Foreword

MESSAGE FROM STEWART BECK, PRESIDENT AND CEO, APF CANADA

The increasing significance of Asia as the driver of the new global economy underscores the need for Canada to strategically deepen and diversify its investment relationships in the region, which is a fast-changing, complex and increasingly competitive environment. The timing for Canada to seek and solidify new economic partnerships in the Asia Pacific could not be better. As legacy relationships continue to strain under the wave of isolationist, anti-trade rhetoric that has been sweeping the U.S. and Europe, Canada is receiving renewed attention for its social and economic openness, transparent business culture, and good governance.

The economies of the Asia Pacific present unique opportunities for Canadian foreign direct investment into the region, but a lack of detailed information tracking the types and volume of Asia-directed FDI can negatively impact both Canada’s public discourse and its policy development – and ultimately contribute to a lack of understanding about the implications for the Canadian economy and on Canadian employment.

Last year, the Investment Monitor tracked Asia Pacific investment in Canada; this year it turns its attention to Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific. (In its third year (2019), the Investment Monitor will focus on two-way investments between cities).

There are many informative and useful takeaways in this year’s data-tracking, as you will see from the pages of this annual report. Two outbound FDI trends in particular resonated with me: Canada’s investment focus on the fast-growing consumer economy of India and the rapidly developing markets of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, as well as the increasing presence of Canadian state-owned enterprises, or Crown corporations, in Asia Pacific markets – an FDI flow that between 2013 and 2017 accounted for a quarter of all Canadian investment in the region.

These two trends indicate that Canada is awakening to the rapid growth and expanding markets in South and Southeast Asia. They also demonstrate Canada’s willingness – and ability – to build stronger investment ties among the diverse economies that make up the larger Asia Pacific region, which in the long-term will improve Canada’s market access in economies where our competitors have already established strong investment footholds.

Canadian FDI into the Asia Pacific will help foster wider economic engagement with the region. It is our hope that this year-two report will highlight new trends and opportunities for Canadian firms looking to do business in the dynamic markets of the Asia Pacific.

On behalf of APF Canada, I would like to acknowledge the efforts of those involved in producing this report. I would first like to thank our partner, The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary, and our sponsors, the Bank of Canada, Export Development Canada, the Government of British Columbia, and AdvantageBC.

Second, I would like to extent my appreciation to our Advisory Council members, Eugene Beaulieu, Kelly Best, Kursti Calder, Colin Hansen, Lori Rennison, Stephen Tapp, and Claudia Verno for the feedback they have provided in the process of developing this report.

And finally, I would like to thank the APF Canada research staff who were responsible for writing and finalizing this report, Eva Busza, Vice-President, Research and Programs, Justin Elavathil, Program Manager, Trade, Investment and Innovation, Pauline Stern, Project Specialist, Trade and Investment, our Junior Research Fellows and intern, Denea Bascombe, Stephanie Fraser, Jonathan Wilkinson, and Martin Cheuk Kwan Chan, and APF Canada’s communications team for editing and designing the final publication, Michael Roberts, Communications Manager, and Anna Djerfi, Graphic Designer.

Stewart Beck, President and CEO, Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada

Executive Summary

The Asia Pacific is home to many of the world’s most dynamic and fastest-growing economies, and boasts unprecedented opportunities for foreign investment in a number of key markets. While there is anecdotal evidence to suggest that Canadian investors are dipping their toes into Asian markets, a lack of reliable public data makes it difficult to determine the volume, scale, or scope of Canadian investment in the region. In order to address this gap, the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) partnered with the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary to create the APF Canada Investment Monitor, a database and interactive web-based tool that tracks investment ties between Canada and the Asia Pacific at the enterprise level.

The APF Canada Investment Monitor aggregates raw data from APF Canada’s archive of investment deal announcements from 2003 to present (see methodology section for further details). Each year of the three-year project corresponds with an annual theme: year one is on Asia Pacific investment in Canada (published April 2017), year two is on Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific (April 2018), and year three is on two-way investment ties between cities (April 2019).

Data from the APF Canada Investment Monitor shows that Canadian investment into the Asia Pacific has been characterized by intermittent spurts of activity and by substantial shifts in both geography and sectoral focus between 2003 and 2017. Over the past decade and a half, Canadian investors have predominantly focused on opportunities in Australia, China, and India. Together, these economies capture 60 percent of all investment outflow from Canada into the Asia Pacific.

One of the key findings is that, despite a growing number of Canadian investments in China from 2003 to 2010, investment values have been declining since 2008. Most of the Canadian investment in China has been in the financial sector, which includes investment services, consumer finance, and real estate. Australia has been a consistently popular destination for Canadian investment over the past 15 years, with the volume and scale of investments steadily rising since 2013. Investment has been mainly in the natural resources sector, with a specific focus on oil and gold mining companies. Although the volume of Canadian investment in India has varied significantly from year to year, investment into consumer-driven sectors has been on the upswing since 2010 as Canadian firms position themselves to capitalize on India’s projected consumption growth in coming years.

In more recent years, there has been a definite increase of investment interest in the developing markets of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Taken as a singular unit, these countries account for 18 percent of all Canadian investment value into the Asia Pacific region from 2003 to 2017.

The changing geographic focus has been coupled with changes in the types of companies that Canadian firms are investing in as well as the investment partnership structure of the deals. Prior to 2013, Canadians focused on greenfield investments. However, in the past 15 years, investors have given increased support to mergers and acquisitions. As a consequence, from 2013 to 2017 the value of Canadian investments in merger-and-acquisition deals was greater than greenfield deals. Along similar lines, while the majority of investment over the years has been made by privately owned enterprises, Canadian state-owned enterprises, or Crown corporations, have been increasing their presence in Asia Pacific markets. Their investment in the region grew substantially between 2013 and 2017 and accounted for a quarter of all Canadian investment value in the Asia Pacific.

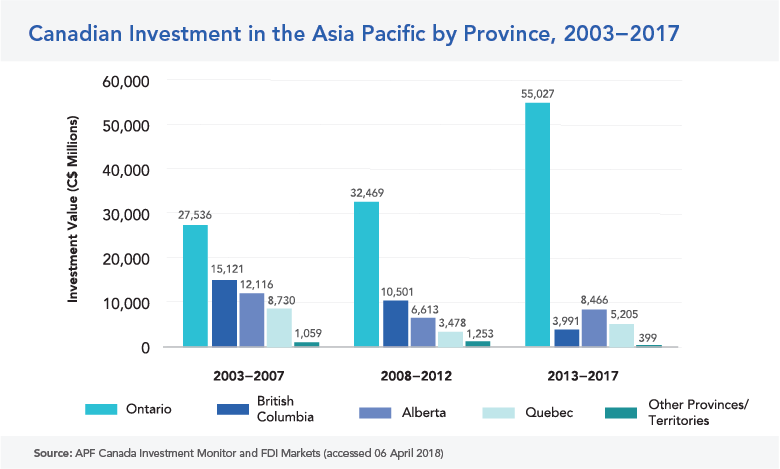

At the provincial level, investors from Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, and Quebec were the most active in Asia Pacific markets. Investors from Ontario focused their investment on financial and transport services, investors from British Columbia and Quebec focused their investment on mining, and investors from Alberta focused their investment on energy. While investors from Canada’s other provinces made noticeable investments in mining between 2005 and 2012, these provinces drastically lagged behind the rest of the country in outward investment overall. However, an increase in investments in consumer goods and services has forged a way for Canada’s smaller provinces to find their own path in the Asia Pacific.

Although Canada’s investment profile within the Asia Pacific has grown moderately over the past 15 years, the country’s overall share of investment in the region has fallen behind many of its competitors. Canada needs to continue to leverage its strengths and build stronger ties with the region in the future in order to improve market access and position itself as an important investor in the diverse economies that make up the Asia Pacific.

Introduction

ASIA IS A GROWING HUB OF GLOBAL INVESTMENT

The Asia Pacific is fast becoming the hub of the global economy, both as a source and destination of investment. In 2016 alone, the Asia Pacific accounted for approximately C$600B in global investment outflow, or 31 percent of the global total outflow, and C$590B of global investment inflow, or 26 percent of the global total inflow.[1][2]

Cross-border investment can generally be broken down into two categories (not including foreign aid): 1) foreign direct investment (FDI) and 2) foreign portfolio investment (FPI) (see Box 1 for definitions). FDI is more growth focused, as it is considered a long-term relationship tied with technology and knowledge transfers and access to new talent and markets.[3] FPI is considered short-term, as the flow of investment reacts quickly to changes in the market.

In Canada, the narrative surrounding Asia’s growing importance in global investment has mainly focused on the implications of greater inward FDI from the Asia Pacific into Canada. APF Canada surveys have shown that the Canadian public doesn’t have a strong understanding of the country’s FDI ties with the Asia Pacific and the potential benefits that may accrue to the Canadian economy from these investments.[4] This lack of understanding has in all likelihood contributed to the negative attitudes that Canadians have toward certain Asian investment.

There tends to be much less discussion of the reverse flow: Asia-bound Canadian investments. Studies show outward FDI is sometimes viewed as having a negative impact on the domestic economy as it is a decrease in domestic capital stock.[5] What is less well known are the many positive effects that the outflow can have. Benefits of outward FDI for the Canadian economy can include enhancing exports by creating more demand for goods and services, acquiring more technology for use at home, and repatriation of profits, among others.[6]

As a key and growing market for Canadian outward FDI, understanding the impact of our investment in the Asia Pacific is important for Canadians.

THE CHALLENGES OF INVESTING IN THE ASIA PACIFIC

While the Asia Pacific is often described as a monolithic entity, Canadian companies investing abroad are beginning to understand that the region is not a single economic bloc, but a collection of different economies that present unique investment opportunities and challenges.

Canadian investors are benefiting from Canada’s trade and investment agreements with partners in the region, in the form of Canada’s bilateral investment treaties (also known as foreign investment promotion and protection agreements, or FIPAs) and free trade agreements with investment provisions. Of Canada’s six agreements in force with partners in the region, five are FIPAs (China, Hong Kong, Mongolia, the Philippines, and Thailand) and one is a free trade agreement (South Korea). In addition to these agreements is the recently signed, but not yet in force, multilateral free trade agreement named the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). While these agreements provide a clearer understanding of the regulations and treatment of investment in each party’s jurisdiction, historically they have not necessarily given rise to greater investment flows nor guaranteed good returns on investments.

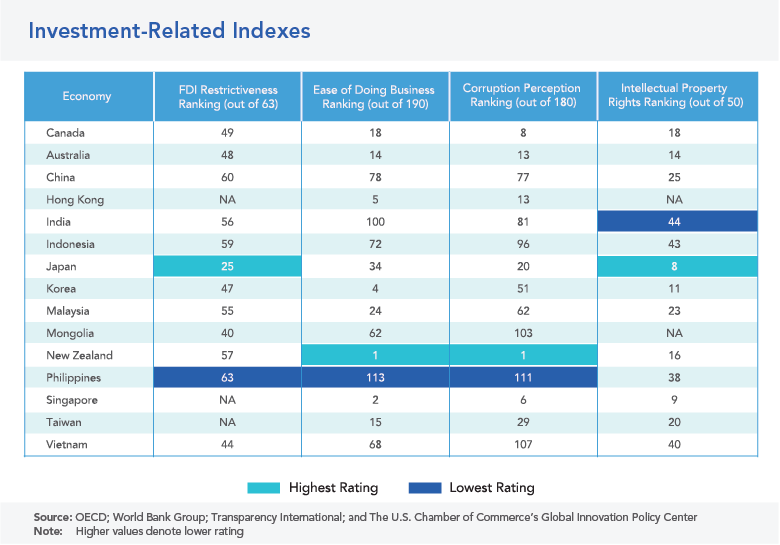

Important factors that affect business decisions on where to invest in the region include different economies’ openness to FDI, ease of doing business, political stability, corruption levels, and intellectual property protection rights, among others. The regulations that govern investment and business in each economy are quite different from jurisdiction to jurisdiction (see Table 1). For example, an economy like the Philippines scores poorly when it comes to letting in FDI and levels of corruption, which in turn also leads to a difficult business climate to work in. On the other hand, New Zealand scores extremely well in terms of low levels of corruption and high intellectual property rights protection, leading to the highest score in terms of ease of doing business.

WHAT OUR OFFICIAL STATISTICS CANNOT TELL US

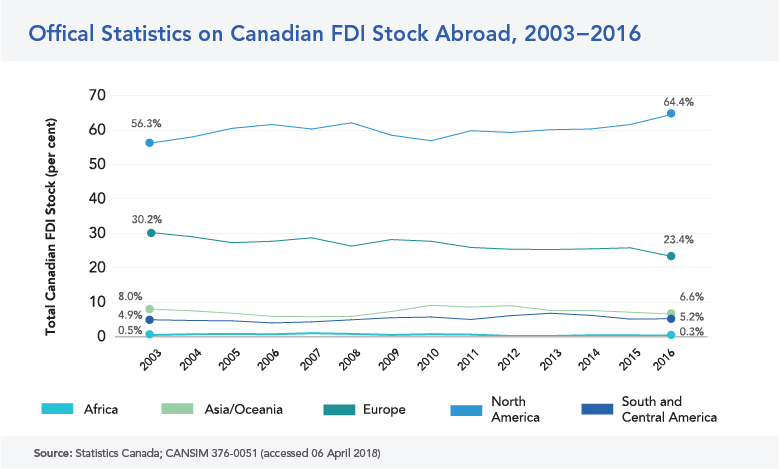

Canadian official statistics show that from 2003 to 2016, Canadian investment stock, or the total value of assets in an economy at a period of time, in the Asia Pacific (Asia/Oceania and including the Middle East) rose from approximately C$33B to C$69B. Despite the increase over the years, the Asia Pacific region’s share in Canada’s outward FDI stock has remained relatively low and stable, averaging 7 percent over the period and never going over 9.1 percent or lower than 5.8 percent.

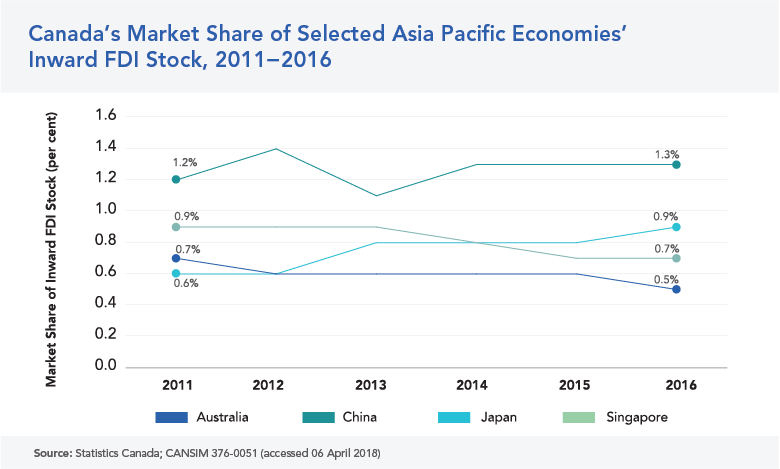

Data from the official statistics bureaus in Australia, China, Japan, and Singapore also show that Canada’s market share of their economies’ inward investment has basically plateaued over the past six years, hovering at less than one percent on average.

Due to a variety of reasons, official statistics do not paint a complete picture of Canadian foreign direct investment in the Asia Pacific. Official statistics do not provide many key pieces of data such as detailed information regarding investment flows to all economies, subnational data, industry breakdowns by economy, and ultimate investors and beneficiaries. A recent report released by Statistics Canada showed the stark differences when official statistics try to account for the ultimate investor.[7] In the case of China, tracking the ultimate investor leads to a two-fold difference in uncaptured investment. This is because investments catalogued under the current methodology used by Statistics Canada cannot account for investments that are routed through third-party economies, such as the Cayman Islands.

INVESTMENT MONITOR FILLS THE GAP

In response to the need for more complete data on the two-way flow of investment between Canada and the Asia Pacific, APF Canada, in partnership with the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary, developed its Investment Monitor. With the launch of the APF Canada Investment Monitor website and first annual report in April 2017 APF Canada has started to fill the gap left by official statistics investment data, revealing previously unknown trends in Canada’s two-way investment relations in the Asia Pacific.Last year’s inaugural annual report focused on investment from the Asia Pacific in Canada, providing trends in the destination of investments from a Canadian national perspective and a Canadian provincial perspective, as well as the sources of investment from an Asia Pacific national perspective.

BOX 1. CROSS-BORDER INVESTMENT AND FDI

Cross-border investments can be separated into two major groups: 1) foreign portfolio investment (FPI) and 2) foreign direct investment (FDI).

1) FPI is considered a temporary investment by a resident or enterprise of one economy into a financial asset of another economy. This investment involves a non-controlling stake in an enterprise in the form of equity and/or debt securities as well as loans. For example, a resident of Australia buying shares of stock on the Toronto Stock Exchange would be considered FPI.

2) FDI is defined as a long-term or lasting-interest investment by a resident or enterprise of one economy into a tangible asset of another country. This type of investment is deemed to be “long-term” or of “lasting interest” if it is either a greenfield investment or an acquisition of at least 10 percent of the equity or voting shares of an enterprise. This 10 percent threshold is considered a controlling interest in an enterprise and is what primarily distinguishes FDI from portfolio investment, since it usually coincides with a transfer of management, technology, and organizational skills along with capital. For example, a Japanese firm buying a 20 percent stake in a Canadian pulp mill would be considered FDI.

Source: APF Canada Investment Monitor

[1] UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2017.

[2] Refers to foreign direct investment.

[3] Daude and Fratzscher. The Pecking Order of Cross-Border Investment. European Central Bank Working Paper Series No. 590, February 2006.

[4] Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2015 National Opinion Poll: Canadian Views on Asian Investment.

[5] Feldstein. The Effects of Outbound Foreign Direct Investment on the Domestic Capital Stock. National Bureau of Economic Research, March 1994.

[6] Kim. Effects of Outward Foreign Direct Investment on Home Country Performance. Korea Development Institute, July 1998.

[7] Atkins and Roesler. Foreign Direct Investment in Canada by Ultimate Investing Country. Statistics Canada, October 2017.

The National Picture

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The value of Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific is rising, but the number of investments has consolidated into fewer and larger deals.

- The two main investment trends are: 1) Canadian investment in natural resources, and 2) Canadian investment in companies that are targeting middle class consumers.

- Canadian SOEs are accounting for an increasing share of all of Canada’s investment in the Asia Pacific.

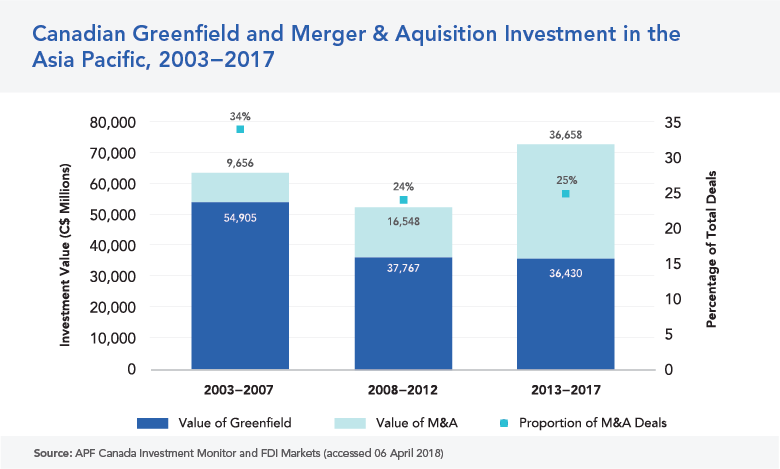

- Canadian investors are shifting their mode of entry from greenfield to M&A investments.

CANADIAN INVESTMENT IN THE ASIA PACIFIC IS CONSISTENT, BUT INCREASING IN FOCUS

Over the past 15 years, Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific has been shifting in both geographic and sectoral focus. Covering the period from 2003 to 2017, the APF Canada Investment Monitor has captured C$192B of investment 2,073 deals by 1,098 Canadian companies in 27 Asia Pacific economies.[8] The Investment Monitor reveals the depth and breadth of Canada’s economic ties in the region and highlights the inherent complexity of analyzing trends across such dynamic economies. As is true of much of global FDI flows, Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific is characterized by intermittent bursts of significant activity, mainly driven by a few large multinational corporations. This results in large differences in year-to-year investment flows.

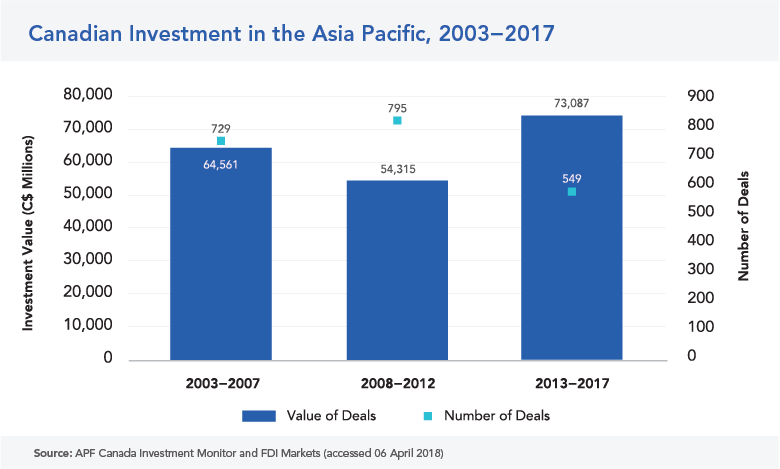

Over the past 15 years, the value of Canadian investment flows in the Asia Pacific has remained fairly stable.[9] During 2008 to 2012, the cumulative value dipped to C$54.3B from $64.6B in 2003 to 2007, but has since rebounded in 2013 to 2017 to reach C$73.1B. Although the investment flow value decreased during the financial crisis (2008 to 2012), the volume of deals during this time period – 795 – was the highest of the three periods, compared with 729 deals in the previous period and 549 deals in the period after.

NATURAL RESOURCES AND CONSUMERS ARE THE MAIN FOCUS

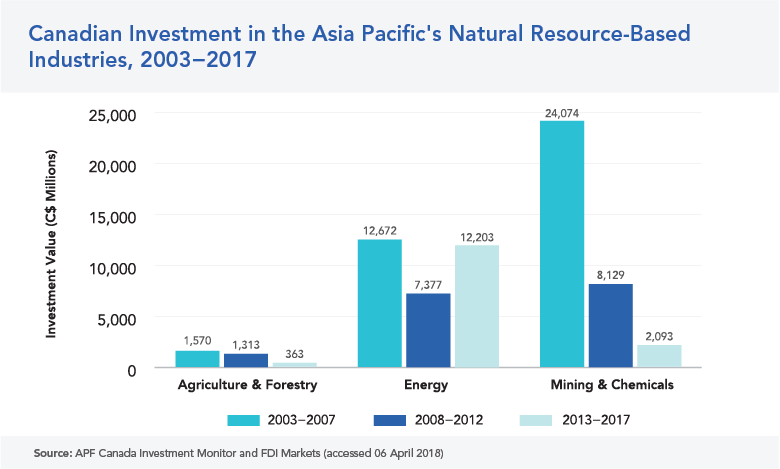

There are two distinct patterns of investment for Canadian companies in the Asia Pacific. The first is Canadian investment in natural-resource-based industries, which is the defining characteristic of the Canada-Australia investment relationship. The second pattern is focused on investing in companies that are targeting the growing needs and desires of the burgeoning middle class, such as in India and China.[10]

Natural-resource-based industries, including agriculture and forestry, mining and chemicals, and energy, are an important focus for Canadian companies in many Asia Pacific economies. They play a particularly prominent role in Australia, Mongolia, and Indonesia. The focus on natural resources at times is reciprocal, with multinational corporations from countries such as Australia and China making multiple large investments in Canada’s natural resources sector as well. In fact, Canada’s inward natural resources investment relationship with the Asia Pacific is even larger than its outward investment relationship – with Asia Pacific-based companies investing even more in Canada’s natural resources sector than vice versa.

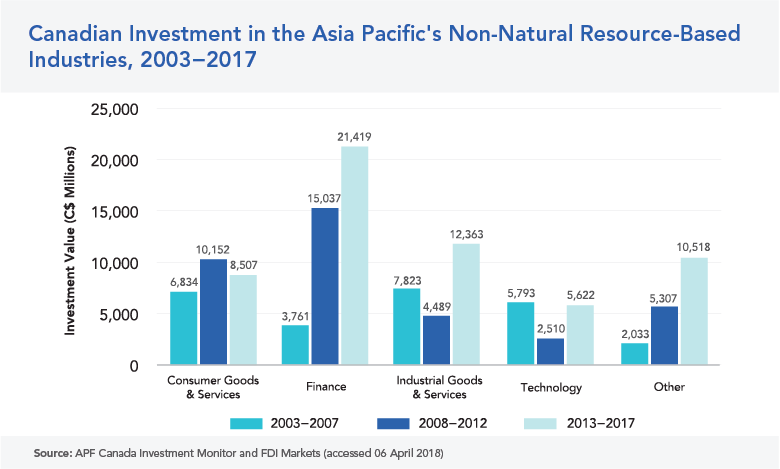

The second trend is that Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific is focused on industries and services that are targeting the growing global middle class in the region. Investments tend to be clustered in two non-natural-resource-based industries: finance, and industrial goods and services. When it comes to finance, 34 percent of all Canadian investment value in the industry is focused on the real estate sector and 49 percent is focused on the retail banking and investment services sectors. With respect to investment in industrial goods and services, the largest target of Canadian investment is logistics services, accounting for 50 percent of all investment in industrial goods and services.

CANADIAN STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES ARE EMERGING AS VEHICLES FOR ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENT

Canadians are often wary about Asia Pacific state-owned enterprise (SOE) investment in Canada;[11] however, lack of news coverage on Canadian SOE,[12] or Crown corporation, investment in foreign countries indicates that Canadians may not be as concerned about this kind of investment. An enterprise is considered state-controlled, if a national or subnational government has a controlling interest in the invested company. This controlling interest can result from the government either being the single largest shareholder of a company or by having 10 percent or more of the voting power.[13]

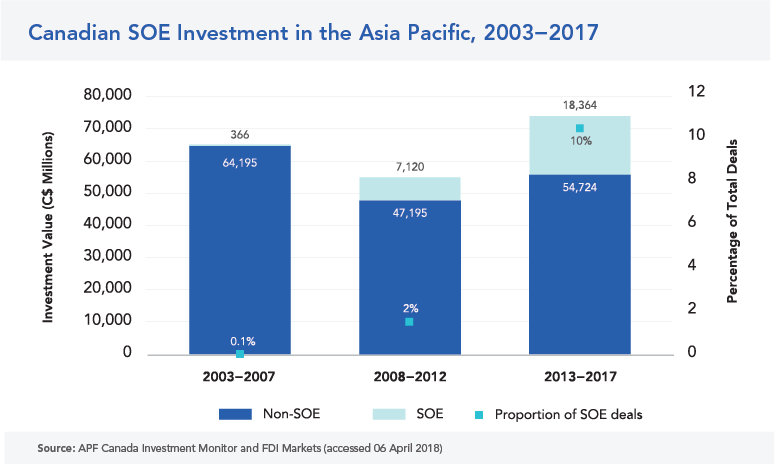

Over the past five years, Canadian SOE investment in the Asia Pacific has been growing. While it is nowhere near as high as the scale of Asia Pacific SOE investment in Canada, from 2003 to 2017 Canadian SOE investment in the Asia Pacific accounted for 13 percent of all Canadian investment value in the region.[14] Between 2013 and 2017, Crown corporation investment accounted for a quarter of all Canadian investment value in the Asia Pacific for that period. In terms of the proportion of deals, Canadian SOE investment made up 0.1 per cent of all deals from 2003 to 2007, while from 2013 to 2017 this amount grew to 10 per cent.

BOX 2. CANADIAN PENSION FUNDS LEADING THE WAY

Canadian millennials still have a long way to go before retirement, but they can enjoy peace of mind knowing that Canada’s largest pension funds are fixing their gaze on the Asia Pacific to fund the beachfront retirement dreams of today’s workers.

Over the period of 2003 to 2017, Canadian pension funds invested C$25B in the Asia Pacific. The top three – the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan Board, and the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec – accounted for 73, 13, and 10 percent of all pension fund investment in the region, respectively.

This new and growing focus by Canadian pension funds has two important implications: 1) it means that Canadians’ retirement financing is increasingly tied to the large and growing economies in the Asia Pacific, and 2) it means that Canada’s state-owned pension funds are becoming a major direct investor in the region.

The pension funds are focusing their investments on key markets that contain an increasingly large share of the world’s middle class consumers, such as India and China. As consumption grows in the world’s two most populous countries, the bottom line of Canadians’ retirement packages may benefit from the increased performance of the pension fund investments in these economies.

At the same time, Canadian pension fund investments are also providing necessary capital to help facilitate growth in key sectors in Asia. Investments in sectors such as real estate and logistics are currently the way in which these pension funds are tapping into these high-growth markets.

It looks like, at least for the immediate future, tying Canadian pensions to Asia is paying dividends on both sides of the Pacific.

VALUE OF MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS ARE ON THE RISE

In terms of the type of investments, over the 2003 to 2017 period, Canadian FDI into the Asia Pacific has seen a dramatic shift from greenfield investments to mergers and acquisitions (M&A) (see definitions in Box 3). Whereas between 2003 and 2012, the vast majority of investment value was executed via greenfield investment, in 2013 to 2017 the share of capital being invested in M&A overtook greenfield, accounting for 50.2 percent and 49.8 percent of investment value, respectively. However, when looking at the volume of deals, greenfield investment has been the most popular mode of entry for the past 15 years.

BOX 3. TYPES OF CROSS-BORDER INVESTMENTS

Foreign direct investments can generally be broken down into two categories: 1) greenfield, and 2) mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

GREENFIELD

A greenfield investment is an investment from a company in a new venture outside its own economy that results in the construction of a new facility (such as distribution hubs, production factories, offices, and/or living quarters) or an expansion upon such an initial investment. The advantage of greenfield investments is the ability to create a new facility that can be designed to meet current and future needs at reduced initial maintenance costs, while the disadvantages are the possible long startup times, high initial capital investment, and difficulties in securing a location for new facilities and hiring new staff.

MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS

An M&A investment is an investment in an existing company through acquiring a significant number of shares. The advantage of M&A investments is the ability to take over partial or total ownership of an existing facility immediately, with reduced initial capital investment and little need to hire new staff, whereas the disadvantages lie in possible long-term high maintenance costs, inefficiencies in current production methods, and suboptimal location.

Source: APF Canada Investment Monitor

[8] While this report covers the years 2003 to 2017, the APF Canada Investment Monitor project is ongoing and more recent figures can be found at investmentmonitor.ca.

[9] The report groups investment into three five-year time periods which help visually consolidate year-on-year trends: 1) 2003 to 2007; 2) 2008 to 2012; and 3) 2013 to 2017. This categorization has the further added benefit in separating out the global financial crisis (2008 to 2012) and its impact on global investment. When a historical analysis is not required, the whole data set from 2003 to 2017 is used.The report groups investment into three five-year time periods which help visually consolidate year-on-year trends: 1) 2003 to 2007; 2) 2008 to 2012; and 3) 2013 to 2017. This categorization has the further added benefit in separating out the global financial crisis (2008 to 2012) and its impact on global investment. When a historical analysis is not required, the whole data set from 2003 to 2017 is used.

[10] Please note that the financial bar for inclusion in the “global middle class” is significantly lower than that for the “Canadian middle class”.

[11] Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2015 National Opinion Poll: Canadian Views on Asian Investment.

[12] Included in the definition of Canadian SOEs are both federal and provincial Crown corporations. Prominent examples of Canadian SOE investors in the Asia Pacific include the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, and the University of British Columbia.

[13] This definition is similar to the one used by UNCTAD (2011).

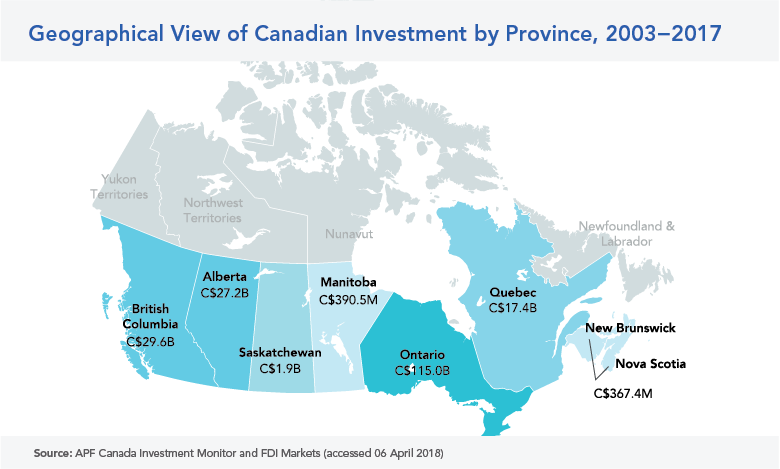

The Provincial Picture

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

- Provinces with the largest economies and biggest share of the country’s GDP – Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, and Quebec – invest the most in the Asia Pacific.

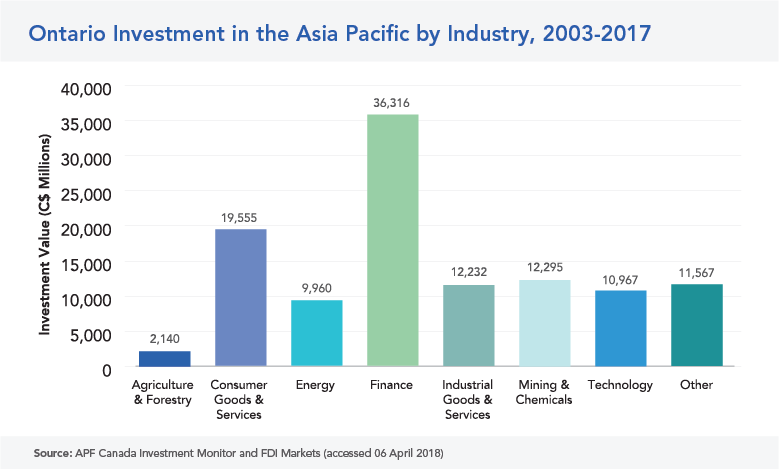

- Investments from Ontario are focused on financial services.

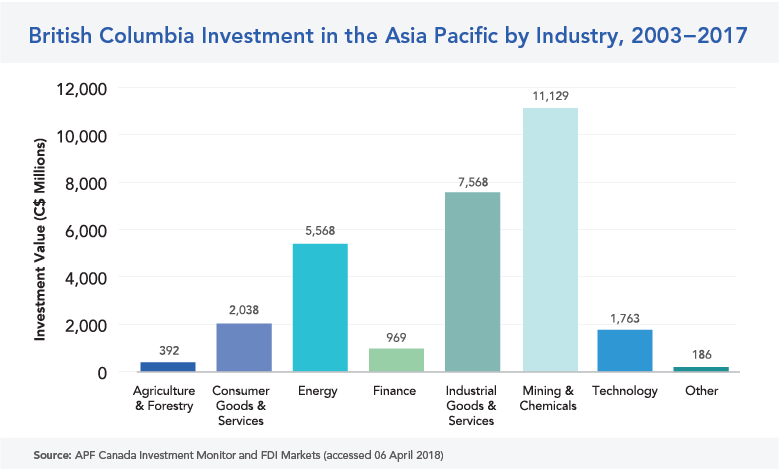

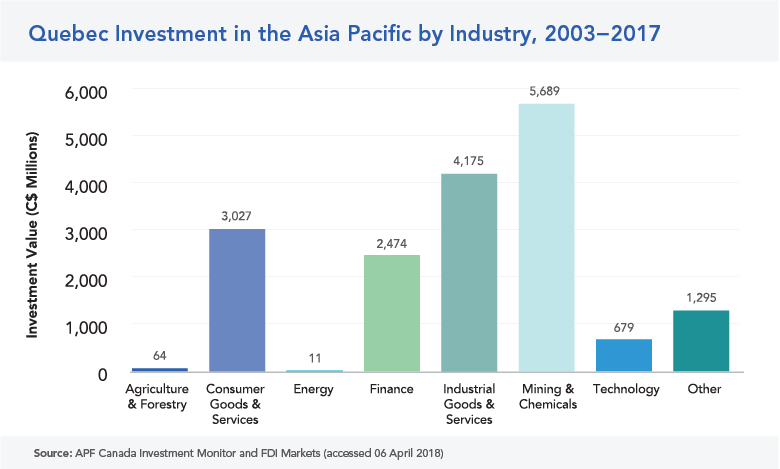

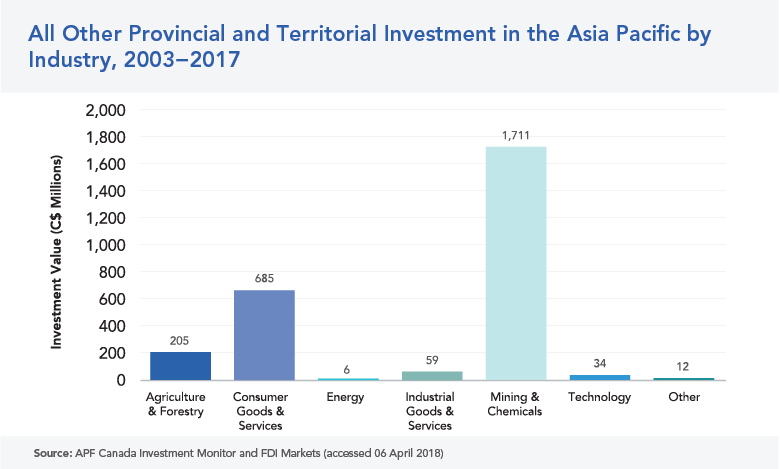

- Investments from British Columbia, Quebec, and the rest of Canada are focused on mining and chemicals.

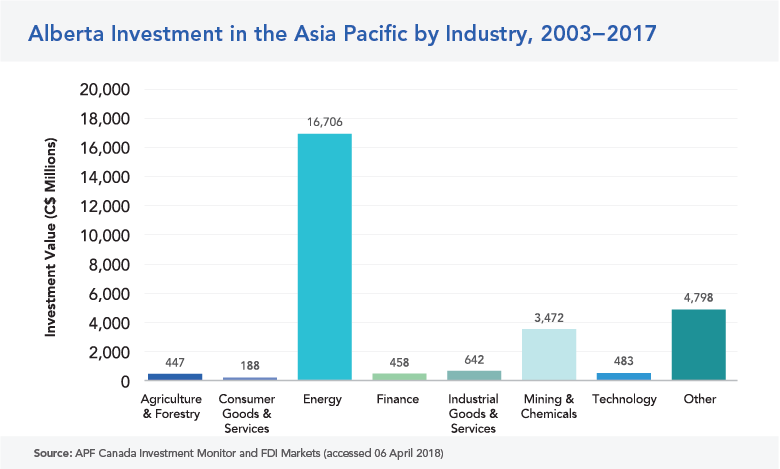

- Investments from Alberta are focused on the energy sector.

- Investments from the rest of Canada that focused previously on natural-resource-based industries are now pivoting more to consumer goods and services.

CANADA'S PROVINCIAL HEAVYWEIGHTS ARE LEADING THE CHARGE

Data from the APF Canada Investment Monitor shows that from 2003 to 2017, outward FDI from Canada to the Asia Pacific flowed from the four provinces with the largest economies: Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, and Quebec.

The flow of capital from these provinces, perhaps unsurprisingly, reflects the share of Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP) that these provinces have, as well as their level of participation in Canada’s two-way international trade and investment.

ONTARIO: SHIFT TOWARD RENEWABLE ENERGY AND FINANCIAL SERVICES

Ontario, as Canada’s wealthiest and most populous province, has a well-established investment relationship with the Asia Pacific. As a manufacturing and trade hub, this province is home to the majority of the Canadian workforce in technology, finance, and other knowledge-intensive industries. Its investment flows into the Asia Pacific are more than double those of Alberta and British Columbia combined, accounting for 60 percent of all Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific.

More recently, investors from Ontario have taken an increased focus on renewable energy, particularly in Japan. Since 2011, Japan’s renewable energy boom has attracted repeated investments and site expansions by Ontario-based companies. A good example is Canadian Solar, which has increased its investment in solar plants throughout the country, totalling over C$3B between 2011 and 2017. This acceleration and staggering expansion may be attributed in part to Japan’s shift in policies toward renewable energy following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011.

While the mining sector attracted the greatest proportion of Ontario-based investment into the Asia Pacific in the five years leading up to 2008, a drastic shift toward investment in financial services occurred post-recession,[15] as investors in the province looked toward this sector to fuel their growth in Asian markets.[16] In 2016 Toronto-based Canada Pension Plan Investment Board took part in a consortium with Vancouver-based British Columbia Investment Management Corporation, Toronto-based Brookfield Infrastructure Partners, and Qatar Investment Authority to acquire Australian port and rail operator Asciano Ltd. for more than C$9B. Also in 2016, Toronto-based Brookfield Asset Management purchased office and retail space in Mumbai from India’s Hiranandani Group for over C$1.3B, which is the largest commercial property investment by Canadians in India to date.

In addition to focusing on commercial real estate, Ontario-based investors have invested in educational services across the Pacific. More specifically, there has been an emphasis on secondary and post-secondary institutes opening campuses in emerging Asian markets. For example, Toronto-based Branksome Hall, a non-denominational girl’s school, opened its first campus in Asia on Jeju Island in South Korea, and Oakville-based Sheridan College established an international learning site in Singapore dedicated to animation and computer graphic design.

BRITISH COLUMBIA: CONTINUED FOCUS ON NATURAL RESOURCES WITH TECHNOLOGY ON THE HORIZON?

British Columbia, with its location next to the Pacific Ocean and deeply embedded cultural and diasporic ties to the Asia Pacific, remains the major provincial economy with the largest share of exports heading to Asia, the highest number of “sister city” relationships in the region, and the most flights leaving the province bound for Asia Pacific airports.

Outward investment flows from British Columbia investors into the Asia Pacific over the past 15 years has not yet recovered the volume and scale of investments in natural resources that formerly characterized the province’s Asia-bound investment focus.

Investments in energy fluctuated between 2003 and 2008, but gradually increased to reach a peak in 209, where a small number of large-value investments in renewable energy accounted for almost 68 percent of investments across all industries that year. Steadily renewed interest in the mining and chemical sector has resulted in gradual investment growth over the past several years and, in addition to natural resources, British Columbia-based companies have expanded investments in industrial goods to include transportation and logistics services in the Asia Pacific region.

There has been, however, a steady number of medium-sized investments from innovative companies located in British Columbia’s technology hubs of Richmond and Vancouver. While technology investments in Beijing and Shanghai previously attracted most overseas investment, fierce competition, shifting consumer demands, and red tape in China have led many companies to invest in ASEAN economies, such as Singapore and the Philippines.

Although gold mining has been the most consistent target for British Columbian investment into Asia Pacific countries from the early 2000s to the present, fast-growing markets in the region have more recently presented British Columbia-based investors with significant opportunities in a multitude of sectors. As a result, the past five years witnessed unprecedented market diversification in investment by British Columbia-based investors into the Asia Pacific. Examples of this include two investments in cannabis products into Australia in 2017, highlighting a possible emergent industry that may experience robust growth following Australia’s approval of medical marijuana exports earlier this year (see Box 6).

Box 4. Exporting Vancouver’s Hipster Look to China

Across Canada’s many university campuses, it is hard to miss products from Vancouver-based Herschel Supply Company. Herschel, often known for its backpacks that blend simplicity and style, has quickly become the quintessential accessory for Canadian students. In 2017, Herschel chose China as the epicentre for the global Herschel phenomenon, making its Shanghai office, a wholly owned foreign enterprise, the entry point into the Chinese and greater Asia Pacific retail market.

Established in 2009 and named for the small, rural Saskatchewan town where the founders’ family immigrated from Scotland, Herschel focuses on retro-inspired bags, accessories and, more recently, clothing that banks on a sense of nostalgia and vintage authenticity. The fashion-forward company of 150 employees has since transformed the retail industry into one where backpacks are no longer solely used for students to carry their textbooks, but as a functional and stylish accessory for all. This has helped propel Herschel’s growth beyond North American borders into over 70 worldwide markets.

As one of the world’s fastest-growing bag and travel accessory companies, Herschel’s headquarters in Vancouver offers many strategic advantages, including geographic proximity to the rapidly expanding – and changing – consumer markets of the Asia Pacific. In recent years, a noticeable shift has occurred in China’s fashion retailing. As hordes of young millennials – approximately 415 million people, or 65 percent of China’s total consumer growth – head into the workforce, western fashion chains have been attempting to capitalize on these more fashion-conscious shoppers. In doing so, they have contributed to China’s upswing in retail sales that have catapulted the economy forward as the country shifts from one that is predominantly export-driven to a more consumer-oriented society.

Having already carved out a lucrative niche among trendy young shoppers in North American markets, Herschel has also capitalized on the growing trend of an “experience economy,” subscribed to by younger populations around the globe that prefer to spend their money on travel and events – and want to look fashionable while doing so.

By testing the waters in a variety of Asia Pacific economies through a network of 7,000 third-party retailers and rapidly growing e-commerce markets abroad, Herschel’s expansion of a permanent office in Shanghai signals the company’s ambitious objective of conquering China’s constantly fluctuating consumer base and making these consumers a cornerstone of its global marketing strategy.

ALBERTA: INVESTMENT FUTURE IN NEW FORMS OF ENERGY?

Alberta is the epicentre of the energy industry in Canada and, while investment has declined in tandem with the price of oil, this sector continues to be the province’s largest source of outbound investment. Within the industry, oil and gas exploration and production retained the largest share of investment into the Asia Pacific between 2003 and 2017. Although there have been signs of recovery after the economic crisis in 2008, global economic uncertainties continue to plague the province’s oil and gas sector, arising from commodity price volatility. As a result, the volume of investments has remained consistent across years, but the scale of investments is unsurprisingly low.

Despite these economic setbacks, Alberta’s investment into the Asia Pacific is slowly on the rise as the impact of the commodity shock abates. In 2014, Alberta saw its largest Asia Pacific investment in oil and gas production in almost a decade when Calgary-based Baytex Energy Corporation purchased Australia’s Aurora Oil and Gas Limited for C$2.7B. Such investment suggests a pivot away from the dependence on greenfield projects that dominated outbound investment between 2003 and 2008. Going forward, Alberta-based oil and gas companies, due to a halt in progress on the Trans Mountain pipeline, may look to retain a share of the market abroad through the acquisition of already-established companies in Asia.

While investors from Alberta are likely to continue to invest significantly in the energy sector (as countries such as China, Japan, and South Korea look to change their energy mix), the province’s investors are likely to diversify beyond the confines of oil and gas into renewable energy and clean technology. However, if the Trans Mountain pipeline or other oil or gas transport infrastructure becomes operational, this diversification of investment may not happen to the same extent, as more investment may be poured in to support a more efficient way for Alberta’s traditional energy exports to reach the Asia Pacific’s key markets.

QUEBEC: SECTOR DIVERSIFICATION HIGHLIGHTS GROWING TRANSPORTATION AND LOGISTICS INDUSTRY

Quebec has worked hard to build substantial linkages with much of the Asia Pacific. The effort has paid off and trade with this region has increased by 235 percent since 2000. APF Canada Investment Monitor data shows that much of the FDI from Quebec into the Asia Pacific over the past 15 years focused on the mining industry. However, investment outflows over the past several years demonstrate an overt shift in sector focus away from a primary reliance on aluminum production toward diversification in specialized consumer services and industrial goods.

In addition to mining, Quebec’s vibrant transportation industry has seen consistent investment outflows as the province boasts major innovative players in a number of key sectors. More specifically, there has been an emphasis on the establishment of commercial transportation manufacturing, such as railway equipment, aircraft-oriented systems, and logistics facilities. Bombardier has been one of Quebec’s largest investors, opening 20 support centres alone since 2010. Recent years have seen investment booms in this evolving industry, geographically concentrated in markets such as Malaysia, Singapore, and India.

REST OF CANADA: MAXIMIZING OPPORTUNITIES IN SELECTED INDUSTRIES

Natural-resource-based industries remained the largest source of direct investment into the Asia Pacific from Canada’s smaller provinces from 2003 to 2012. More specifically, uranium and potash mining from Saskatchewan-based companies into Western Australia and China dominated investments throughout this period. However, due to significant decreases in prices and weakening demand for potash and uranium, investment from the eastern provinces shifted its focus to other industries.

Atlantic Canada has long maintained its reputation as a world leader in value-added foods, including processed, packaged, and manufactured foods. This investment relationship grew substantially in 2012 with an investment of C$74M by New Brunswick-based McCain Foods Limited to expand its existing manufacturing capacity in India.

Meanwhile, in Manitoba, Winnipeg-based Empire Industries Limited made Canada’s largest recreational-services-focused investment into the Asia Pacific through partnering with China’s Altair Space Technologies and contributing C$300M to finance a themed amusement park in Hangzhou.

Box 5. Bringing Manitoba Health Services to Asia’s Aging Population

The award-winning Manitoba-based Wellness Institute at Seven Oaks General Hospital (SOGH) remains the only facility of its kind in Canada. Its claim to fame is that it is run by a community hospital.

Built in 1996, SOGH is located in Manitoba’s capital city of Winnipeg and boasts more than 7,000 members. Throughout over two decades of operation, it has demonstrated success in addressing health issues related to an aging population and prevention of chronic disease such as diabetes, heart disease, and other conditions that are lifestyle related. SOGH takes an integrated lifestyle-medicine model to reduce governmental financial strain by extending the continuum of care and, ultimately, preventing hospitalization.

In 2011, the China Hospital Association began visits to institutes across the United States and Canada, looking to find a health-care model that could be emulated in China. According to the United Nations, China is aging more rapidly than almost any country in recent history. With a rising population of seniors, traditional diseases are on the decline and 75 percent of all deaths are currently related to chronic “lifestyle” diseases.

Ultimately, the Wellness Institute was chosen for its original and well-developed method to tackle preventable diseases, attracting the attention of Chinese medical professionals who invited representatives of SOGH to speak at several Chinese regional hospital conferences in 2013.

Speaking at the initial announcement of the partnership, Carrie Solmundson, president and chief operating officer of SOGH, said:

"The Chinese have a growing middle class and, with it, many of the same chronic diseases – diabetes, heart and lung and kidney disease – that we face in Canada. Hospitals are the mainstay of their health-care system, but they know they need to move care into the community and prevent minor conditions from becoming chronic problems."

The deal, in the form of a joint venture, is the first time a Canadian hospital has engaged in this type of international partnership, and may indicate an opening in the market for other types of Canadian public health facilities to invest in the health-care sector in aging Asia Pacific countries such as Japan and South Korea as they look for innovative ways to initiate major health-care reforms in coming years.

The challenge for Canada’s other Prairie provinces, Atlantic provinces, and territories will be leveraging momentum from the small volume of successful outward investments into the Asia Pacific, and deciding which areas to prioritize that can match provincial strengths with the needs of Asia Pacific economies.

[14] Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. Investment Monitor 2017: Report on Foreign Direct Investment from Asia Pacific into Canada.

[15] Ontario Ministry of Finance. The Changing Shape of Ontario’s economy.

[16] Conference Board of Canada. Partners in Growth: 2017 Report Card on Canada and Toronto’s Financial Services Sector.

Canada's Key Investment Destinations

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

- Australia, China, and India are the primary destinations for FDI from Canada into the Asia Pacific.

- Canadian investment in Australia was mainly in mining and chemicals from 2003 to 2014, and also in finance from 2008 to 2012.

- Canadian investment in China has declined since 2008, with most investment value concentrated in finance.

- Canadian investment into India was on the rise from 2010 to 2017. Industries aligned with the Make in India initiative have received rising levels of investment value.

- Developed economies in other Asia Pacific economies tend to have Canadian investments in service-intensive sectors, such as education and finance.

- Emerging economies in other Asia Pacific economies tend to have one investment that is large in scale.

AUSTRALIA, CHINA AND INDIA ARE THE MAIN DESTINATIONS FOR ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENT FROM CANADA

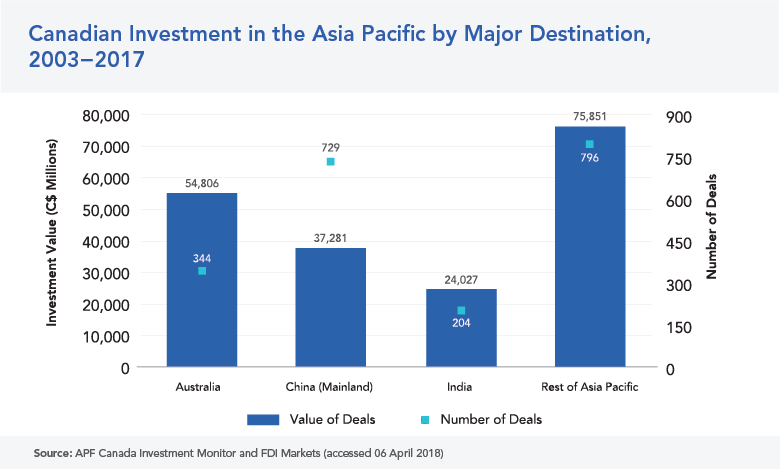

According to APF Canada Investment Monitor data, over the past 15 years, 60 percent of Canadian investment value in the Asia Pacific has occurred in three economies: Australia, China, and India. Australia is the top destination of investment, accounting for 29 percent of all investment value; China is second, accounting for 19 percent; and India is third, accounting for 13 percent.

AUSTRALIA: INVESTMENT FOLLOWING MARKET FORCES

Canada’s investment relationship with Australia is perhaps the most enduring of Canada’s investment ties in the region. With relatively similar economic profiles between the countries, Canadian and Australian multinational corporations have a strong history of investment ties between both countries’ natural-resource-based industries. This makes the two-way investment relationship susceptible to changes in global commodity prices.

Australia’s policy toward FDI is generally welcoming. Australia recognizes that foreign investment supports economic growth and innovation. Certain foreign acquisitions are reviewed on a case-by-case basis if they are deemed a potential threat to the national interest.[17]

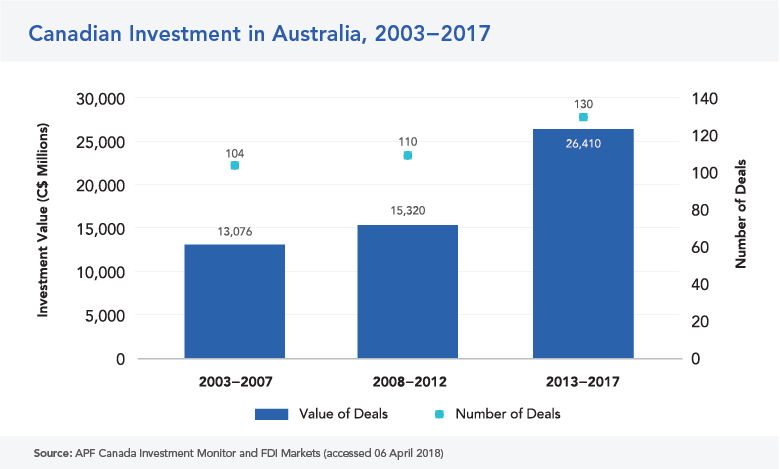

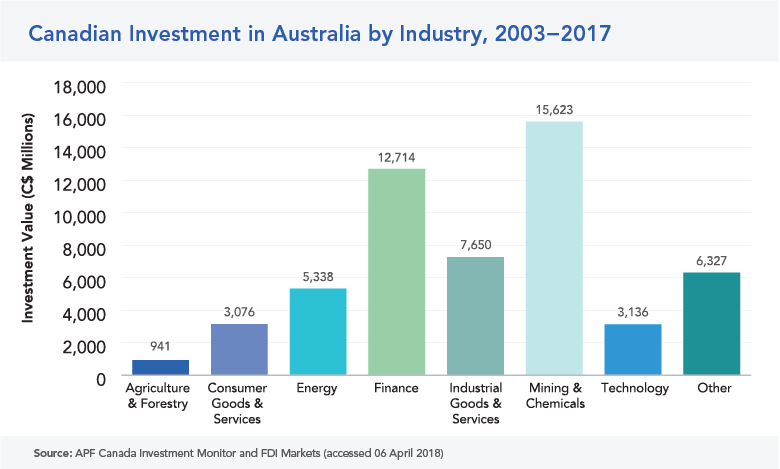

APF Canada Investment Monitor data shows that the value of FDI flow from Canada to Australia has risen over the past 15 years. While flow slightly increased from C$13.1B in 2003 to 2007 to C$15.3B in 2008 to 2012, there was a significant increase in investment value in 2013 to 2017, to almost C$26.5B. The increase in investment value in this period is primarily due to large increases of FDI in consumer goods and services, energy, industrial goods and services, and technology that more than offset a major decline in mining and chemical investment.

Canadian investment in Australia between 2003 and 2017 was mainly focused in mining and chemicals, attracting C$15.6B in investments, followed by finance with C$12.7B, and industrial goods and services with C$7.7B.

Investment flows in these three sectors were heavily concentrated in certain years, with 61 percent of the investment value in mining and chemicals occurring between 2003 and 2007, 53 percent of the investment value in finance happening from 2013 to 2017, and 87 percent of investment value in industrial goods and services transpiring in 2013 to 2017.

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reinforces these findings. The ABS states that, as of 2016, the sectors of the Australian economy that received the highest levels of investment were mining and quarrying, manufacturing, and real estate services.

The fact that these large Canadian investments in mining and chemicals coincide with significant increases in the Reserve Bank of Australia’s base metal index may suggest a link with changing commodity prices. As for finance and industrial goods and services investments, there seems to be a connection with Australia’s state and federal asset recycling scheme introduced in 2012, an initiative to auction existing state-owned assets, such as ports and roads, to raise capital for further infrastructure financing. For example, the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS) was part of the consortium that acquired the Port of Melbourne for C$9.8B in 2016.

Box 6. High Expectations

In Canada, while marijuana enthusiasts are marking their calendars for legalization of pot across the country, Canadian entrepreneurs are seeking out new opportunities for investment in the Asia Pacific. Vancouver-based companies Aurora Cannabis and PUF Ventures are both taking investment diversification in Australia to a new high.

In Australia, medical marijuana emerged as an important area of investment following its legalization in the country in 2016. With Canada being one of the handful of countries in the world that allows medical marijuana exports, Canadian firms are well-placed to serve increased demand in the Australian market and establish domestic production facilities in market. An estimated three million Australians suffer from chronic pain – the target market for medical marijuana.

In terms of the investments, Aurora Cannabis acquired a 20 percent stake in Australia’s Cann Group in March 2017 for C$6.6M, and PUF Ventures, as part of a joint venture called the Northern Rivers Project, invested C$50M to build a one-million-square-foot facility in Casino, New South Wales, to cultivate, produce, and manufacture medical marijuana. The facility will have the capacity to produce 100 tonnes of cannabis per year and is worth between $800M and $1.1B.

The local government in Casino, the Richmond Valley Council, is giving a 27-hectare site to the Northern Rivers Project for five years at no cost. The council cited the local economic and employment opportunities for wanting to develop the industry. According to PUF Ventures, if Australia were to take the same route as Canada and legalize non-medical marijuana, the marijuana market in Australia could grow to $9B in the next seven years. This could pose a significant return on investment for both Aurora Cannabis and PUF Ventures.

In addition, with Australia also legalizing the export of medical marijuana in January 2018, Canadian customers may start seeing some Canadian-owned cannabis from Australia on the shelves at home.

CHINA: CANADIAN INVESTMENT FOCUSED ON FINANCE

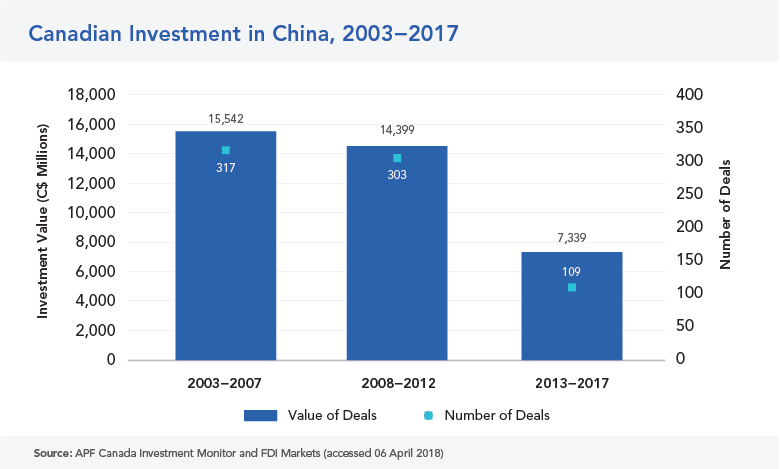

Mainland China’s ability to attract global investment has increased dramatically over the past 15 years. According to official statistics, in 2016 the world’s second-largest economy was the third-largest destination for global inward FDI.[18] Although APF Canada Investment Monitor data shows that in recent years investment flows from Canada to China have declined, the finance sector has attracted the highest value of investment.

In recent years, China’s policies regarding inward FDI have relaxed. In 2017, the State Council of China laid out new measures to further open up the economy. First, China is reclassifying various sectors of its economy to make them more open to foreign investment, particularly seeking investment in the service and advanced manufacturing sectors to assist an economic transformation toward greater domestic consumption. Second, China indicated that it will enhance the openness and transparency of its investment regulations environment. And third, China will give more autonomy to local governments in the formation of foreign investment policy.[19]

The flow of Canadian investment was initially quite high from 2003 to 2007 and 2008 to 2012, at C$15.5B and C$14.5B, respectively; however, investment value fell by almost half of these previous periods to C$7.3B between 2013 and 2017.

The decline was also exhibited across various industries, suggesting that larger macro-economic forces were at play. The decline in investment could be due to the maturation of the Chinese economy in recent years, as China has shifted from export-oriented industrialization to consumption-driven growth, and GDP growth, albeit still high, has slowed. Rising labour costs, increased competition in labour-intensive industries, and concern over state overreach may have also contributed to this decline.[20,21]

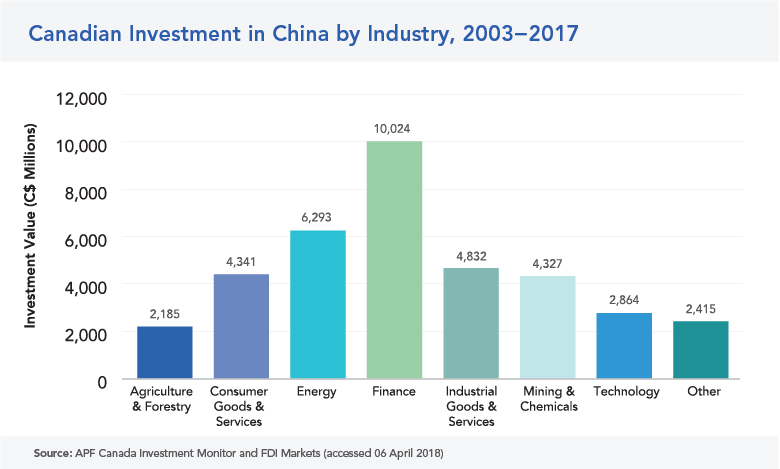

Over the past 15 years, Canadian investment in China has primarily focused on finance with C$10B of investments, followed by energy with C$6.3B, and then industrial goods and services with C$5.1B.

Within finance, about 39 percent of investment was in real estate holding and development and real estate services. The Canada Pension Plan Investment Board and Ivanhoé Cambridge were significant investors, and the vast majority of investment in real estate was in shopping malls and offices, reflective of the broader shift in China’s economy toward domestic consumption and services. Collectively, they invested C$2.3B in shopping malls and offices.

According to Invest in China, an agency within China’s Ministry of Commerce, the sectors attracting the most FDI from all sources as of 2016 were manufacturing, real estate, and leasing and business services, showing some overlap with Canadian investment in the country.[22]

INDIA: PUNCTUATED BY LARGE INVESTMENTS

The economic rise of India has led to increased investment pouring into the world’s largest democracy in the past 15 years. According to official statistics, India was the ninth-largest destination for FDI inflows in the world in 2016.[23]

Since 1991, India has strived to simplify and open up its foreign investment environment. In recent years, India has launched a series of initiatives to attract foreign investment, such as the Make in India and Invest India initiatives. Make in India is a program to turn India into a global manufacturing centre by attracting and facilitating investment and business in the country through reducing FDI restrictions on 25 sectors.[24] Invest India is a first point of reference for international firms seeking to invest in India.

The perception for most international companies, however, is that India’s foreign investment policies often remain difficult to understand, with some sectors varying in the amount of market share that can be held by foreign entities and others requiring government approval or requiring investment be conducted through a joint venture with a domestic Indian firm.[25]

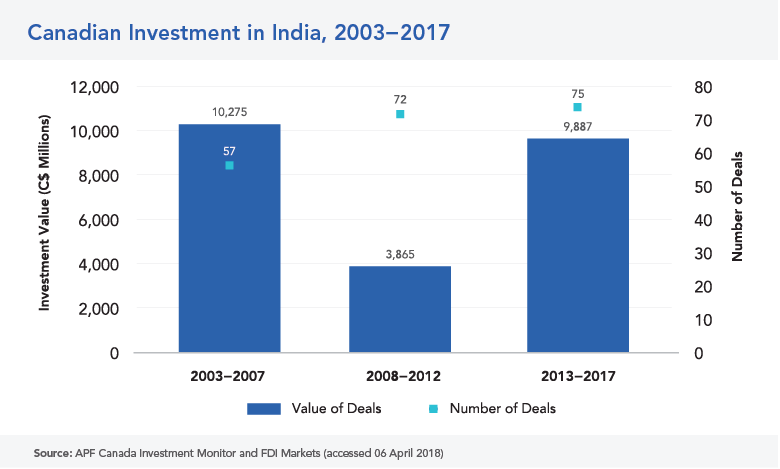

Canadian investment into India was substantially higher in 2003 to 2007 and 2013 to 2017 than in 2008 to 2012. The higher flows in these periods was because of two substantial investments totalling C$7.8B in 2004, accounting for 99 percent of total investment value in that year, and two large investments of C$3.5B in 2016, accounting for 69 percent of all 2016 investment value.

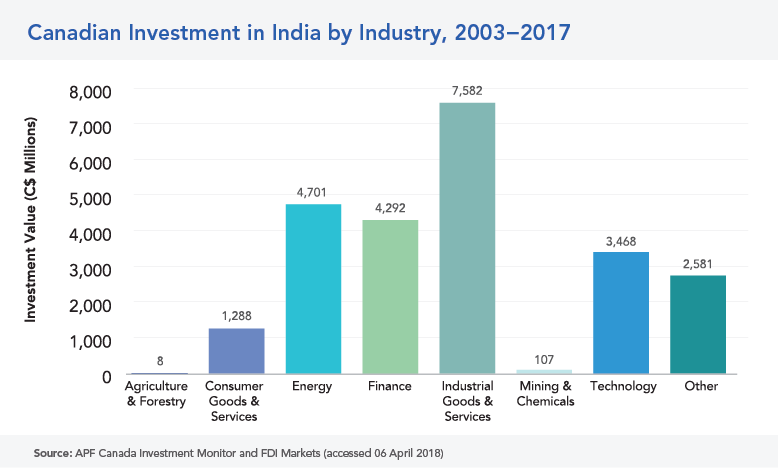

Industrial goods and services, energy, and technology were the industries with the most Canadian investment in terms of value. To a degree, Canadian investment into India aligns with general investment trends reported by India’s Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, where between 2000 and 2016 investment was concentrated in the services sector, telecommunications, and computer software and hardware.[27]

Canadian FDI in India is often connected to newly announced market opportunities. For example, Magna International’s investment in transportation, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board’s investment in logistics, and Magellan Aerospace’s investment in aerospace original equipment manufacturers all align with the Make in India initiative. Canada’s largest energy investment in India, C$3B in 2004 by Calgary-based Niko Resources Ltd. in the Bay of Bengal, came after a discovery of deep-water gas in the body of water off India’s coast.

OTHER ASIA PACIFIC ECONOMIES: EXTENSIVE DISTRIBUTION AND A FEW BIG INVESTMENTS

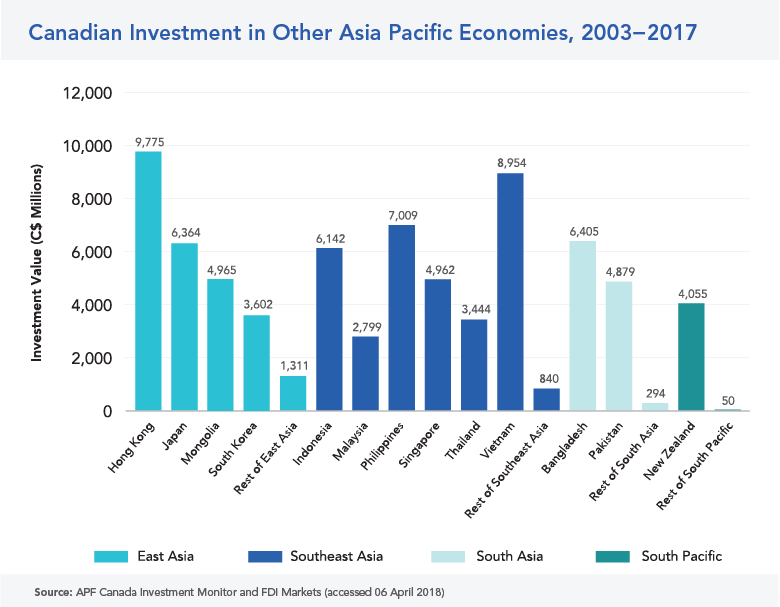

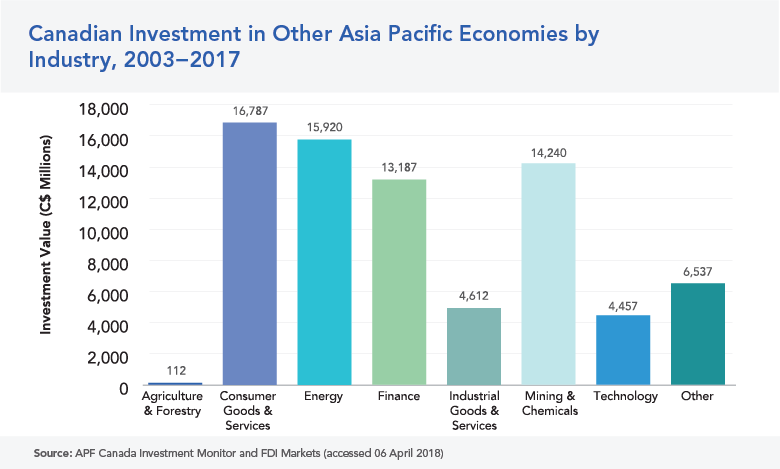

Although Canadian investment into the other Asia Pacific economies varies, over the past 15 years, investment tends to have shifted from developed to developing economies. Canadian investment in other Asia Pacific economies from 2003 to 2017 totaled C$76B, or 40 per cent of total Canadian FDI in the Asia Pacific during this period. Southeast Asian economies account for 45 percent of this investment, other economies in East Asia account for 34 percent, other South Asian economies account for 15 percent, and other South Pacific economies account for 5 percent.

Among these economies, Canadian investment in consumer goods and services, energy, and mining and chemicals were the most popular industries for investment.

Canadian FDI in the Asia Pacific’s other developed economies was in service-intensive sectors such as education and finance. In Hong Kong, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board was part of a joint venture to purchase Nord Anglia Education Inc. for US$4.3B. In Japan, a subsidiary of Brookfield Asset Management purchased Industrial Developments International Inc. from Kajima Corp. for C$1.1B.

Investment value in developing economies is often concentrated in a few investment deals. This trend is most acute in Bangladesh, where a renewable energy investment in 2015 worth almost C$6B accounts for 92 percent of Canadian investment into Bangladesh from 2003 to 2017. Another example is from Vietnam, where a C$5B hotel development in 2008 accounted for 54 percent of Canadian investment value into Vietnam over the past 15 years. These initial large investments in developing economies show that Canadian firms are willing to invest in an opportunity and could set a precedent for more sustained investment in these markets from other Canadian firms in the future.

[17] Australian Trade and Investment Commission.

[18] UNCTAD. World investment report 2017.

[19] Jin. China’s New Policies on Foreign Investment. Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, March 2017.

[20] Wang. Navigating FDI in China as the Economy Slows. Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, May 2017.

[21] Deutsche Welle. Foreign direct Investments into China Slowing Down.

[22] Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China. Statistics on FDI in China 2017.

[23] UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2017.

[24] Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (India). Make in India.

[25] National Investment Promotion and Facilitation Agency of India.

[26] Includes finance, banking, insurance, non-financial and business services, outsourcing, research and development, couriers, and technology testing analysis.

[27] Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (India).

Conclusion

The Asia Pacific is emerging as the central hub of global economic activity, with many economies presenting unique opportunities for foreign investment. Canadian Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the Asia Pacific is helping foster wider economic engagement with the region, but beyond the limited information available from official statistics, Canadians understand very little about the impact of Canada’s two-way investment relationship with the Asia Pacific. The lack of detailed knowledge about the volume, scale, scope, and impact of Asia Pacific investment in Canada can lead to inadequate policies and a misinformed public.

The APF Canada Investment Monitor lays the groundwork for evidence-based decision-making by providing the public with a growing data set of investment deals by Asia Pacific-based companies in Canada, and Canadian-based companies in the Asia Pacific. By providing this information as a free and open resource, APF Canada hopes to provide a core set of facts about the number, size, and distribution of investment deals between Canada and the Asia Pacific that governments, businesses, researchers, and the public can use to better understand Canada’s investment relationship with the region.

Methodology

The APF Canada Investment Monitor tracks foreign direct investment announcements at the firm level, taking a bottom-up approach rather than reviewing the balance of payments in Canada’s national accounts.

In order to generate the APF Canada Investment Monitor data, APF Canada uses its own unique legacy data, third-party data sources, metasearch engines, and other search tools to aggregate data obtained from public sources including media reports, company documents, industry associations, investment promotion agencies. Investment announcements that will be entered in the database include greenfield investments, asset purchases, equity investment, mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures, etc.

The APF Canada Investment Monitor sources its investment stories primarily from its decades-long archive of announcements on deals, trade missions, MoUs and other developments of note in the Canada-Asia relationship. Such a vast archive allows the APF Canada Investment Monitor to build a strong foundation on which to track deal flow both historically and going forward. Each deal announcement is recorded, catalogued, and added to our database. Deals are recorded using 26 different observations ranging from parent company to destination city. Key to this cataloguing of investments for trend analysis is the use of a user-friendly sector classification system. Whereas deals catalogued with the widely used North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) often hide key trends in budding industries, the APF Canada Investment Monitor’s use of the modified Industrial Classification Benchmark (Modified ICB) allows it to clearly see growth in areas such as clean tech and the video gaming industry.

Dollar values for the APF Canada Investment Monitor are obtained through a thorough investigation of the deal value and, barring an official value, the best publicly available estimate. This methodology allows for the avoidance of errors that occur in databases that estimate deal value using proprietary algorithms.

Data for this report was also obtained from the United Nations Committee on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Statistics Canada (StatCan), and Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China (MOFCOM), Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), and Statistics Singapore.

Appendix

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ABS | Australian Bureau of Statistics |

| APF Canada | Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada |

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| CPTPP | Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership |

| FDI | Foreign direct investment |

| FIPA | Foreign investment promotion and protection agreement |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| ICB | Industrial Classification Benchmark |

| JETRO | Japan External Trade Organization |

| M&A | Mergers and aquisitions |

| MOFCOM | Ministry of Commerce (People's Republic of China) |

| MOU | Memorandum of understanding |

| NAICS | North American Industrial Classification System |

| SOE | State-owned enterprise |

| StatCan | Statistics Canada |

| UNCTAD | United Nations Conference on Trade and Development |

BOXES

Box 1. Cross-Border Investment and FDI

Box 2. Canadian Pension Funds Leading the Way

Box 3. Types of Cross-Border Investments

Box 4. Exporting Vancouver's Hipster Look to China

Box 5. Bringing Manitoba Health Services to Asia's Aging Population

Box 6. High Expectations

FIGURES

FIGURE 1. Official Statistics on Canadian FDI Stock Abroad, 2003-2016

FIGURE 2. Canada’s Market Share of Selected Asia Pacific Economies’ Inward FDI, 2011-2016

FIGURE 3. Canadian Investment in the Asia Pacific, 2003-2017

FIGURE 4. Canadian Investment in the Asia Pacific’s Natural-Resource-Based Industries, 2003-2017

FIGURE 5. Canadian Investment in the Asia Pacific’s Non-Natural-Resource-Based Industries, 2003-2017

FIGURE 6. Canadian SOE Investment in the Asia Pacific, 2003-2017

FIGURE 7. Canadian Greenfield and Merger and Acquisition Investment in the Asia Pacific, 2003-2017

FIGURE 8. Overview of Canadian Investment by Province, 2003-2017

FIGURE 9. Canadian Investment by Province, 2003-2017

FIGURE 10. Ontario Investment in the Asia Pacific by Industry, 2003-2017

FIGURE 11. British Columbia Investment in the Asia Pacific by Industry, 2003-2017

FIGURE 12. Alberta Investment in the Asia Pacific, 2003-2017

FIGURE 13. Quebec Investment in the Asia Pacific, 2003-2017

FIGURE 14. All Other Provinces’ Investment in the Asia Pacific by Industry, 2003-2017

FIGURE 15. Canadian Investment in the Asia Pacific by Major Destination, 2003-2017

FIGURE 16. Canadian Investment in Australia, 2003-2017

FIGURE 17. Canadian Investment in Australia by Industry, 2003-2017

FIGURE 18. Canadian Investment in China, 2003-2017

FIGURE 19. Canadian Investment in China by Industry, 2003-2017

FIGURE 20. Canadian Investment in India, 2003-2017

FIGURE 21. Canadian Investment in India by Industry, 2003-2017

FIGURE 22. Canadian Investment in Other Asia Pacific Economies, 2003-2017

FIGURE 23. Canadian Investment in Other Asia Pacific Economies by Industry, 2003-2017

TABLES

TABLE 1. Investment-Related Indexes

PARTNER & SPONSORS

The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) would like to acknowledge and thank our generous sponsors and partner; without their support, this project would not have been possible. This project is completed in partnership with The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary and with sponsorship from the Government of British Columbia, AdvantageBC, Bank of Canada, and Export Development Canada.

ADVISORY COUNCIL

In addition to our sponsors and partner, we would like to especially thank the sponsors’ representatives who sit on the APF Canada Investment Monitor Advisory Council and whose input and guidance from the conception to the launch of this project has proved invaluable.

Dr. Eugene Beaulieu, Professor of Economics and Program Director, International Economics, The School of Public Policy, University of Calgary.

Kelly Best, Strategic Implementation Lead, Ministry of Jobs, Trade, and Technology, Government of British Columbia.

Dr. Eva Busza, Vice-President, Research and Programs, Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada.

Kursti Calder, Director, International Strategy and Business Intelligence, Ministry of Jobs, Trade, and Technology, Government of British Columbia.

Colin Hansen, President and CEO, AdvantageBC.

Lori Rennison, Senior Policy Advisor, Canadian Economic Analysis Department, Bank of Canada.

Dr. Stephen Tapp, Deputy Chief Economist and Director, Research Department, Export Development Canada.

Claudia Verno, Director, Corporate Research Department and Senior Economist, Export Development Canada.

Sources

Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2015. 2015 National Opinion Poll: Canadian Views on Asian Investment. http://www.asiapacific.ca/surveys/national-opinion-polls/2015-national-opinion-poll-canadian-views-asian-investment

Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2017. Investment Monitor 2017: Report on Foreign Direct Investment from Asia Pacific into Canada. http://investmentmonitor.ca/insights-reports/investment-monitor-2017-report-foreign-direct-investment-asia-pacific-canada

Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2017. Iris Jin. China’s New Policies on Foreign Investment. https://www.asiapacific.ca/blog/chinas-new-policies-foreign-investment

Australian Trade and Investment Commission. Accessed March 2017. https://www.austrade.gov.au/

Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. 2017. Wynne Wang. Navigating FDI in China as the Economy Slows. http://knowledge.ckgsb.edu.cn/2017/05/16/finance-and-investment/navigating-fdi-in-china/

Conference Board of Canada. 2017. Partners in Growth: 2017 Report Card on Canada and Toronto’s Financial Services Sector. http://www.tfsa.ca/storage/reports/PartnersinGrowth2017.pdf

Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (India). Make in India. Accessed March 2017. http://www.makeinindia.com/about

Deutsche Welle. 2015. Foreign Direct Investments into China slowing down. http://www.dw.com/en/foreign-investments-into-china-slowing-down/a-18596994

European Central Bank. 2006. Christian Daude and Marcel Fratzscher. The Pecking Order of Cross-Border Investment. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp590.pdf?c043f7ab71d7334918267936b32fc304

Korea Development Institute. 1998. Seungjin Kim. Effects of Outward Foreign Direct Investment on Home Country Performance. http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8503.pdf

Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China. 2017. Statistics on FDI in China 2017. http://img.project.fdi.gov.cn//21/1800000121/File/201710/201710130912590697961.pdf

National Bureau of Economic Research. 1994. Martin Feldstein. The Effects of Outbound Foreign Direct Investment on the Domestic Capital Stock. http://www.nber.org/papers/w4668.pdf

National Investment Promotion and Facilitation Agency of India. Accessed March 2017. http://www.investindia.gov.in/about-invest-india

Ontario Ministry of Finance. 2014. The Changing Shape of Ontario’s Economy. https://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/economy/ltr/2014/ch3.html

Statistics Canada. 2017. Marc Atkins and Morgan Roesler. 2017. Foreign Direct Investment in Canada by Ultimate Investing Country. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/13-605-x/2017001/article/54868-eng.htm

UNCTAD. 2017. World Investment Report 2017. http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2017_en.pdf

About APF Canada

The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada is dedicated to strengthening ties between Canada and Asia with a focus on expanding economic relations through trade, investment and innovation; promoting Canada’s expertise in offering solutions to Asia’s climate change, energy, food security and natural resource management challenges; building Asia skills and competencies among Canadians, including young Canadians; and, improving Canadians’ general understanding of Asia and its growing global influence.

The Foundation is well known for its annual national opinion polls of Canadian attitudes regarding relations with Asia, including Asian foreign investment in Canada and Canada’s trade with Asia. The Foundation places an emphasis on China, India, Japan and South Korea while also developing expertise in emerging markets in the region, particularly economies within ASEAN.

Visit APF Canada at http://www.asiapacific.ca.