (53 deals).

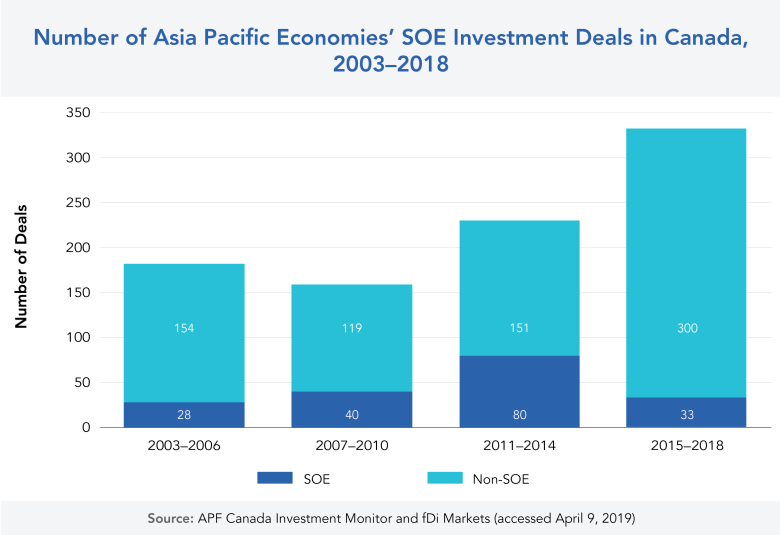

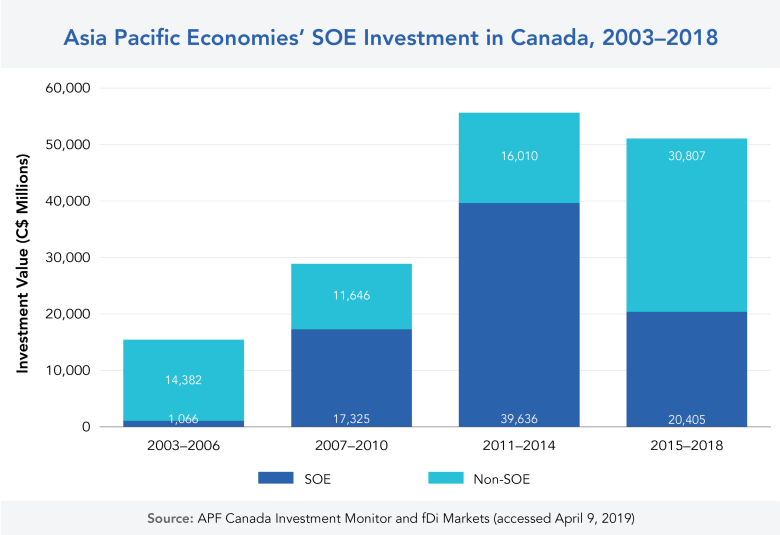

STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES IN CANADA: DESPITE THE PUBLIC ATTENTION, A DECLINING FACTOR

In the past five years, there has been a significant decline in investment from Asia Pacific-based foreign state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Although the C$16.7B acquisition of Nexen by Chinese SOE China National Offshore Oil Corporation made headlines in 2013, SOE investment from the Asia Pacific has fallen since that year. In the period from 2011 to 2014, there were 80 Asian SOE investment deals made in Canada with a collective value of C$39.6B. In contrast, only 33 deals were made from 2015 to 2018, valued at C$20.4B.

National polling showed Canadians were nervous about foreign investment from SOEs in Asia. In APF Canada’s 2016 National Opinion Poll, survey results showed there was never a majority in favour of SOE investment from any Asia Pacific economies. For example, 84 percent favour a private investment from Australia, while only 44 percent favour a state-owned investment. For China, a majority (51 percent) favour a private investment, while only 11 percent favour a state-owned investment. While Canadians were relatively positive on private investment from Asia, polling found that they were more cautious toward investment from SOEs.

Despite the public sentiment toward foreign SOEs, SOE investment accounted for half of the investment from the Asia Pacific and was valued at C$78.4B. Non-SOE investment from 2003 to 2018 was valued at C$72.8B. According to the Investment Monitor data, about 97 percent of SOE investment was in the natural resources industry, with Alberta’s energy sector exhibiting the highest investment in values and activities. Canada’s energy industry brought in C$63.7B of investment from Asia Pacific SOEs (accounting for 81 percent of the SOE investment from the Asia Pacific to Canada), while the mining and chemical sector brought C$12.2B of investment (accounting for 16 percent of the SOE investment from the Asia Pacific to Canada).

The SOE investment in Canada was largely driven by the Chinese, Malaysian, and South Korean economies, respectively. Canada saw C$47.5B of investment (61 percent of all SOE investment) from China, followed by C$12.8B (16 percent) from Malaysia, and C$5.8B (7 percent) from South Korea. In contrast, for non-SOE investments, the major Asia Pacific economies were Japan, China, and Australia, with cumulative investment values at C$31.4B (43 percent), C$12.4B (17 percent), and C$11.0B (15 percent), respectively, from 2003 to 2018.

On July 20, 2017, Shenzhen-based Hytera Communications Co. completed the purchase of Vancouver-based Norsat International Inc. for C$85.2M. What seemed like an ordinary deal on the surface ended up being the centre of a media storm fuelled by comments made by US security officials regarding the deal. With respect to sovereignty related to business deals done within one’s own borders, the comments coming from the United States regarding Canada’s apparent “jeopardizing [of] its own security interests to gain favour with China” appeared to violate Canada’s freedom to pursue its own economic agenda. However, it seems investment deals coming out of China into Canada and North America in general are being increasingly politicized and scrutinized for concerns regarding potential national security threats, especially for deals involving SOEs or those with strong ties to the Chinese government.

This was the case for Hytera’s acquisition of Norsat, with concerns that client information from Norsat’s previous dealings with the US and Taiwanese militaries could be compromised following the acquisition. Anbang Insurance Group Co. Ltd.’s purchase of Retirement Concepts, the owner of several long-term care facilities in BC, was also scrutinized by security pundits after Anbang faced issues in the United States when regulators attempted to trace the ownership and leadership structure within Anbang. The Anbang deal was automatically reviewed by the Investments Canada Act due to the size of the deal. Reports following the decision, however, highlighted that the Anbang acquisition passed the national security review part of the overarching review.

A proposed acquisition of Calgary-based Aecon Group Inc. by China Communications Construction Co., a Chinese SOE, in October 2017 was also scrutinized by security analysts and government officials in both the United States and Canada. The deal was eventually blocked seven months later by the Canadian government following a full national security review. Had the deal gone ahead, Aecon would have been barred from bidding on the construction contract for the Gordie Howe International Bridge connecting Windsor, Ontario, to Detroit, Michigan, a key trading point between the United States and Canada and a project Aecon was actively pursuing. Aecon eventually signed on to the bridge contract, after the deal with China Communications Construction Co. was blocked.

Questions now arise about Canada’s ability to continue promoting itself as a friendly destination for Chinese FDI, a major initiative set forth by the current federal Liberal government and several of Canada’s provinces. Rising national security concerns expressed by four of the Five Eyes intelligence sharing coalition (Canada being the remaining fifth) in regard to Chinese FDI puts pressure on Canada to follow suit. On the flipside, however, the Chinese government has expressed displeasure at having deals originating from its country being reviewed, and officials have gone as far as calling for retaliatory measures in response to blocking Chinese FDI. Now with ever-rising security concerns in western economies, the Canadian government must choose whether it should have a firmer stance on FDI flows from SOEs or let the market take its course.

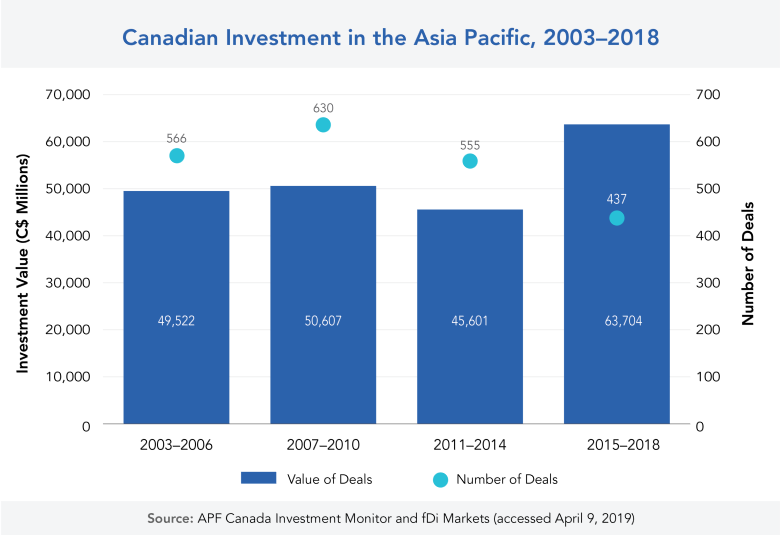

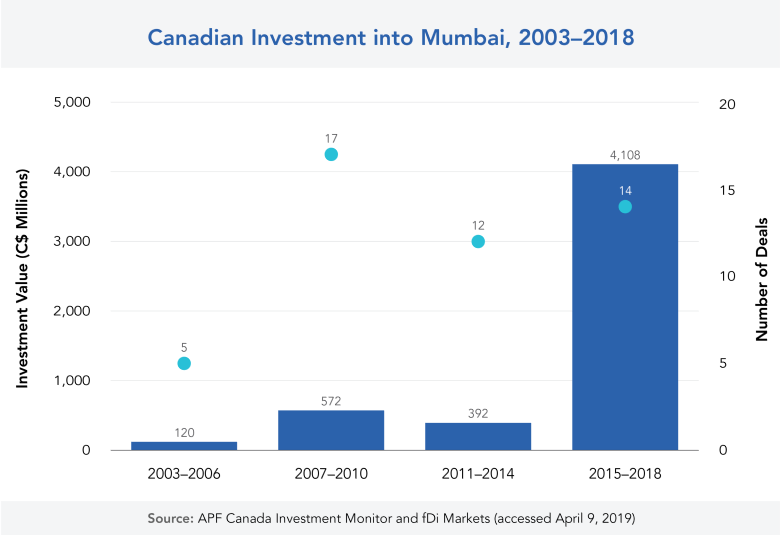

CANADIAN INVESTMENT IN THE ASIA PACIFIC: FEWER DEALS, BUT MORE DOLLARS

In the past three years, there was a decrease in the number of Canadian investment deals in the Asia Pacific. However, Canadian businesses are investing more dollars. Although the number of deals made between 2015 and 2018 dropped by 21 percent, from 555 deals to 437 deals, compared to its preceding period (2011 to 2014), the value of Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific had increased by 40 percent, from C$46B to C$64B.

In terms of investment values, Canadian companies have been investing in the natural resources-based industries in the Asia Pacific economies. The top sector for investment was mining. This sector consists of general mining, gold mining, mining for platinum and precious metals, and mining for diamonds and gemstones. From 2003 to 2018, the mining sector accounted for 10 percent (C$22B) of all investments. The top countries that Canada’s mining sector invested in were Australia, the Philippines, and Indonesia, for the highest dollars of investment, and China, Australia, and Mongolia for the highest number of investment deals. Canada invested more than C$8B in Australia’s mining sector, over C$4B in the Philippines’ mining sector, and over C$2B in China’s mining sector. To date, Canada has 149 deals in the mining sector with China, 127 deals with Australia, and 49 with Mongolia.

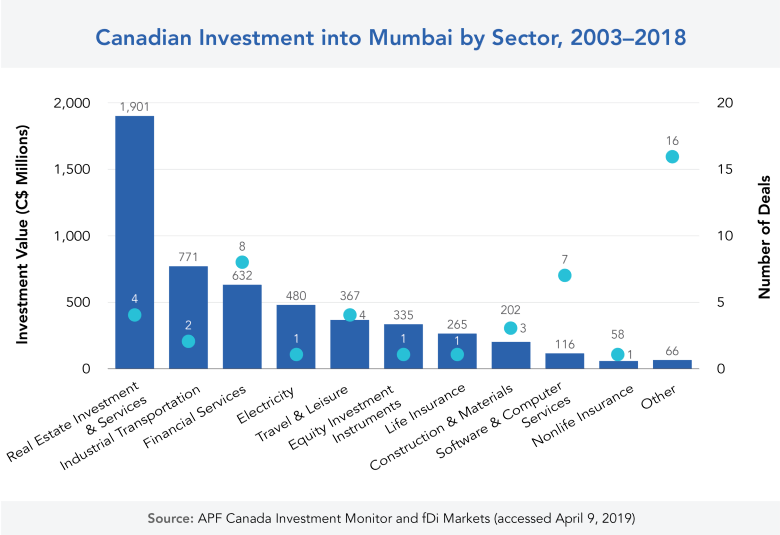

Outside the natural resources industries, Asia’s industrial transportation sector and its real estate investment and services sector saw increased investment from Canadian businesses in the last four years. Within the industrial transportation sector, Canada invested over C$20B, particularly in the Australian and Chinese economies. Australia saw the most dollars (C$11.8B) invested by Canadian companies such as Toronto-based Brookfield Asset Management Incorporated, while China had the highest number of deals (26 deals) and was the second highest (C$4B) in terms of dollars invested in the sector. Canada also invested over C$19B in the Asia Pacific’s real estate investment and services sector, with Australia, China, and India as the leading destination economies. The year 2018 saw the greatest investment from Canada into the Asia Pacific’s real estate investment and services sector in both volume and activity, valued at C$5.9B over 14 deals. The growth was largely driven by Canadian state-owned enterprises’ outbound investments in Australia’s real estate sector, such as from the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) and the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System.

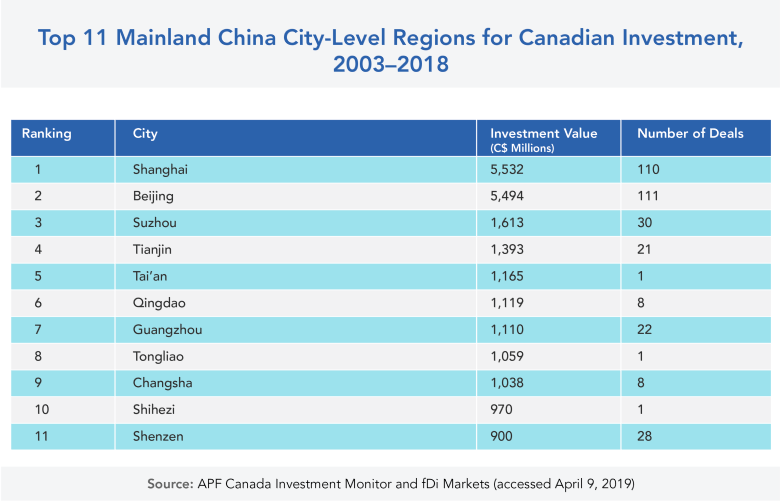

Overall, the top destinations for Canadian outbound investments remained Australia, China, India, and Hong Kong. The Investment Monitor data captured C$64.7B worth of Canadian investment into Australia, C$41.5B of investment into China, C$24.8B of investment into India, and C$11B of investment into Hong Kong. In 2018, Canada also saw its highest investment in terms of dollars to Australia’s economy at C$8.2B. The ASEAN nations accounted for 17 percent of Canada’s total outbound investment, valued at C$34.8B, with Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Singapore being the top ASEAN nations to see Canadian investment.

CANADA INVESTING IN A VARIETY OF SECTORS

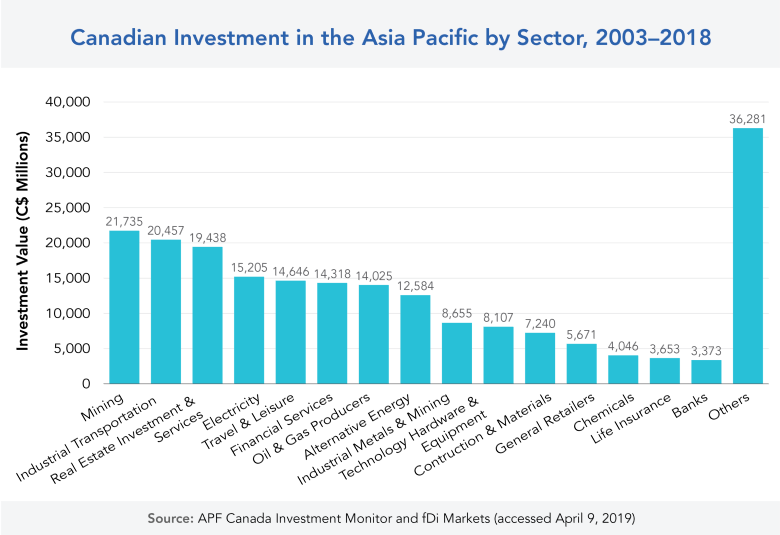

Between 2003 and 2018, the top sectors for Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific were mining, industrial transportation, and real estate investment and services. The mining sector (over C$21.7B) and the industrial transportation sector (over C$20.5B) each account for over 10 percent of the total outbound investment from Canada to the Asia Pacific, while the real estate investment and services sector (C$19B) accounts for 9 percent of Canadian outbound foreign direct investment.

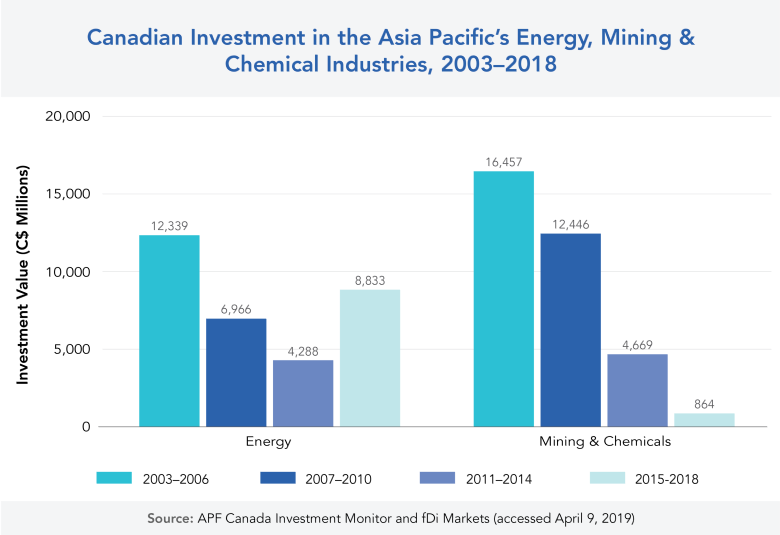

Although mining is the overall dominant sector for Canadian companies, Canada’s investment in the Asia Pacific’s mining and chemicals industry has dropped significantly in recent years. From 2015 to 2018, the mining and chemical industry was valued only at C$864M, an 81 percent drop compared to the previous period (2011 to 2014), which saw investments at C$4.7B, and a 62 percent drop from the 2003 to 2006 period, which had over C$12.4B in investments.

On the other hand, Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific’s energy sector was almost double in the period from 2015 to 2018 compared to the previous four-year period (2011 to 2014). In the last four years, Canadian companies invested over C$8.8B in Asia’s energy sector. Notably, in 2015, Toronto-based solar energy firm SkyPower Global made a C$6.5B investment in Bangladesh’s solar power sector.

Coal’s run as the go-to source for energy and heat is coming to an end for a large portion of the world. Many advanced economies at the national or state level in Europe and North America are abandoning coal in favour of cleaner and more renewable energy sources such as nuclear, solar, or wind. Asian countries are attempting to make a similar transition in the coming years as major cities like New Delhi, Beijing, and Seoul – to name a few – get choked by smog and fine dust particles resulting from activities related to coal use. Countries like India and China continue to use coal as it is relatively cheap compared to other sources, but government policies are starting to acknowledge the problem burning coal creates. In a speech at the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos in 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping recognized the negative effects of climate change and called for a domestic “green shift” toward the use of alternative energy.

Helping pioneer this transition of energy sources in Asia is Guelph, Ontario, based Canadian Solar Inc. After establishing itself through a contract with Volkswagen Group, Canadian Solar capitalized on the renewable energy wave of the mid-2000s as governments offered large incentives for renewable energy solutions, including solar panels and components. Since Canadian Solar’s inception in 2001, it is now one of the world’s largest producers of solar panels, earning well over C$3.3B in revenues in 2017. The company has a significant presence in the Asia Pacific region, with a manufacturing plant in Changshu, China, and numerous solar farm projects in Japan, China, and Southeast Asia. Recently, the company made a foray into new markets, and 2018 saw the company open its first plant in India in a project worth C$20M. In 2019, it will enter South Korea for the first time with a project worth C$82M to set up a solar photovoltaic project in Gangwon.

As more of Asia begins transitioning from coal to other forms of energy sources, Canadian Solar’s long-standing presence in the region, along with its track record of producing quality solar farms, shows that Canadian investments in the energy sector can go beyond oil and gas. Canadian Solar is also part of a larger wave of Canadian companies exporting alternative energy sources in Asia. Since 2007, Canadian companies have taken part in nearly 80 deals involving the production, installation, or implementation of renewable energy technology in Asian economies.

In non-resources-related industries, Canadian companies in the real estate investment sector exhibited strong growth in the period between 2014 and 2018. In that period, the CPPIB made heavy investment in the Asia Pacific’s real estate and financial sectors, valued at more than C$4B in total. The CPPIB also drove the growth in the industrial goods and services industry in 2018. That year, the CPPIB invested over C$1.8B into the Asia Pacific’s industrial transportation sector, and over C$1.7B into the construction and material sector.

The food producer sector in the consumer goods and services industry also saw major investments, particularly by Montreal-based Saputo Inc. In 2018, Saputo acquired Murray Goulburn in Australia for C$1.3B and became the first and largest foreign-owned company in the history of Australia’s dairy industry.

CANADIAN FIRMS STILL ENTERING WITH GREENFIELD DEALS

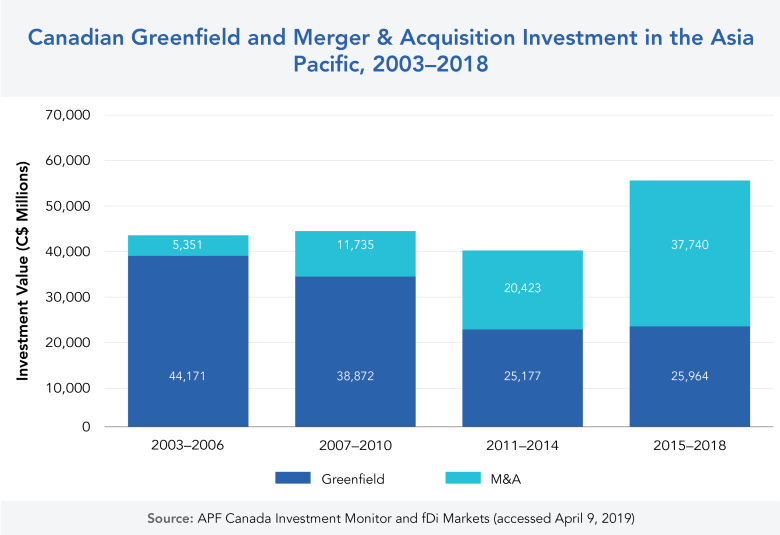

In terms of the type of investment in Asia Pacific economies, Canadian companies heavily favoured greenfield deals, although the investment amount in M&A deals has also increased since 2003. Overall, there were a total of 1,558 greenfield deals from 2003 to 2018, accounting for 71 percent of the investments and valued at C$134B, while the M&A deals accounted for 29 percent of the investments, at 630 deals and a value of C$75B.

However, although greenfield remained the preferred investment method into the Asia Pacific, the dollars of investment generated from M&A deals have increased since 2003 and surpassed the investment amounts from greenfield deals starting in 2016. During the period between 2003 and 2006, only 11 percent of investment came from mergers and acquisitions (C$5B), whereas between the period from 2015 to 2018, the investment dollars generated from M&A deals accounted for 59 percent of the total investment (valued at almost C$38B).

In terms of the number of deals, Chinese firms had the greatest number of greenfield investment deals and dollars invested from Canadian firms. There were 589 greenfield investments from Canada to China, which accounted for 25 percent of all greenfield investment. Following China, other leading Asia Pacific economies for greenfield investment from Canada were India (182 deals), Australia (173 deals), and Singapore (93 deals). For the value of greenfield investment from Canadian firms, China is the top destination economy valued at almost C$34B, followed by Australia at C$22B, India at C$17.6B, and Vietnam at C$9B.

For M&A deals, the top destinations are Australia and China. Australia accounted for over 34 percent of M&A deals, with 215 deals and over C$42B in investment, and China accounted for over 27 percent of M&A deals, with 167 deals and over C$7.9B in investment.

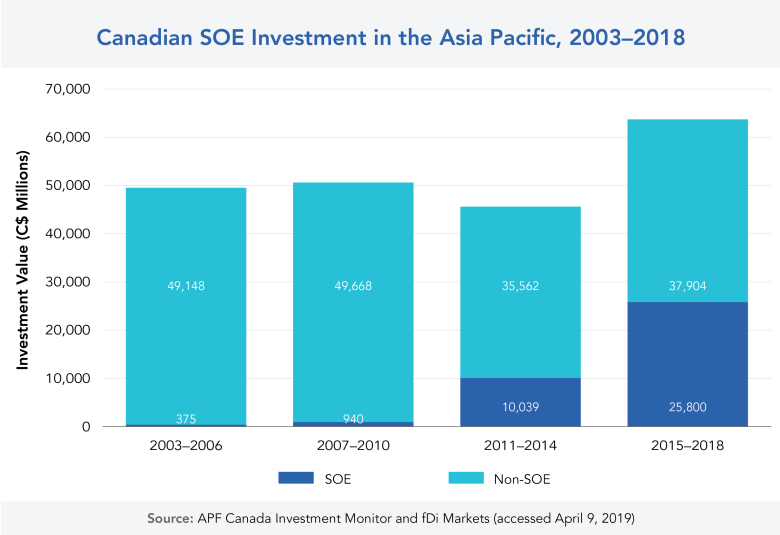

CANADA'S SOES NOW MAKE UP THE MAJORITY OF YEARLY FLOW

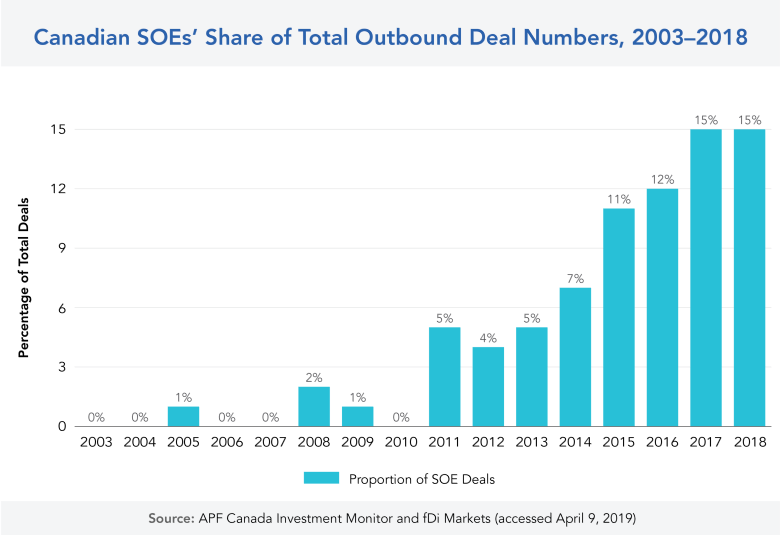

While lively discussion surrounds foreign state-owned investments into Canada, less attention is paid to the active and growing presence of Canada’s own state-owned investments across the Asia Pacific. Although making up just 0.2 percent of deals in the 2003 to 2006 period, with a total value of C$375M, Canadian SOEs have consistently increased their role as investors in terms of both share and absolute values, to the point where 15 percent of Canada’s deals in the region, valued at C$25.8B, were conducted by Canadian SOEs in the 2015 to 2018 period. Even more notably, the most recent two years are the first time a majority of Canadian investment originated from SOEs: 54 percent in 2017 and 61 percent in 2018.

Canada’s SOEs are making bigger deals on average than their private counterparts, too, and are increasing their number of deals. Thus, while only one outbound SOE deal occurred from 2003 to 2006 – a mere 0.2 percent of that period’s activity – the most recent 2015 to 2018 period saw 58 SOE deals – or 15 percent of activity. In 2015, SOEs made up more than 10 percent of deal activity for the first time, and increases in SOEs’ share of total activities have persisted to 2018 (15 percent).

In all, Canada’s SOEs have invested C$37.2B into the Asia Pacific, to non-SOEs’ C$175.4B. Of that C$37.2B, nearly half, or C$17.4B, has flowed from SOEs into just one economy: Australia. Flipping the script of Canadian worries over incoming SOE transactions, Canada’s SOEs have made significant deals in Australia’s real estate, transportation infrastructure, and financial services sectors.

The Provincial Picture

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

- BC and Alberta are investing less in the Asia Pacific relative to previous years.

- Investments flowing to Ontario are at their highest point; BC and Quebec are down, but above pre-recession levels.

- Alberta is still reeling following oil price shock, but slowly recovering.

- The big four provinces are seeing more diversified investments from Asia plus investments in their industry of strength.

- Investments into other provinces/territories are often characterized by a single or a few “whale” deals.

- The territories and the Prairies are playing to their strengths; Atlantic Canada is seeing more investments in support services.

CANADA'S BIGGEST PROVINCES CONTINUE TO LEAD INVESTMENTS, BUT SOME MORE THAN OTHERS

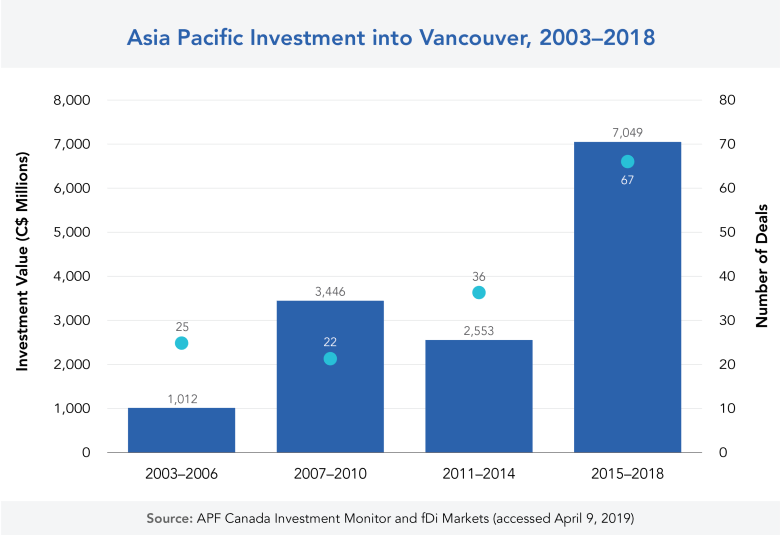

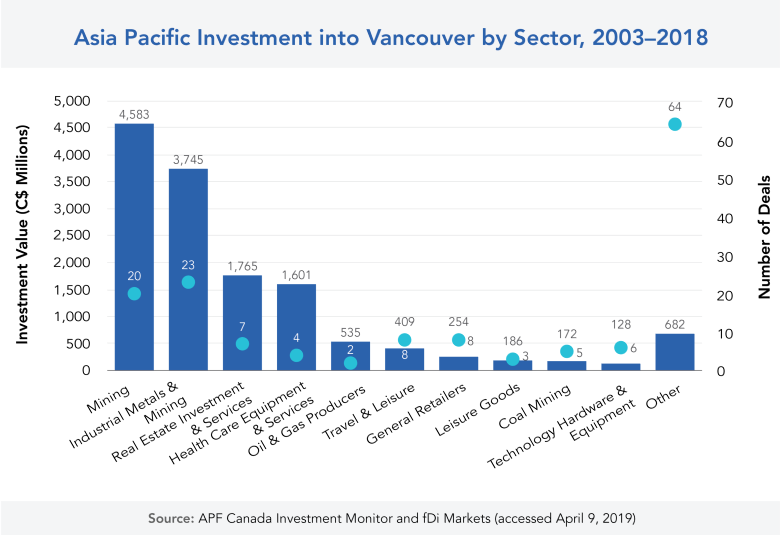

The flow of two-way international investment between Canada and the Asia Pacific continues to remain concentrated between Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, and BC, Canada’s largest provinces by GDP. As shown by APF Canada’s Investment Monitor, BC, Alberta, and the rest of Canada saw inward investments exceed outward investments following the recession, whereas the opposite was the case in Ontario and Quebec. Ontario was also the only province to have outward investment in excess of their pre-recession levels, while Quebecois investments in the Asia Pacific exceeded the investments the province received from the Asia Pacific in all years considered aside from the period between 2011 and 2014. All other provinces saw declines in their level of investment in the Asia Pacific. The other provinces fared a bit better in terms of receiving investments from the Asia Pacific, as only Alberta has seen fewer investments from the Asia Pacific since the Great Recession. BC was the standout here as the province has seen investments from the Asia Pacific grow nearly five-fold since the recession relative to pre-recession levels.

Inward investments into BC, Alberta, and Quebec from the Asia Pacific have primarily gone into the same sectors as did previous investments from the Asia Pacific. For BC and Alberta, these sectors include oil and gas. BC and Quebec also saw investments in their mining sectors, and Ontario saw sustained investments in its automobile and parts sector. At the same time, these provinces more recently saw investments shift away from their strengths and into more technology-focused sectors. In the past few years, Quebec has seen rapid development of its technology sector and has seen itself transform into a hub for artificial intelligence (AI) research and development. BC and Alberta have also seen increasing investments into

the alternative energy sector. Beyond the big four provinces, deals from the Asia Pacific have been sporadic, and often are characterized by “whale” deals – one or two major investment deals from a single firm that outweigh other investments into the province. Recent deals in the provinces outside the big four have been in business support-related sectors, such as industrial transportation and computer services.

A similar story is taking place for outward investments into the Asia Pacific from the provinces. BC, Alberta, and Quebec invested in the same sectors that the companies from the Asia Pacific invested into the provinces. There were, however, some increased investments into sectors that had previously received little focus. For example, BC companies have made investments in software and computer services, Quebecois and Albertan companies are making investments in the industrial transportation sectors, and some Quebecois and Ontarian companies made major deals in the food products and real estate services sectors, respectively. Looking at the rest of Canada, investment deals again have been sporadic and pale in comparison to the big four provinces, with investments from the territories virtually non-existent.

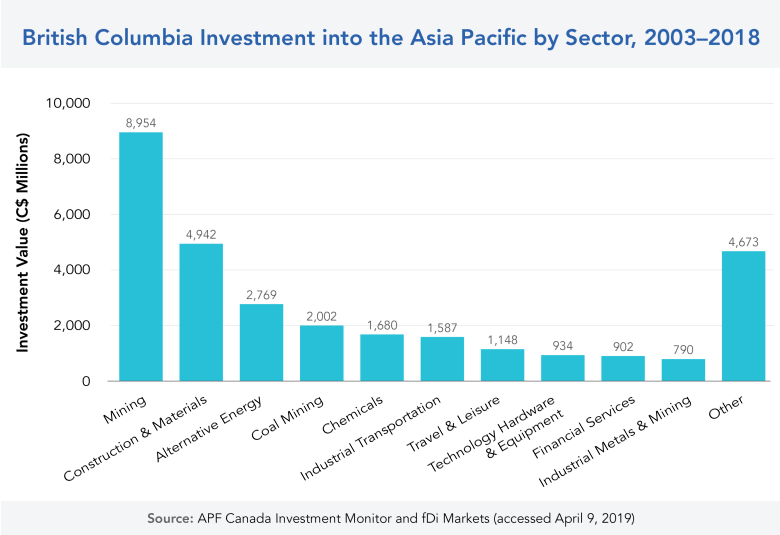

BRITISH COLUMBIA: CONTINUING AS A GATEWAY TO THE PACIFIC

BC is geographically adjacent to the Asia Pacific region and strategically positioned to be Canada’s pacific gateway to developing and leading two-way investment ties between Canada and Asia. In 2017, Asia accounted for more than 40 percent of the province’s merchandise exports and 45 percent of its merchandise imports.[6] Although BC has been the second-largest Canadian province investing in the Asia Pacific over the past 16 years, the value of its investments into the region has declined relative to the investments the province has received from the Asia Pacific over the same period. In the early 2000s, investment ties between BC and the Asia Pacific were mostly characterized by outward investment flows from BC to the Asia Pacific. However, later in the decade – as BC investments into the Asia Pacific declined – investments into BC from the Asia Pacific surged; the direction of investment flow between the two regions reversed.

Investments from the Asia Pacific into BC remain well-diversified relative to other provinces in Canada, with the oil and gas and mining sectors as the leading sectors from 2003 to 2018. These sectors combined account for over 76 percent of BC’s total inward investment for the last 16 years. In the last four years, investment interests from the Asia Pacific have grown in the province’s other sectors. For example, BC’s real estate investment and services saw over C$1.7B in investments between 2015 and 2018, compared to virtually no investments before 2015. As well, the province’s health care equipment and services sector saw C$1.5B in investments since 2015, compared to C$52M in investments between 2003 and 2006.

In 2018, the province saw a drastic investment uptake from the Asia Pacific in its oil and gas producer sector. This rise in investment was driven by a C$40B liquified natural gas (LNG) project in which a number of Asia Pacific investors acquired a stake in the project, including Malaysia’s Petronas, China National Petroleum Corporation, Japan’s Mitsubishi Group, and Korea Gas Corporation.[7] Of the C$40B, the four Asia Pacific investors combined contributed 60 percent, or C$24B, to the project. The investment will finance the construction of the LNG export terminal in Kitimat, a district municipality located approximately 1,450 km northwest of Vancouver, and is expected to create 10,000 jobs by 2021.[8]

On the other hand, BC outward investment into the Asia Pacific has been on the decline since 2004. The mining sector continued to lead outward investments into the Asia Pacific, accounting for nearly 30 percent of the province’s total investment in the region from 2003 to 2018. While the number of outward investment deals in the mining sector has increased slightly in the period between 2015 and 2018 (43 deals) relative to the period between 2011 and 2014 (39 deals), the investment values of these deals dropped by C$2.4B.

In comparison to the mining sector, growing interest among BC investors was seen in the software and computer services sector in the Asia Pacific from 2011 to 2018. BC outward investments in this sector increased by C$97M from the 2011 to 2014 period to the 2015 to 2018 period, while the number of investment deals have increased from 9 to 13. Singapore and Australia have emerged as the top two destinations for BC investments in this sector over the past four years. These companies cite growing client bases in the Asia Pacific region as the reason for their investment.[9] For instance, Colligo, a software company specializing in data synchronization solutions, invested close to C$31M in 2015 to open a new office in Melbourne so that the company could better serve its customers in the Asia Pacific region. Similarly, the Vancouver payment solution company Hyperwallet Systems invested C$8M to establish a marketing operation in Singapore. The company cited a growing customer base in the Asia Pacific region for its expansion.[10]

ALBERTA: THE RETURN OF OIL AND GAS JUST A PIPE DREAM?

Even though crude oil prices bottomed out in 2015, it appears that Alberta is still dealing with the after-effects of the oil price shock. Albertan two-way investment remains down across the board. Inward investments are at their lowest point since the Great Recession, while outward investments are at their lowest point since 2003. After controlling for the blockbuster C$15.2B deal between the China National Offshore Oil Corporation Ltd. and Calgary’s Nexen Inc. in February 2013, inward investments to Alberta from the Asia Pacific declined by nearly 80 percent in the period between 2015 and 2018 following continuous growth between 2003 and 2014.

Alberta’s recovery from the record low oil prices of 2015 appears to be slow but in progress, as the number of inward investments made in the province from the Asia Pacific have increased year by year since bottoming out in 2016. There were 16 investments in 2018, compared to only four investments in 2016. While the oil and gas sector continued to be the highest-valued sector for investments from the Asia Pacific, over the past two years Alberta saw more deals made in non-resources sectors relative to the resources sectors. In 2017, the province saw three deals in resources sectors and four deals in non-resources sectors. In 2018, these numbers jumped to 6 in resources sectors and 10 in non-resources sectors.

Growth in non-resources sectors in 2018 came from a rather unexpected source. In June, Australia-based Dementia Care Matters announced it would expand its business to Canada by opening five locations in Alberta and one in Ontario by the fall of the same year. The company provides training assistance to those caring for people with dementia through courses and the establishment of a community support group. With the number of Albertans aged 40 and older being diagnosed with dementia expected to rise three-fold in the next 30 years, Dementia Care Matters’ entry into Alberta will help provide caregivers the proper training needed to handle the rise in dementia cases.[11]

Outward investments by Alberta to the Asia Pacific since 2003 have been cyclical, with the Great Recession and the oil price shock of 2014 acting as turning points. The number of investment deals made and the value invested have both declined since 2014 and hit their lowest point in 2017, with only two deals going into the Asia Pacific valued at over C$13M. This again coincides with the declining oil prices prevalent during this time. Diversification away from oil and gas related investments appears to be more dramatic in this case relative to the inward investments Alberta experienced. Since 2017, Alberta only made seven investment deals in the Asia Pacific, valued at C$125M, and two of those seven deals were in the oil and gas sector, valued at C$8.5M. Both deals in the oil and gas sector occurred in 2018. The largest investment deal since 2017 came from Canadian Pacific, who opened an office in Shanghai. Canadian Pacific’s new office was valued at C$88M as announced in early 2018 and was designated the company’s Asian base as it looks to build up its business in the region.

While oil prices have rebounded from their lows in 2015, they still fall well below the highs seen earlier in the decade. It’s not clear if the Albertan economy can continue to weather oil prices at their current level, but increasing political tensions in major oil-producing countries like Venezuela, Libya, and Iran – along with the hastiness of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries cutting and raising oil production goals overnight – continue to raise the question of whether the province will ever see stable investments in oil and gas related projects. The incentives and opportunities for Alberta to diversify its investments have never been greater.

ONTARIO: SOUTHERN ONTARIO CONTINUES TO FUEL THE PROVINCE'S INVESTMENT ENGINE

Canada’s richest and most populated province continued its dominance as the top source province for Canadian investments into the Asia Pacific, and in the past three years it has overtaken Alberta as the number two Canadian destination for investments originating from the Asia Pacific as a result of declining investments in Alberta’s oil and gas sector. In terms of outbound investments to the Asia Pacific, Ontario has led all other provinces in both the number of deals brokered in the Asia Pacific and the amount invested. To put into perspective the province’s dominance in investments made in the Asia Pacific, Ontario’s C$129.8B exceeds the C$79.6B of total investments made by all the other provinces combined.

Inward investments from the Asia Pacific into Ontario have risen steadily since the recession years. Investments have been primarily in the automobile and parts sector owing to the strong manufacturing presence in the southern part of the province, totalling nearly C$2.4B since 2015. Investments in this sector had been trending downward since the recession; however, significant investments from major automotive manufacturers and parts makers like Japan’s Toyota Motor Corp. and Hong Kong’s Johnson Electric reversed this trend. Toyota’s investment of over C$2B since 2015 and Johnson Electric’s C$360M investment in December 2017 play against the rhetoric that manufacturing is on the decline in Ontario. [12]

2018 marked the 90th anniversary of diplomatic ties between Japan and Canada and the establishment of Japan’s diplomatic mission in Canada. Throughout these 90 years, Japan and Canada have enjoyed an amicable relationship, with Canada playing a major role in Japan’s economic recovery following the Second World War. Through numerous bilateral deals, Canada’s nomination of Japan to the United Nations and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the general receptivity of Japanese products by Canadians, among other factors, Japan was able to become the large and advanced economy it is today. Helping drive that growth was the establishment of large Japanese multinational companies.

Aichi-based Toyota Motor Corp. is one of those large multinational companies, and through its divisions Toyota and Lexus, it has maintained a presence in Southern Ontario since 1986 and has grown significantly since then. Toyota today operates four plants in Cambridge and Woodstock, Ontario, with an annual manufacturing capacity of 600,000 vehicles, while employing over 8,000 people. The two plants are noted for manufacturing the Corolla sedan and RAV4 sport utility vehicle, two of Toyota’s most popular models, along with Lexus’ best-selling RX sport utility vehicle. In May 2018, Toyota reaffirmed its commitment to Ontario and Canada by announcing that it will invest C$1.1B to upgrade its four plants for increased production of the RAV4, along with another C$200M over 10 years to support automotive research and development in Canada. At the announcement, Toyota Motor Manufacturing Canada president Fred Volf spoke about Toyota’s long-running relationship with the province of Ontario:

Ontario has always been a great home for Toyota Motor Manufacturing Canada. We benefit from investments in technology, innovation, and industry as well as the high-skilled workforce we’re fortunate to have as our team members. With our Ontario government partners, today we celebrate the results of our past 30 years of manufacturing in Canada, and continue on the path of building for our future.

Toyota’s announcement was a welcome sight to the province once considered the manufacturing hub for the automotive industry in North America. Changes to consumer tastes and the increasing access to cheap labour in Mexico via NAFTA and now CUSMA, along with rising trade nationalism in the United States, have forced companies to relocate manufacturing facilities further south. This sentiment was further underscored as General Motors decided to close to its plant in Oshawa, Ontario, at the end of 2019 and move four-door sedan and truck production to its plants in Indiana.

While Tokyo-based Honda Motor Co. Ltd. also established a manufacturing plant in Alliston, Ontario, around the same time as Toyota in 1986, other Japanese automakers have used Ontario as a base for parts manufacturing or have partnered with existing Canadian parts suppliers for their North American operations. Going forward, automakers are expected to invest heavily in research and development as the industry moves toward developing autonomous and electric vehicles.

While the automobile and parts sector outweighs all the other sectors for inward investments, significant growth was seen in the industrial engineering sector. While Ontario only saw four deals in this sector since 2015, these four deals combined were valued at nearly C$1.6B and worth over six times the investments made between 2011 and 2014. This sector, however, was led by a whale deal made between Aurora, Ontario-based Magna International Inc. and Hanon Systems of South Korea, valued at C$1.5B.

Outward investments from Ontario have been fairly diverse, with the real estate investment and financial services sectors leading in terms of value invested abroad. Investments in real estate in the Asia Pacific continued to rise, with deals totalling over C$10B over the past three years being led by Toronto-based CPPIB.

The CPPIB continued its reign as the leading investor based in Ontario. Since 2003, investments by the CPPIB into the Asia Pacific’s real estate sector made up nearly half of the total investments in the sector by Ontario-based companies, and in 2018 its investments made up 45 percent of Ontario’s total investments into the Asia Pacific that year. In July 2018, the CPPIB announced that it will invest C$817M in Chinese rental housing, thereby taking advantage of government measures looking to boost rental housing projects as ways to overcome housing shortages in China’s largest cities.[13]

Investments in the travel and leisure sector in the Asia Pacific have also been significant, totalling nearly C$13B since 2003. However, deals to the Asia Pacific in this sector have dropped off significantly, with the number of deals down to just nine, and the investment value down nearly 91 percent since 2014. Recent investments in this sector, however, have totalled C$85M since 2015 and have been concentrated in South and Southeast Asia, regions that are expected to be the drivers of economic growth within Asia in the coming years.[14] Tim Hortons, for example, successfully established its first location in the Philippines in 2017. This kicked off the company’s Asia expansion plan, which will see them take advantage of growing middle classes across the region. By 2018, Tim Hortons had expanded to 11 restaurants in the country, and it has its sights set on entering the Chinese market.

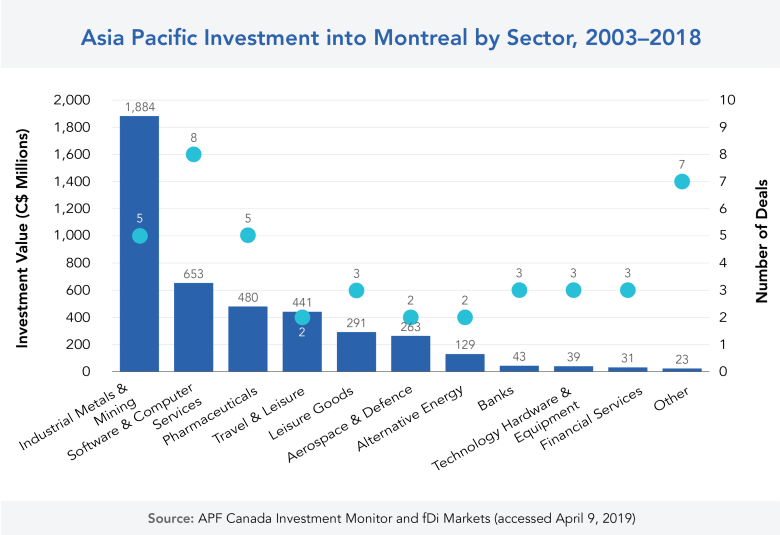

QUEBEC: STRIKING A TECHNOLOGY GOLDMINE

As Canada’s largest province by geographic area and the second-largest contributor to the country’s GDP, Quebec plays a crucial role in Canada’s economy. Historically, the province has ranked fourth for both inward and outward investments with the Asia Pacific in terms of investment amount, ranking behind Ontario, BC, and Alberta. However, when looking strictly at the time period between 2015 and 2018, Quebec managed to pass Alberta in terms of investments to the Asia Pacific, but now ranks behind the rest of Canada as an aggregate for investments from the Asia Pacific. The value of inward investments from the Asia Pacific are higher now than in the years before the recession; however, since 2014 investment values have trended downward slightly. Despite this, Quebec has been seeing an increase in investment deals following a decline during the Great Recession. Since 2015, Quebec has received 35 investment deals, exceeding the 28 deals Quebec saw prior to the recession.

The value of Quebec’s outward investments in the Asia Pacific took a hit around the recession years and have recovered slightly but are still below the values seen prior to the recession. Despite the decline in investment value, the number of investment deals made in the Asia Pacific between 2007 and 2014 had been stable, followed by a slight decline between 2015 and 2018.

The mining industry remains the dominant sector for investments to and from the province. Between 2003 and 2018, Quebec saw investments totalling C$3.7B into its mining sector from the Asia Pacific. The global demand for resources between 2011 and 2014 following the recession, combined with the Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions’ interventions from 2011 to 2016, have benefited Quebec’s natural resource-rich regions.[15] In 2014, there was a shift in inward mining investments in Quebec as companies focused more on mining of precious metals instead of iron and steel.

Quebec has also seen a growth in investment in its pharmaceutical and software and computer services sectors in the past four years by Asia-based multinational companies. For example, Montreal saw investments from Japan’s Mitsubishi Group in a C$391M acquisition of Medicago in 2013, and from South Korea’s Green Cross through a C$333M deal in 2017 to open its first North American plant. Quebec’s pharmaceutical sector accounts for 15 percent of Quebec’s total inward investments, valued at C$1.2B. Quebec’s software and computer sector saw investments from Japan’s Fujitsu Global and Sony Corporation along with South Korea’s Samsung Group. These are major players who are breaking into Quebec’s technology sector, which has seen nearly C$700M in investments since 2003 in areas such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and self-driving technologies. With the increase in the number of outward investment deals combined with Quebec’s booming knowledge economy and world-class research institutions, Quebec was selected to lead the AI-powered supply chain supercluster in Canada.[16]

While Toronto is known as Canada’s financial capital and Calgary as Canada’s oil capital, Quebec has been establishing itself as a hub for the pharmaceutical and life sciences industry. Southeastern Quebec has been home to companies and research centres who have benefited from easy access to a highly skilled workforce along with investment incentives from the province of Quebec. A blip in the industry following the 2008 recession led to some centres closing or laying off staff. In 2012, industry giants Sanofi and Johnson & Johnson laid off 226 people in an industry that at the time had already lost nearly 3,000 jobs since 2006 despite the Quebec’s government continued support of the industry through incentives. However, this downturn in the industry did not seem to affect investments coming from Asia, as Quebec saw more investments in its pharmaceutical sector in the five years following the 2008 recession compared to the five years before the recession, capped off by an investment by Japanese multinational corporation Mitsubishi Group.

Mitsubishi Group, through its subsidiary Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp., acquired a 60 percent stake in Quebec City-based Medicago in a deal just shy of C$400M. While other companies were looking for ways to downsize and streamline operations, Medicago viewed this investment as an opportunity to “foster the development of innovative vaccines with the financial stability to expand our Quebec, Canadian, US, and global operations,” according to CEO Andy Sheldon. Karnataka-based Strides Pharma Global Private Limited has also maintained a presence in the southern Quebec region through a joint venture in 2012 with Jamp Pharma and an acquisition of Pharmapar in 2018 from KDA.

Going forward, Quebec remains committed in its support of the pharmaceutical sector. In 2017, the province introduced the Quebec Life Sciences Strategy, which set aside C$205M to help increase investments in research and innovation in the life sciences sector, to foster creation of innovating companies, to attract new private investments, and to promote the greater role innovation will play in the health and social services network. Through this strategy, the province hopes to attract C$4B in private investments by 2022 and to be one of North America’s top five life sciences hubs by 2027.

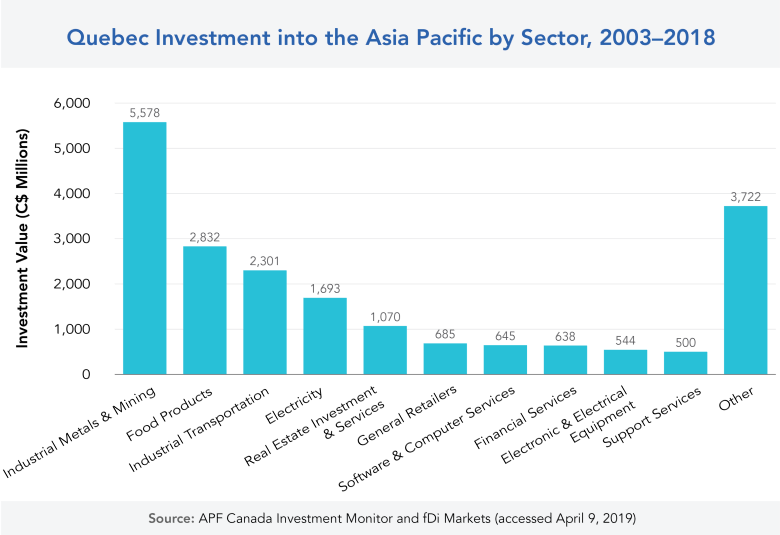

Similarly, much of Quebec’s outward investments into the Asia Pacific from 2003 to 2018 was in the mining sector, which saw approximately C$5.6B in investment overall. China, South Korea, and Australia were key investment destinations in this sector. Outside of mining, Quebec’s food production, industrial transportation, and real estate sectors have seen growing investment outflows. Since the 2009 recession, investments in these three sectors combined rival the investments made in the mining sector at C$5.1B and accounted for almost over 60 percent of Quebec’s outward investments since then. The largest investment in the food production sector coming out of Quebec occurred in 2018, when Montreal-based Saputo Inc. acquired Murray Goulburn, a major Australia-based dairy co-operative, in a blockbuster deal worth nearly C$1.3B. Following this deal, Saputo became the first and largest foreign-owned company in Australian dairy history and the largest investment in the Asia Pacific by a Quebec-based company in a non-resources-related sector.

REST OF CANADA: INVESTMENTS FEW AND FAR BETWEEN

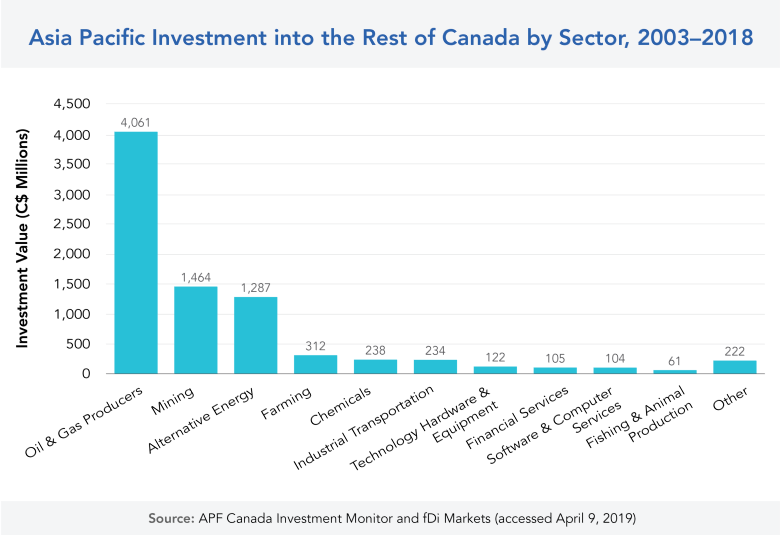

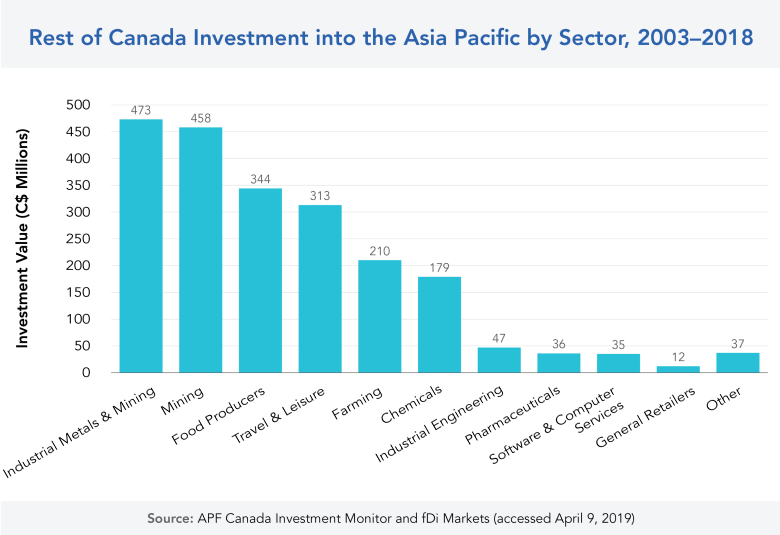

A notable characteristic regarding the investment ties between the rest of Canada and the Asia Pacific for the past 16 years is that most of the provinces and territories have seen very few investment deals go to and originate from Asia. In fact, the rest of Canada combined made up only 1 percent of Canada’s total outward investment deals and received only 7 percent of the Asia Pacific’s investments into Canada. Australia, China, and India were the most common destinations for investments to the Asia Pacific, while the bulk of investments from the Asia Pacific have been concentrated in Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Inward investments from the Asia Pacific into the rest of Canada have been scattered with no discernible growth nor decline. Oil and gas remained the largest sector for inward Asia Pacific investment from 2003 to 2018, and it accounted for nearly half of all total inward investments into these provinces.

In Atlantic Canada, New Brunswick saw its largest investment from the Asia Pacific in 2018 when India-based information technology company Mahindra Group invested C$119M to establish a new business services centre. The new centre is expected to create up to 116 jobs in the next five years.[17]

Newfoundland and Labrador saw a surge of inbound investment in the province’s oil and gas sector. The surge was driven by a transaction in 2017, when Husky Energy, a subsidiary of the Hong Kong conglomerate CK Hutchison Holding Ltd., invested C$2.2B in an offshore oil drilling project. According to the company, the project will create approximately 250 jobs on the new oil platform and indirect employment for 1,500 people.[18]

Nova Scotia also saw an increase of inbound investment in the industrial transportation sector. The growth was attributed to an investment by Nippon Express, a Japanese logistical solution company that opened a new office in Halifax in July 2018 in a C$20M investment. As further increases in the volume for sea and air cargo in Halifax are anticipated, the company established the new office to provide better service to companies in the fishery products industry.

The territories did not make any investments in the Asia Pacific and received over half of a percent of the Asia Pacific’s investments in Canada. The territories played to strength in the investments it received as all were in the mining sector and originating from either Australia or China. The last investment made in the region occurred in the Yukon in 2014 in a joint venture with a BC-based company looking into the feasibility of the Carmacks Copper-Gold-Silver project located 220 km north of Whitehorse.

Outward investments from the rest of Canada into the Asia Pacific were valued at C$382M between 2015 and 2018, a nearly 50 percent drop from the C$693M invested between 2011 and 2014. The industrial metals and mining sectors continued to attract the greatest investment interest into the Asia Pacific. However, both sectors have not seen any outward investment activity within the past four years. In contrast, recent outward investments into the Asia Pacific have occurred in other sectors, such as health care equipment and services and other non-resources-based sectors.

Another interesting investment deal came in 2018 when Acadian Seaplants, a Nova Scotian company specializing in biostimulant and bionutritional solutions, established an Indian subsidiary and opened a processing facility in Vadodara, India. Through this investment, the company hoped to better meet the needs of the local farm owners with the new subsidiary and facility in an investment valued at C$36M.[19]

[6] Industry Canada. Trade Data Online. https://www.ic.gc.ca/app/scr/tdst/tdo/crtr html?timePeriod=10%7CComplete+Years&reportType=TE&searchType=All&productType=HS6¤cy=CDN&countryList=specific&runReport=true&grouped=GROUPED&toFromCountry=CDN&areaCodes=R994&naArea=9998

[7] LNG Canada. LNG Canada Export Terminal. https://www.bcogc.ca/node/11289/download

[8] CBC. B.C. Workforce Ready to Take Advantage of 10,000 LNG Jobs, Says Trades Council. October 4, 2018. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/b-c-workforce-ready-to-take-advantage-of-10-000-lng-jobs-says-trades-council-1.4849179

[9] T-Net. Colligo Selects Melbourne, Australia for Australasia Expansion. https://www.bctechnology.com/news/2015/10/27/Colligo-Selects-Melbourne-Australia-for-Australasia-Expansion.cfm

[10] Hyperwallet Systems Inc. Hyperwallet Continues Global Growth With Opening of its APAC Headquarters in Sydney, Australia. https://www.hyperwallet.com/news-announcements/hyperwallet-continues-global-growth-opening-apac-headquarters-sydney-australia/

[11] Alberta Health Services. Population Estimates of Dementia in Alberta. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/about/scn/ahs-scn-srs-addma-2016-peda-update.pdf