Foreword

MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT & CEO, ASIA PACIFIC FOUNDATION OF CANADA

The extraordinary first months of this new decade serve as a stark reminder of how central the Asia Pacific has become to all aspects of our lives. Now more than ever, Canada is witness to the increasing significance of the region as the engine of the new global economy – and witness to what happens when the engine stops, however temporarily.

The need for Canada to strategically deepen and diversify its linkages with the Asia Pacific has become more pressing, as even the strong, historical trade and investment ties with our partners in the United States and Europe face stress from the confluence of disease and economic downturn. As Canada looks ahead to a period of recovery and re-engagement, policy-makers, the business community, and the public will need to return to discussions – and debate – around foreign direct investment (FDI).

In 2020, the APF Canada Investment Monitor is turning its attention to the connections between Canada’s free trade agreements with Asia Pacific economies and FDI. Canada’s trade agreements provide a rules-based system that encourages both trade and investment with partners in the region. With 2019 concluding the first year of our participation in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), this report adds to our understanding of how agreements can provide a road map for Asia Pacific engagement.

Additionally, the report expands on our city-level coverage of FDI by analyzing how Canada’s cities are hubs as both investors and recipients and describing FDI’s role in rural Canadian communities. You will also find new analysis on investment in health care, pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and clean technologies, and descriptions of bidirectional impacts on FDI in 2008-2009, filling gaps in the data and analysis that is otherwise publicly available on where investment opportunities have been – and where we can expect them to re-emerge once again.

On behalf of APF Canada, I would like to acknowledge the efforts of those involved in producing this report, especially our partner, The School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary, and our sponsors – Export Development Canada, Invest in Canada, the Government of British Columbia, Advantage BC, and the Bank of Canada. I would also like to extend my appreciation to our Advisory Council members – Sarah Albrecht, Eugene Beaulieu, Joan Elangovan, Lori Rennison, Clark Roberts, Siobian Smith, and Stephen Tapp – for the valued feedback they have provided.

And finally, I would like to thank the members of our APF Canada research team who were responsible for writing and finalizing this report: Jeffrey Reeves, Vice-President, Research; Pauline Stern, Program Manager, Business Asia; Grace Jaramillo, Interim Program Manager, Business Asia; Kai Valdez Bettcher, Research Specialist; our Post-Graduate Research Scholars and Junior Research Scholars, Isaac Lo, Phebe Ferrer, and Sainbuyan Munkhbat; and APF Canada’s communications team for editing and designing the final publication, Michael Roberts, Communications Manager, and Jamie Curtis, Graphic Designer.

Stewart Beck,

President and CEO, Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada

Executive Summary

Over the past two decades, the Asia Pacific’s dynamic, fastest-growing economies have played a central role in the global economy, boasting unprecedented opportunities for foreign investment in a number of key markets – in terms of both opportunities for Canada to receive foreign investment and opportunities for Canadian investors to invest abroad.

To describe this relationship, the APF Canada Investment Monitor aggregates raw data from the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s archive of investment deal announcements from 2003 to present (see methodology section for further details).

Each year of the project corresponds with an annual theme; this year’s theme is investment and free trade agreements, with previous years focusing on inbound investment, outbound investment, and city-level data.

This annual report presents the following:

- General trends in Canada’s foreign direct investment relationship, with specific reference to the Asia Pacific, up to 2019;

- The connections between Canada’s free trade agreements in the Asia Pacific and investment; and

- Inbound and outbound relationships at the national, provincial, and city levels.

Key Takeaways from the Report

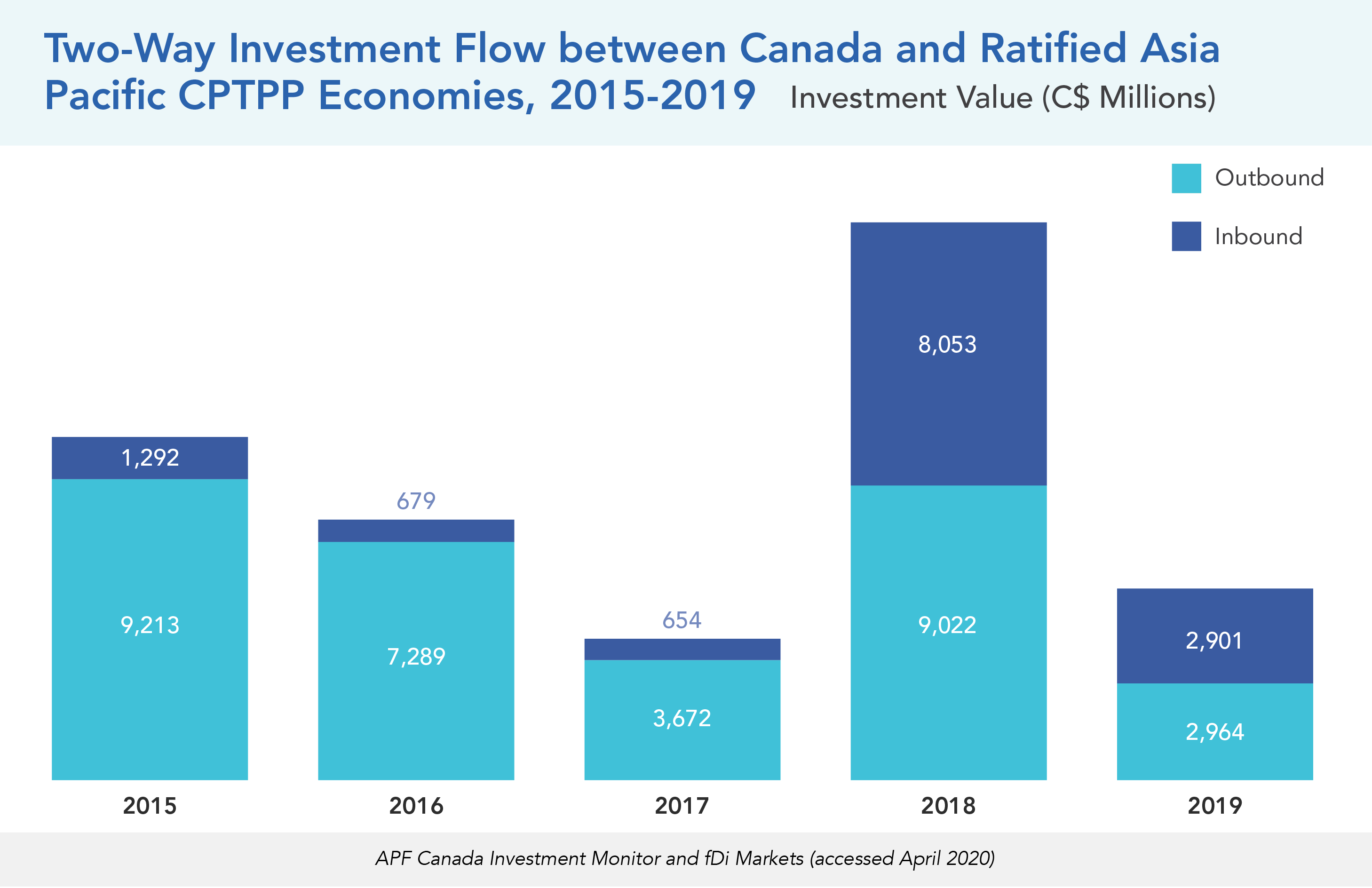

In 2019, the total two-way value of Canadian investment with CPTPP-ratified economies was C$5.8B by way of 56 deals.

Of these, C$3.0B was in Canadian outbound investment to these trade partners, while C$2.9B came into Canada. However, investment flows for 2019 between Canada and CPTPP economies decreased from 2018.

In the Asia Pacific, the strongest evidence for increased FDI after a free trade agreement is the Canada-South Korea free trade agreement signed in 2015.

Canada received an additional C$870M from South Korea from 2015 to 2019, while the total value of two-way investment flow in the period increased significantly by 35 percent, from C$5.1B in the five years prior to the agreement to C$7.8B in the five years post-agreement.

In 2019, Canada received a total of C$8.3B of foreign direct investment from Asia Pacific economies.

This represents a decline in new investment received from the historic high of C$33B in 2018. From 2015 to 2019, Canada received C$56B in Asia Pacific investment through 428 deals, hitting a 16-year high.

The number of inbound investment deals in 2019 set a record with 151 deals.

The Asia Pacific’s investment activity in Canada was high, part of a multi-year trend with investments increasing each year since 2015.

In 2019, Canada invested a total of C$7.2B in the Asia Pacific.

This represents a significant drop from 2018’s C$18B in investment. Deal counts also dropped and reached the lowest point since 2003, with only 75 outbound FDI deals made that year.

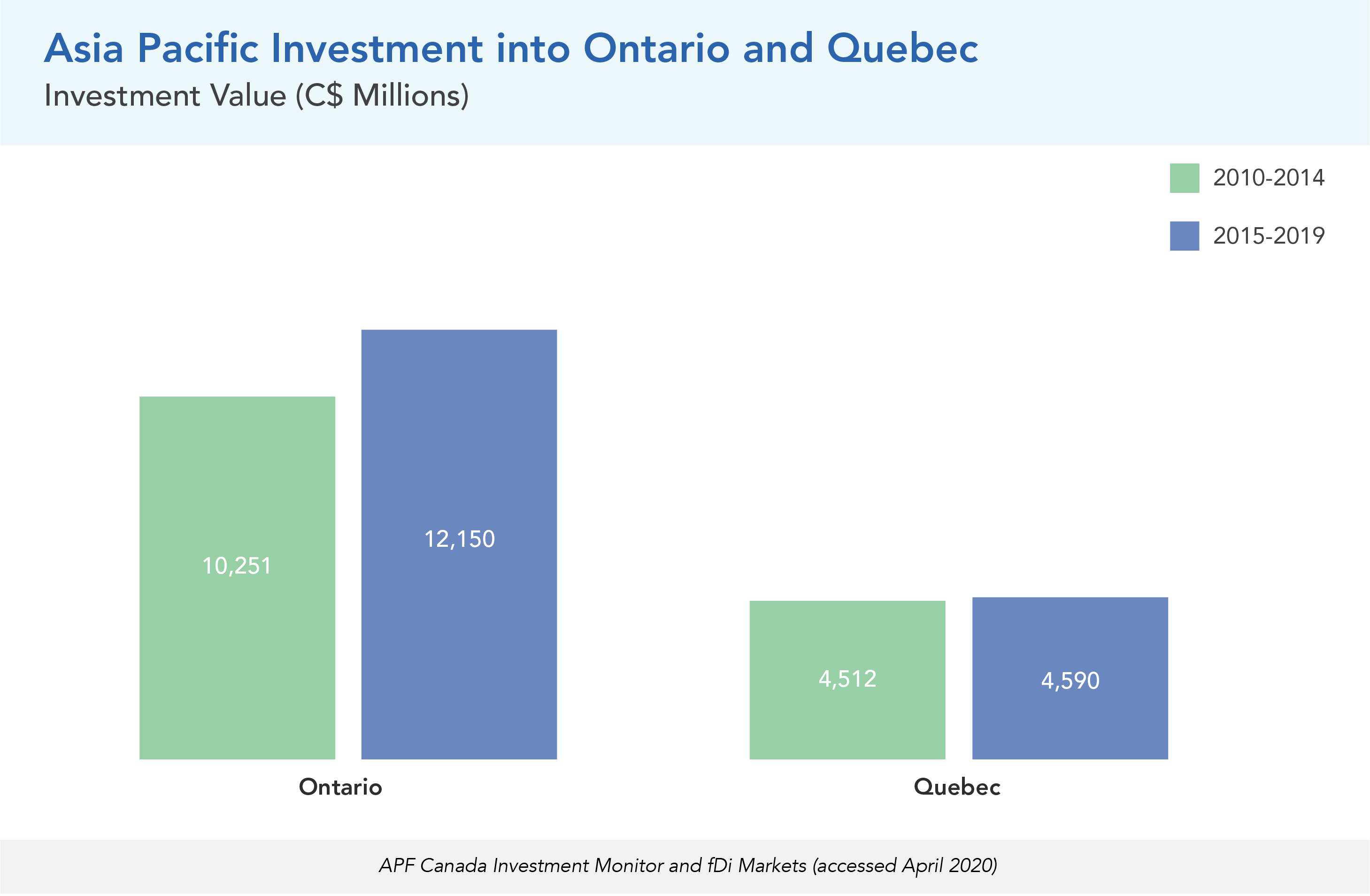

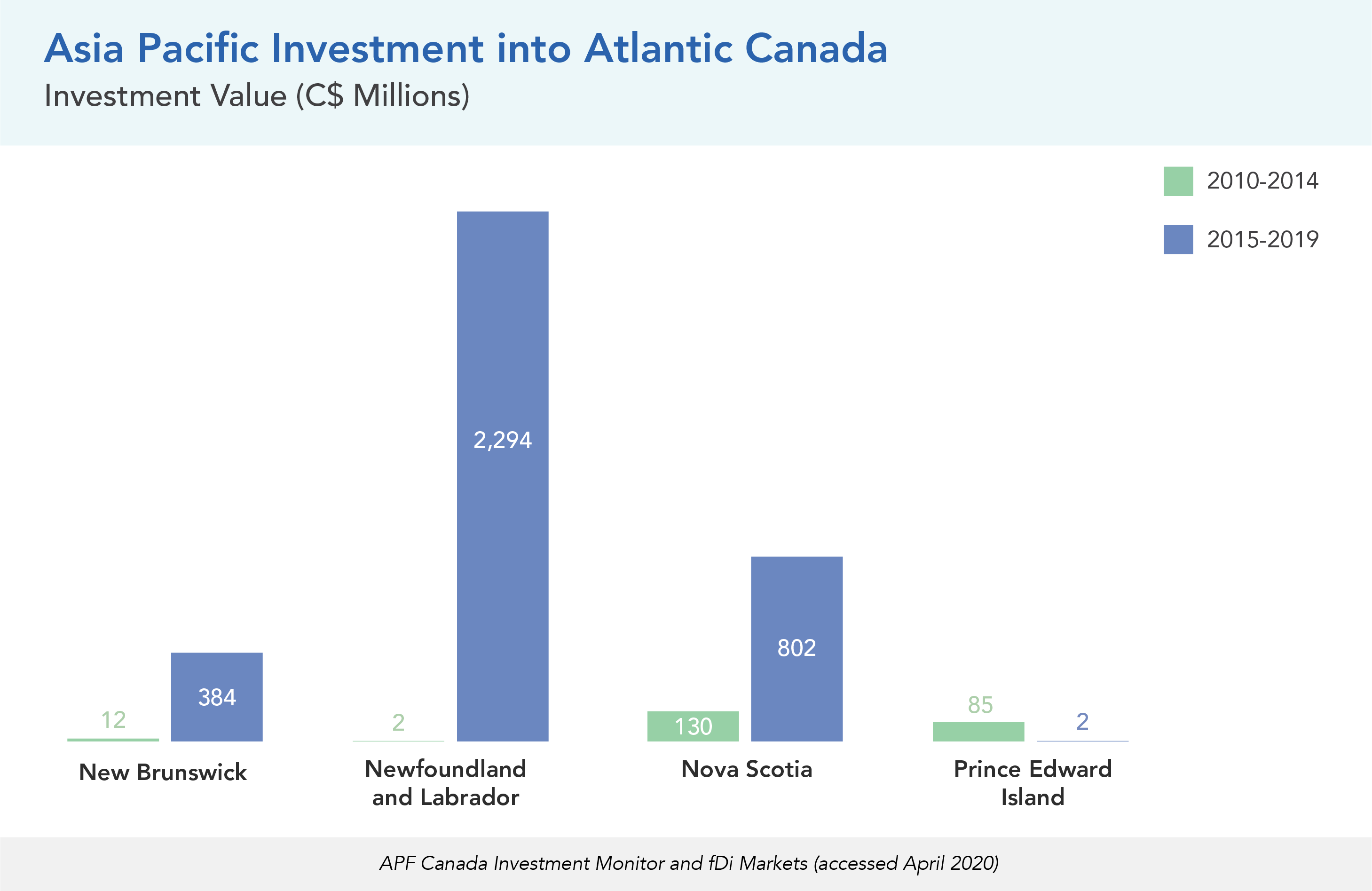

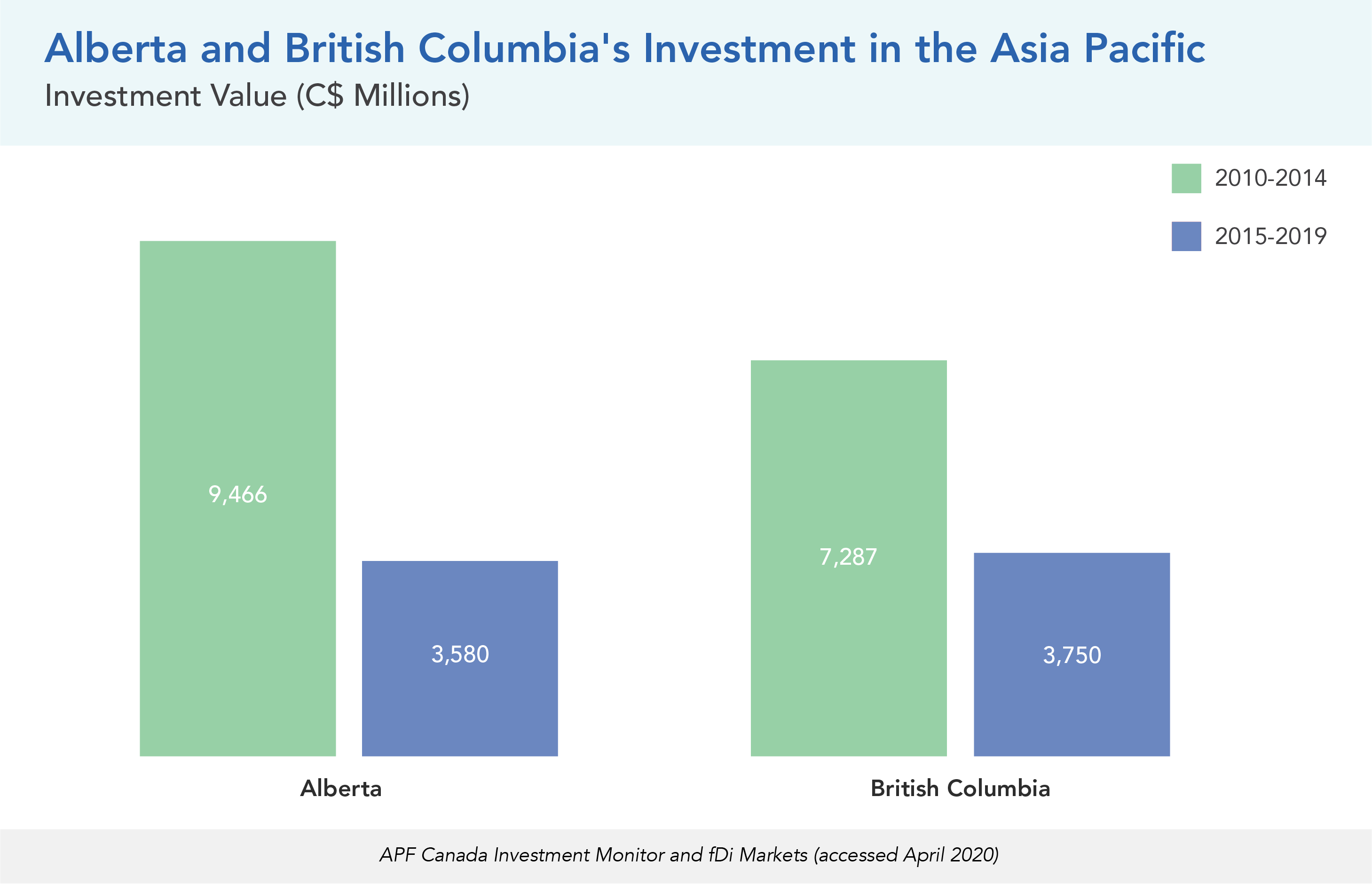

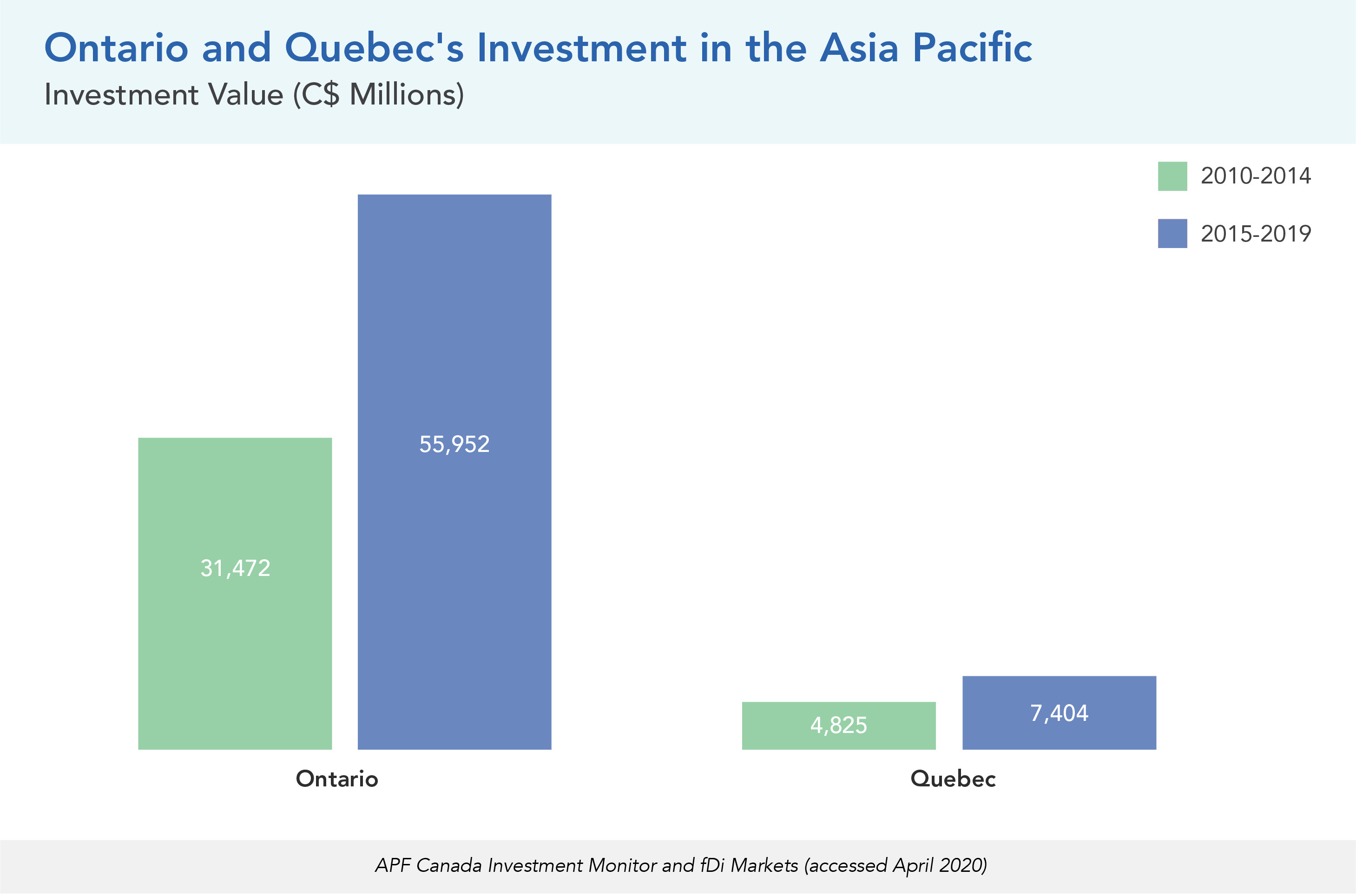

Many provinces saw increases in new investment received across the past decade.

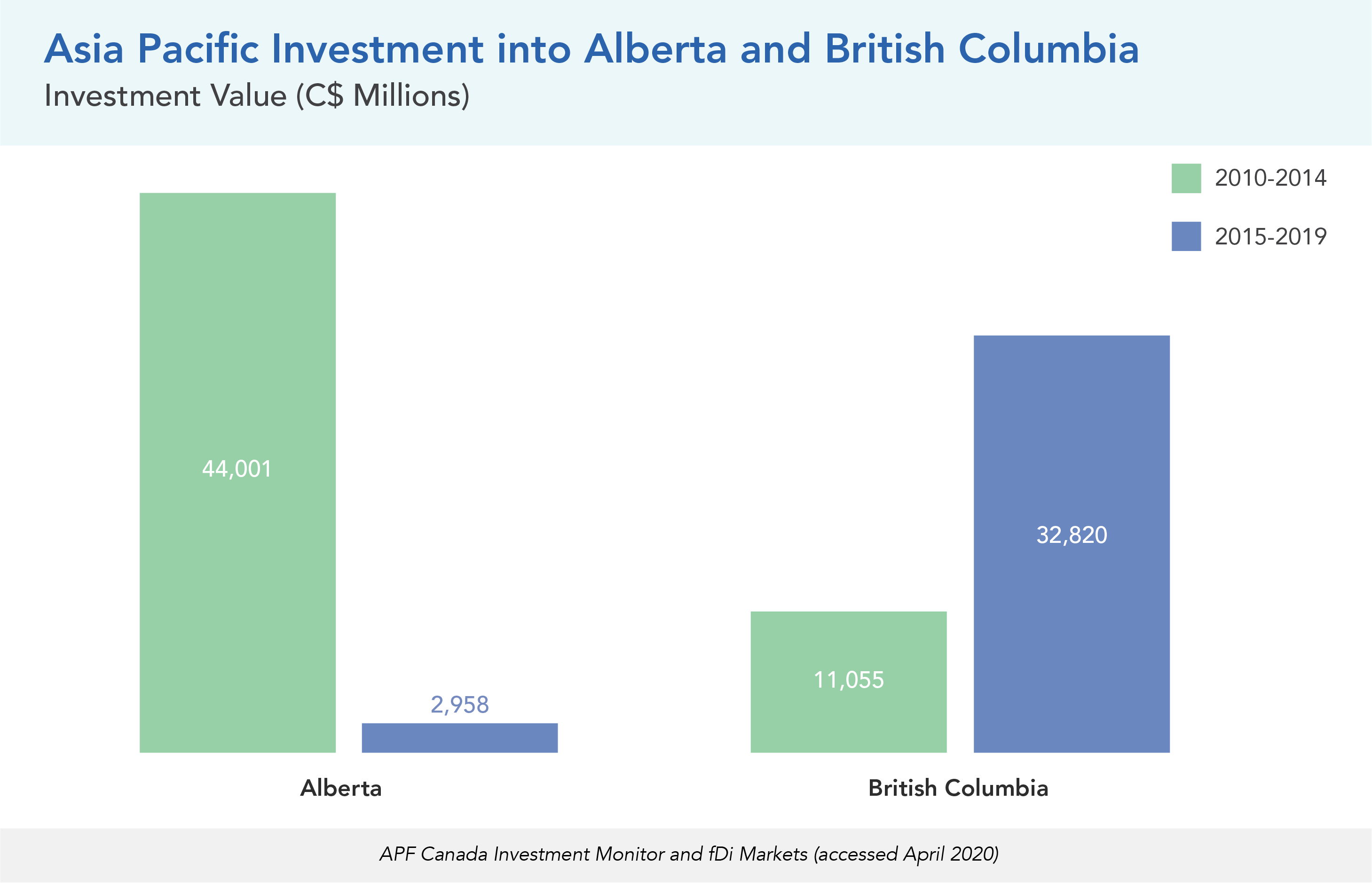

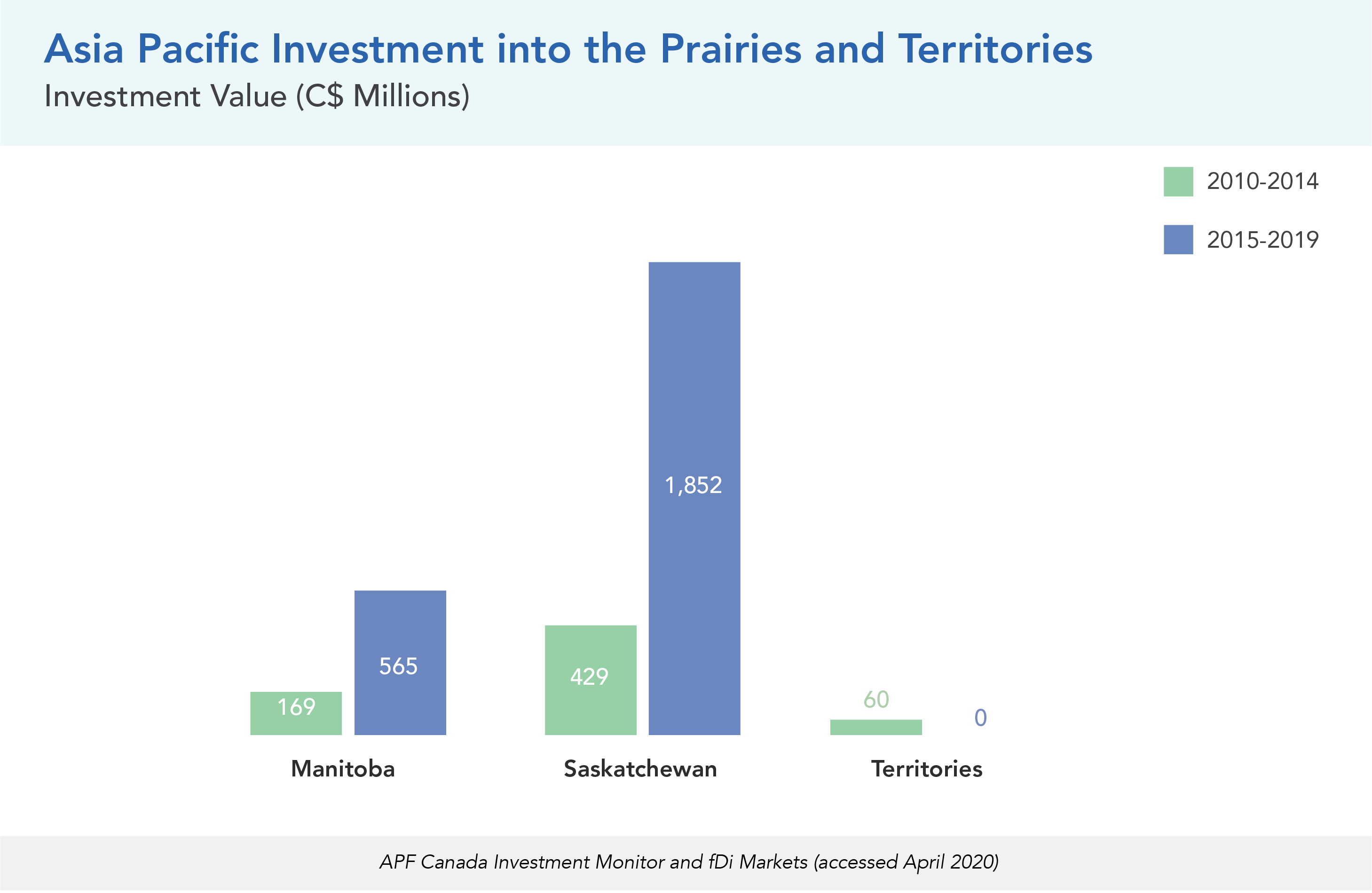

The value of Ontario’s new investments received increased C$12.6B in the second half of the decade, while Quebec added C$5.1B in new investment. Flows of Asia Pacific investment received by BC nearly tripled, rising to C$32.8B, but new Asia Pacific investment into Alberta dropped from C$44.0B in the first half of the 2010s to just C$2.9B in the second half.

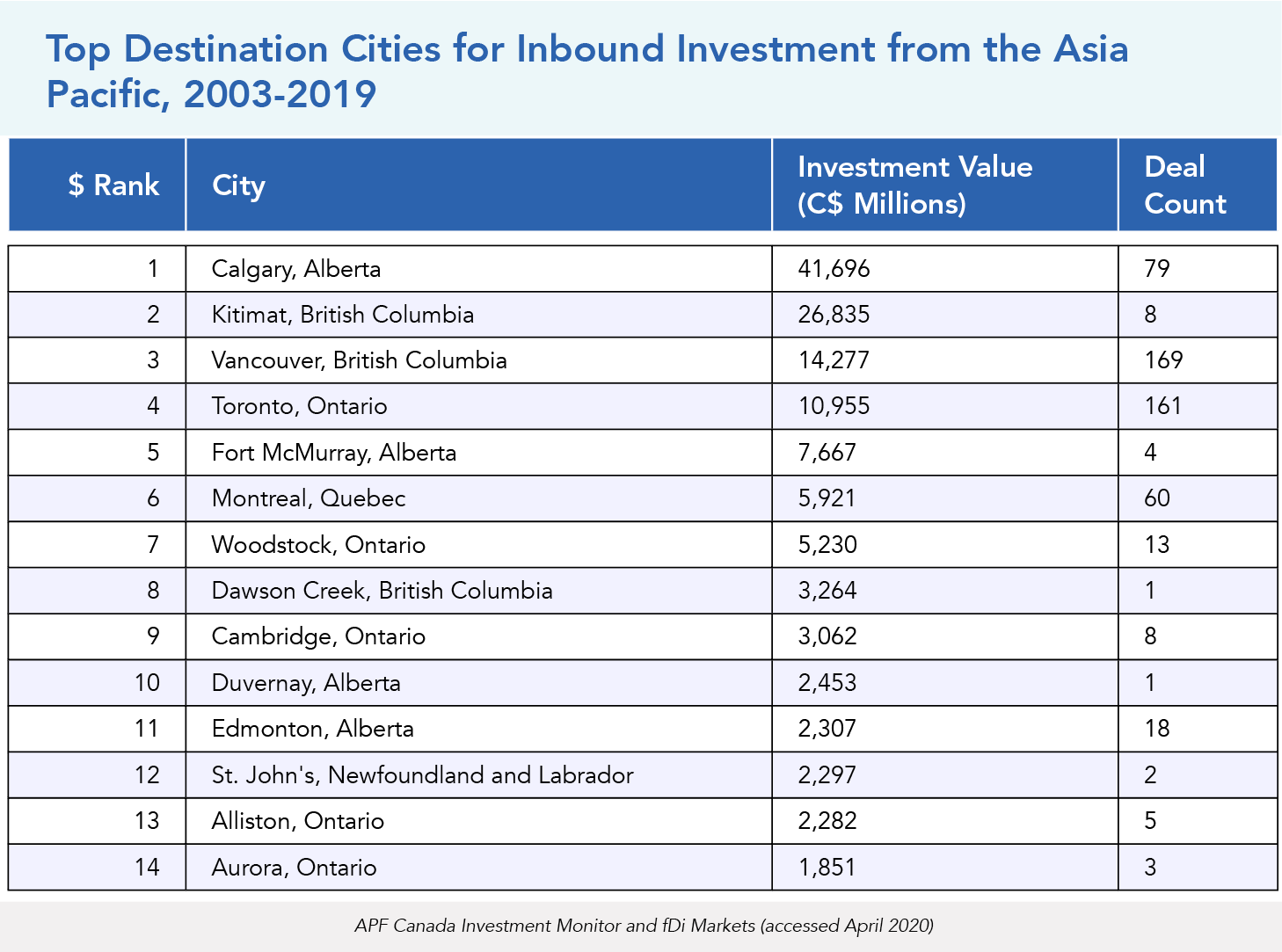

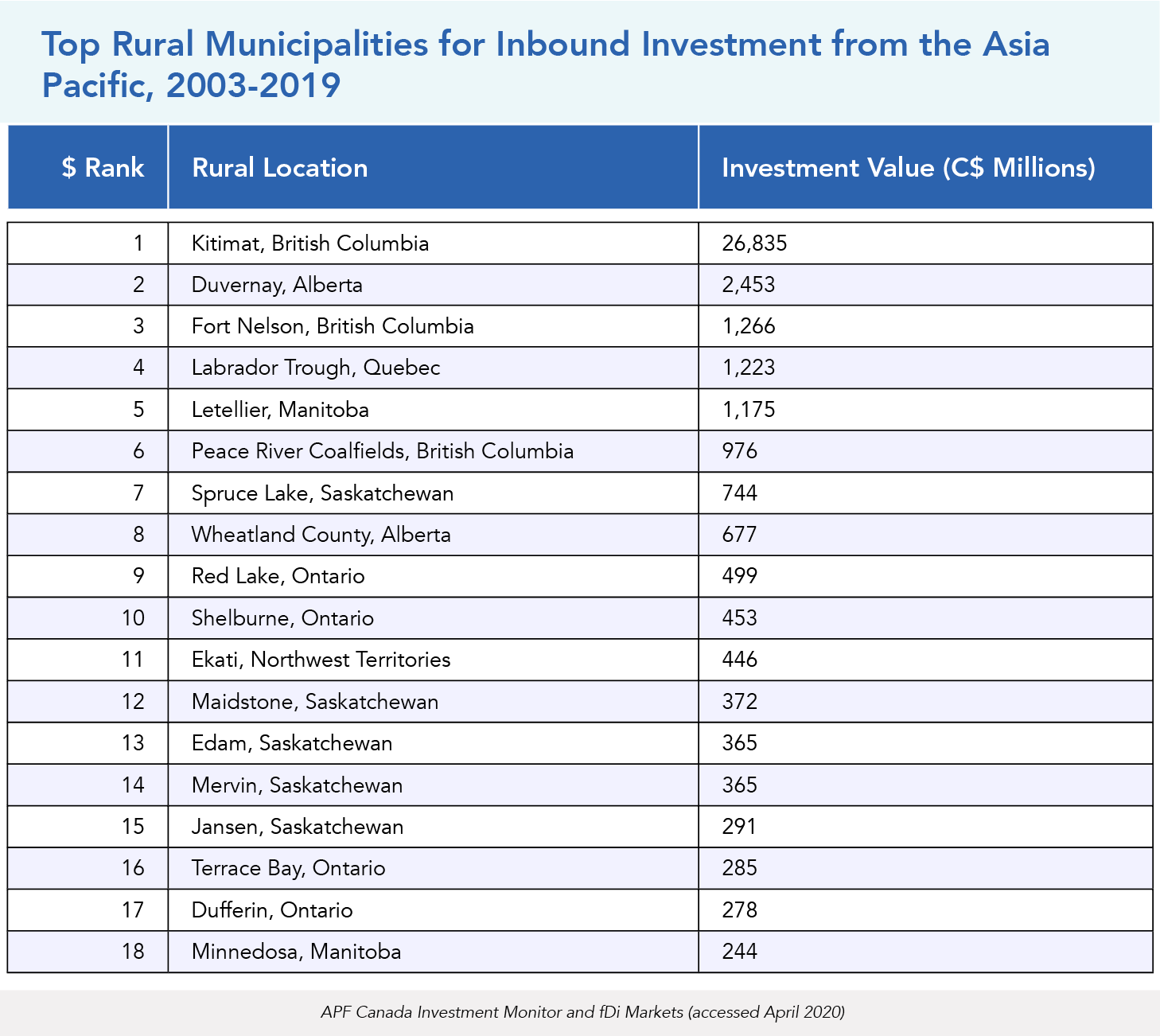

Over the past 17 years, 97 Canadian cities have invested into the Asia Pacific, and 191 cities have received investment, representing a strong network of ties across the Pacific.

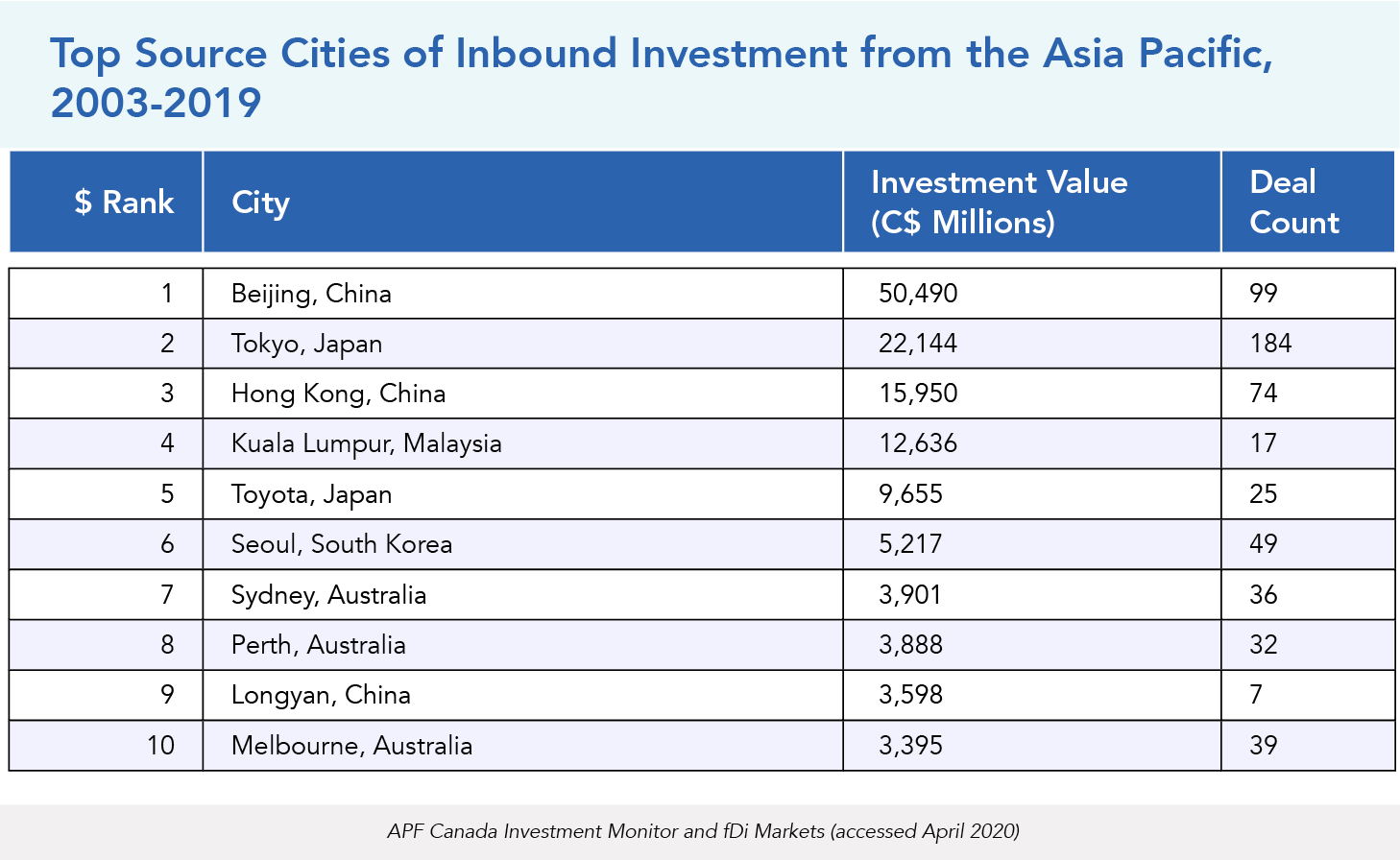

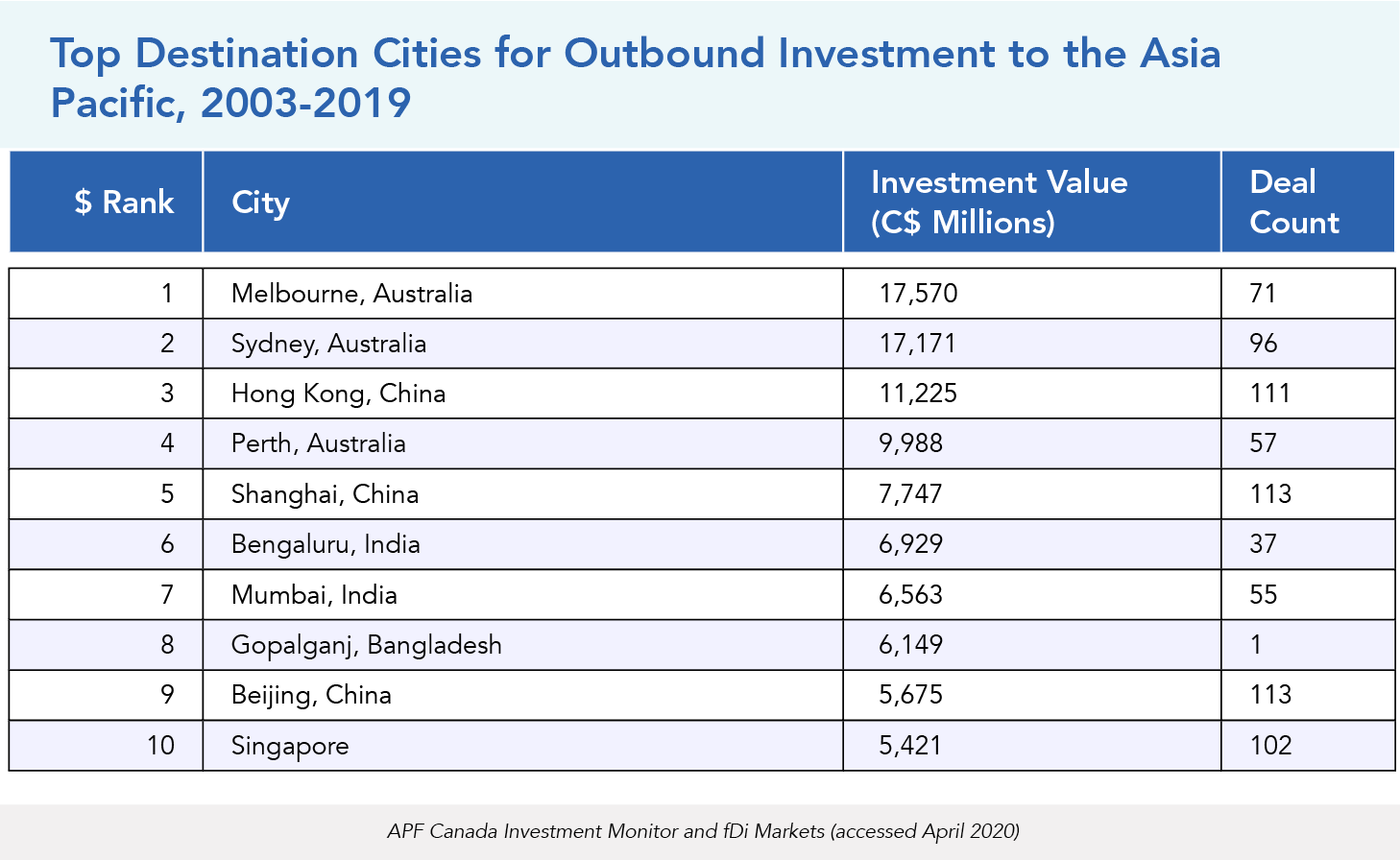

During that same period, 21 Canadian cities invested half a billion or more into the region, some with hundreds of deals. On the Asia Pacific side, Beijing, Tokyo, and Hong Kong lead as sources of investment in Canada, while Melbourne and Sydney are the top destinations for Canada.

Introduction

GENERAL TRENDS IN INVESTMENT TO 2019

With the turn of the new decade, the Asia Pacific continues to be a dynamic region of economic growth and opportunity. In 2020, some are heralding the start of an “Asian century,” where the region becomes “the new centre of the world” as it continues to grow and expand.[1] According to the 2019 World Investment Report released by the United Nations Committee on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Asia remains the largest recipient region of FDI flows, with 4 percent growth since 2018.[2] China is the second FDI receiving economy after the United States, closely followed by Hong Kong and Singapore, in third and fourth place, respectively. In particular, Southeast Asian economies like Singapore and Indonesia are expected to continue being “the region’s growth engine,” with an estimated 19 percent increase in FDI flows for 2019. Overall, in terms of shares of world GDP in purchasing power parity, the Asia Pacific region is projected to become larger than all other economies combined.

Recent developments in US-China trade tensions have led to uncertainty in the global economy, as have slowdowns in the US and Chinese economies, raising the risk of slowed economic growth.[3] Indeed, the growth of the Asia Pacific was expected to slow, even before the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic: the most recent Global Investment Trend Monitor update forecast a 6 percent drop in regional FDI inflows for 2019.[4]

For Canada, while the Asia Pacific region is a small part of its FDI flows, it is a growing region of interest. From 2015 to 2018, Canada’s FDI flows to the region made up 7 percent of its total outbound FDI. In the same period, incoming flows from the region made up 10 percent of Canada’s total inbound FDI.

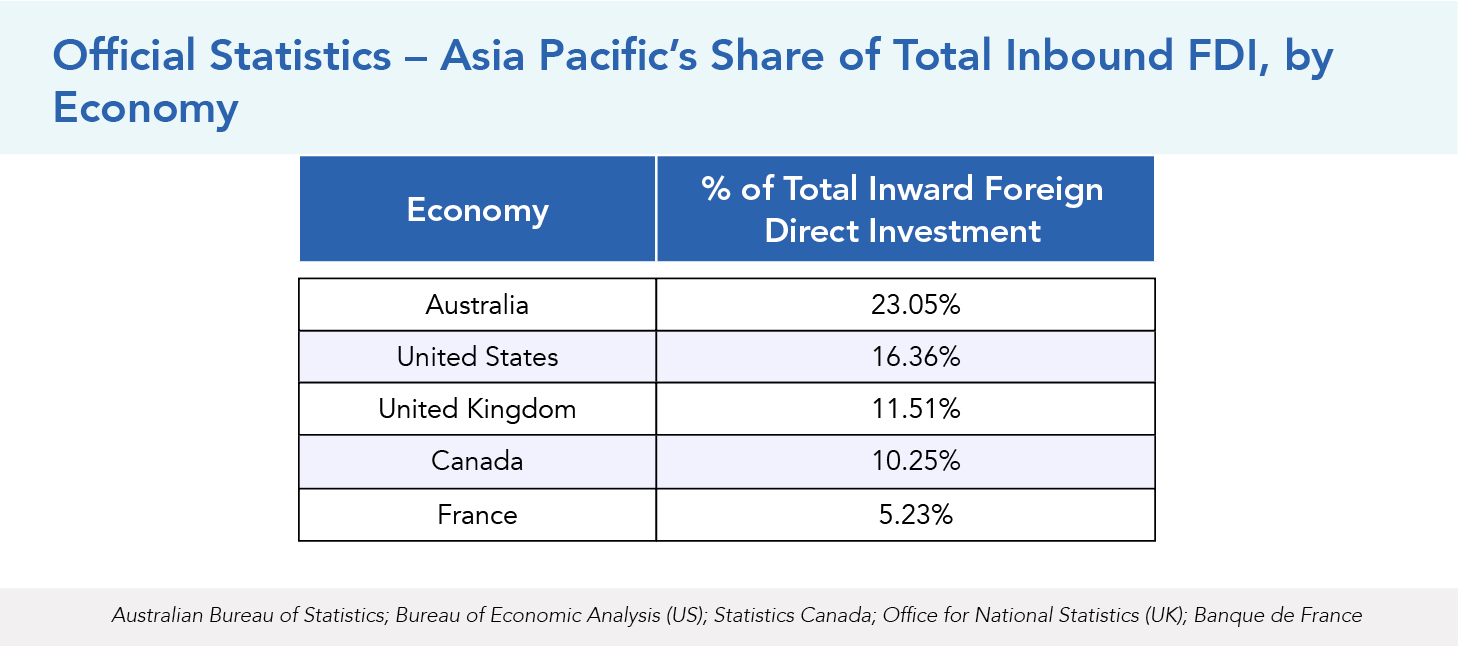

HOW CANADA STACKS UP IN ITS INVESTMENT RELATIONSHIP WITH THE ASIA PACIFIC

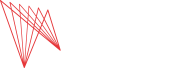

Canadian outward direct investments are highly concentrated in traditional economic partners. Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States accounted for almost 80 percent of Canadian FDI stocks in 2018. The United States, in particular, remains Canada’s top investment destination: in 2018, Canada’s southern neighbour accounted for 46 percent of Canada’s outward foreign direct investment stock with C$595B of value, a 13 percent increase from the previous year. Europe and the United Kingdom, on the other hand, accounted for 33 percent of Canadian investment stock. Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific region remains limited: in 2018, the region accounted for 6.9 percent of Canada’s total outward FDI stock, a 0.4 percent drop from 2017 data.

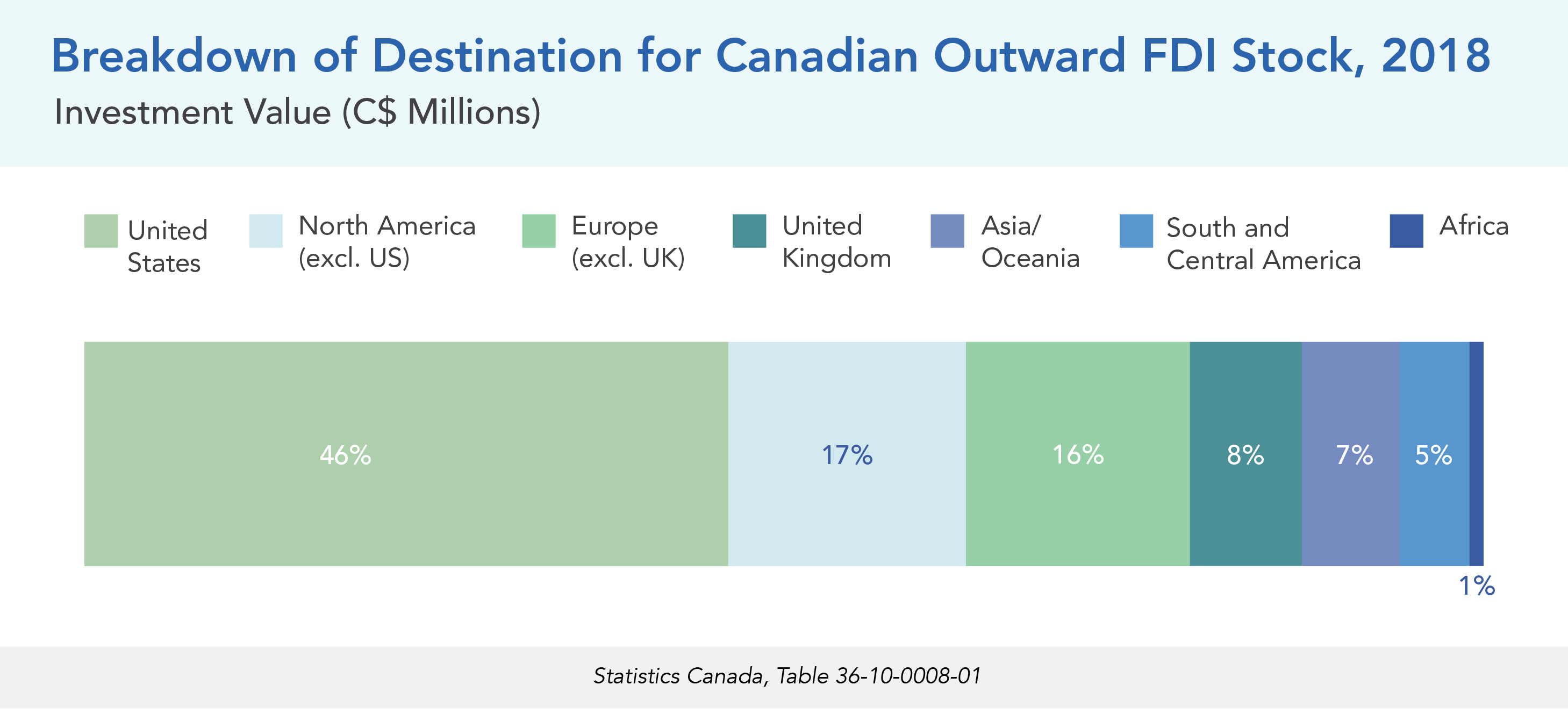

When it comes to the economy’s share of total investment from the Asia Pacific, Canada ranks low compared to many comparator economies, including Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. The average proportion of their Asia Pacific investments in 2018 was 14 percent, and Canada was about 4 percentage points below the average. This suggests that there remains room for Canada to improve investment ties with the region.

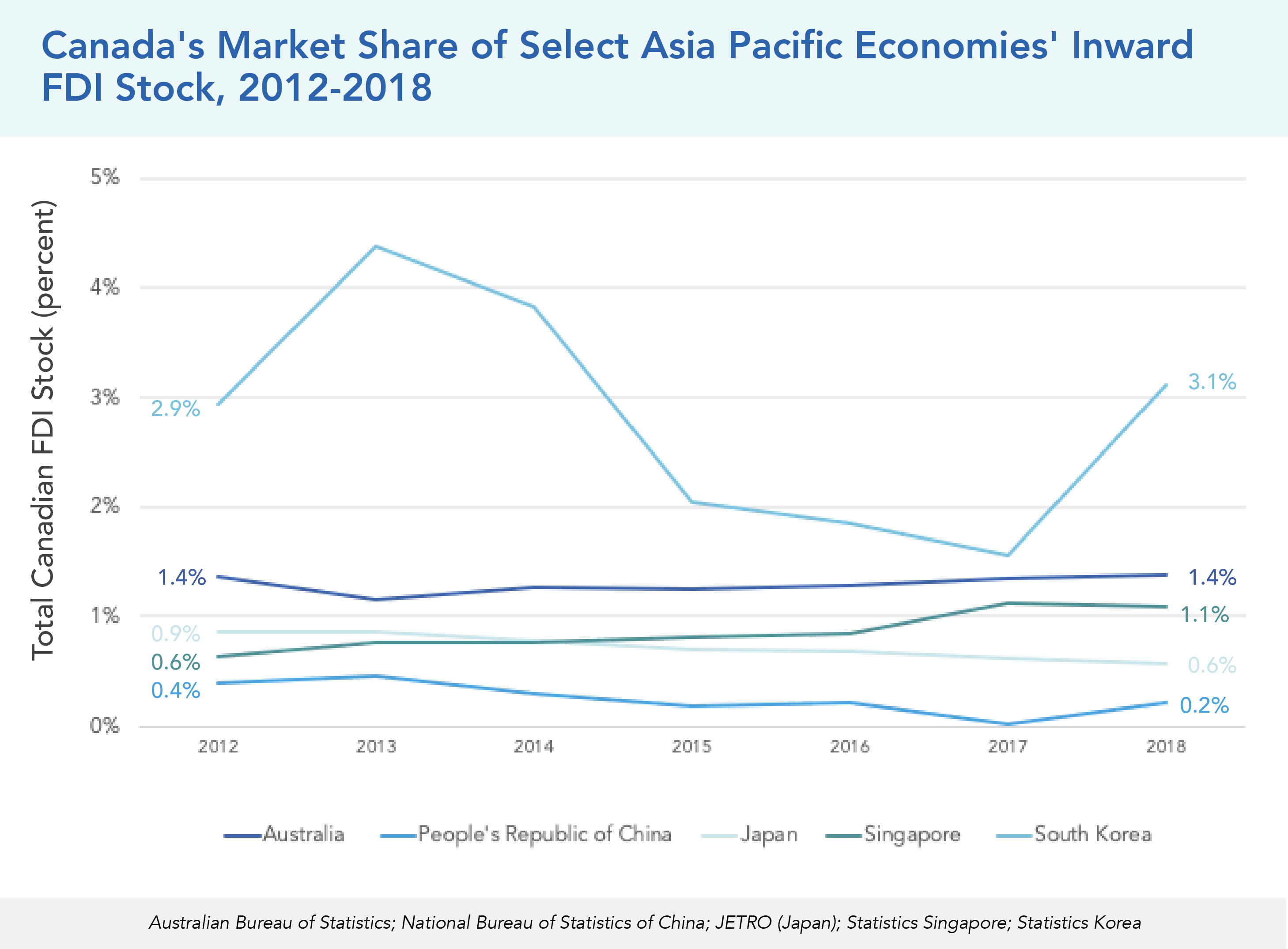

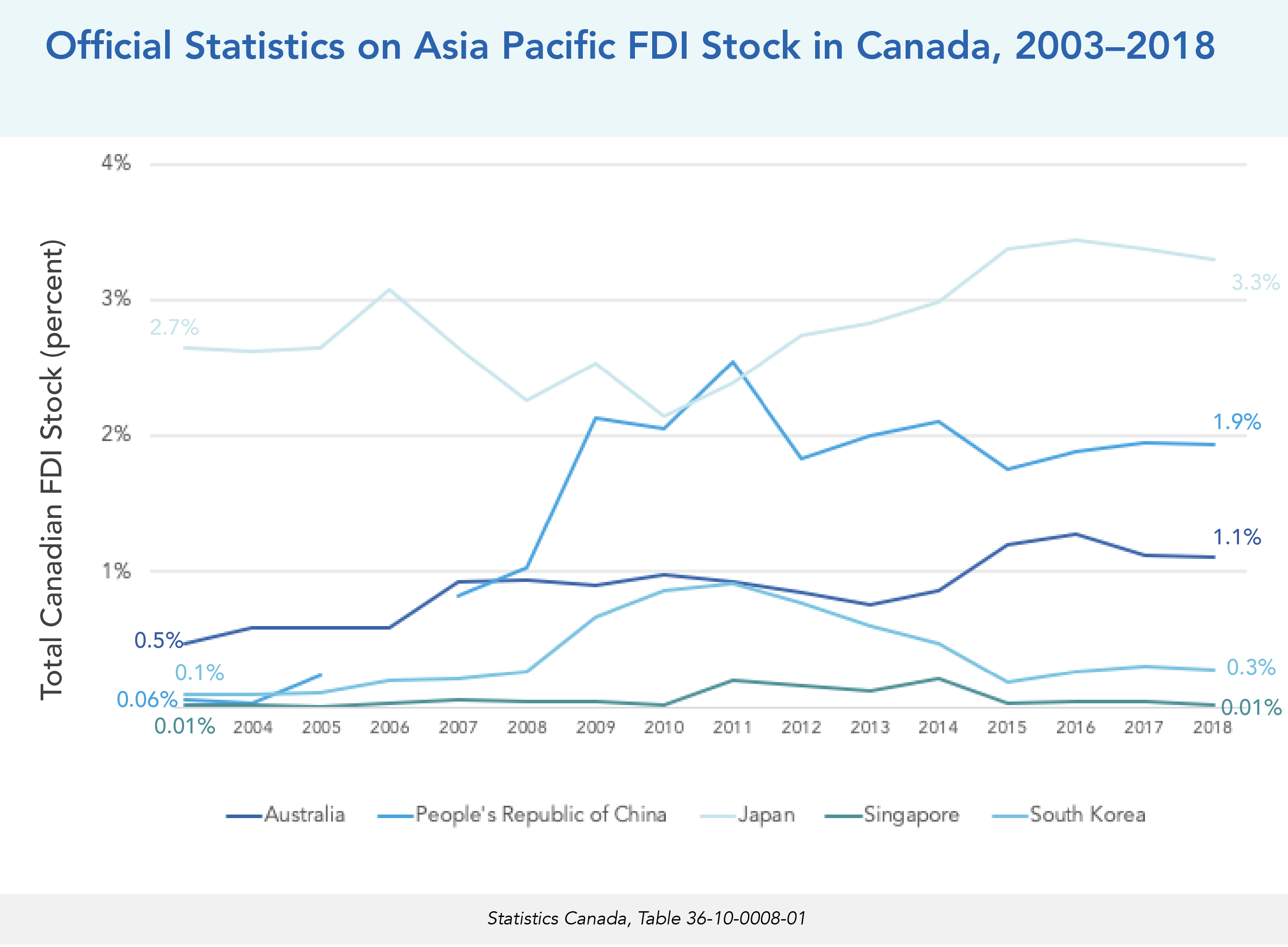

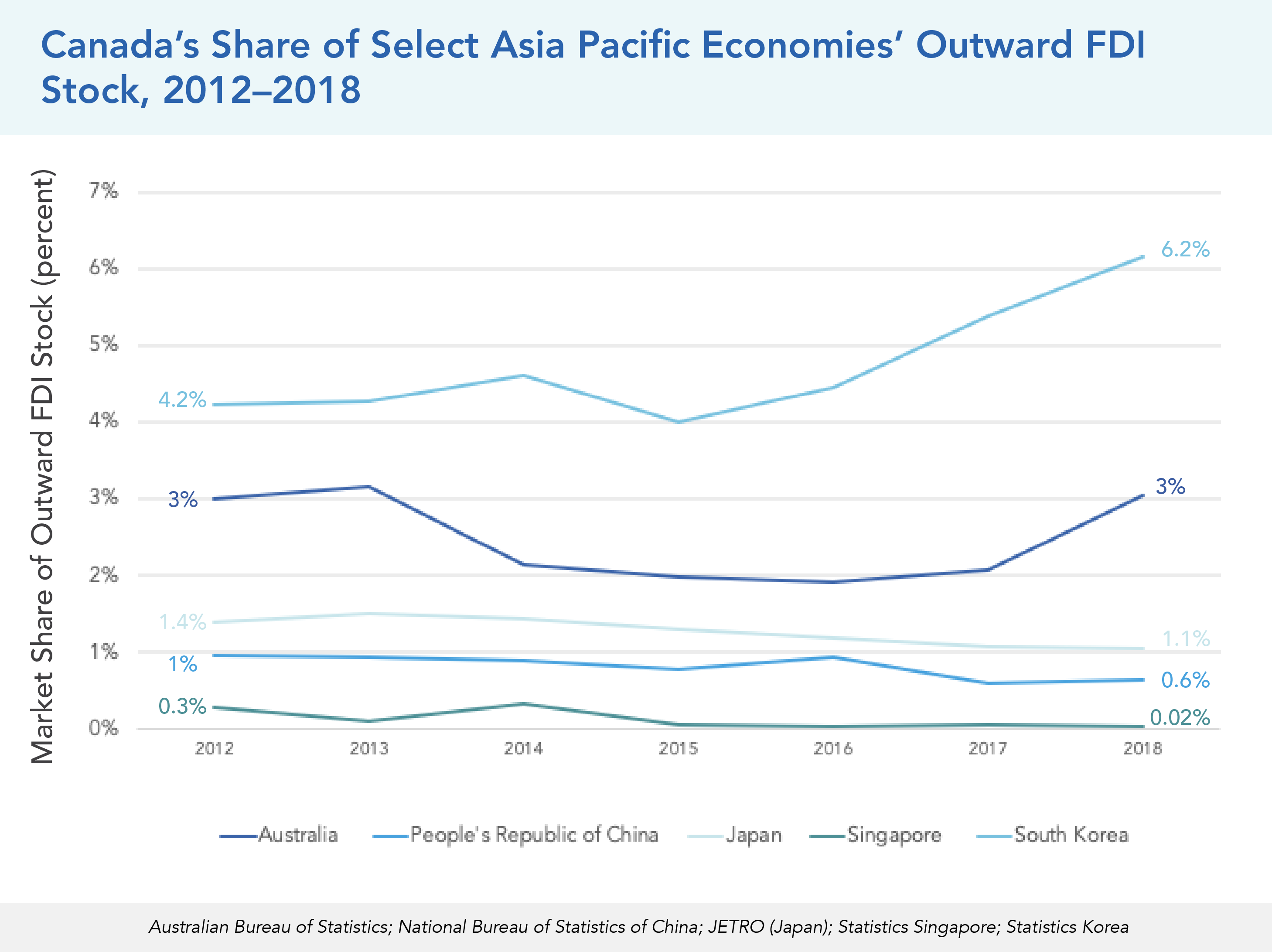

Canada’s role as investor in the Asia Pacific remains small, both as a share of Canada’s total outward investment and as a share of investment received by Asia Pacific economies. As of 2018, Canadian investment in the region totalled C$88.9B, or 10 percent of all Canadian investments abroad. Some of the most invested-in economies in the region are Australia, China, Hong Kong, and Japan, which have shares of total Canadian outbound flows ranging from 0.5 to 2.4 percent. Inbound investments from the Asia Pacific are also small, but have been generally stable since 2015. Japan notably has the highest relative share of inbound investment into Canada, while Singapore has the lowest share. Official statistics from economies across the Asia Pacific similarly show that Canada is a small investor in the region. Data from 2018 for Australia, China, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea show that Canada’s share in their inward FDI flows ranged from only 0.2 to 3.1 percent.

For investment coming into Canada, these statistics also show that Canada is not a significant destination for the Asia Pacific. One notable exception is South Korea, where outward FDI to the Canadian market is steadily rising.

The official statistics provided by Statistics Canada show Canada’s international investment position on a national level, using a top-down approach in its collection of data. The data is mainly gathered from surveys of Canadian and foreign firms, as well as reports from government bodies like the Bank of Canada.

Due to the top-down nature of the data, Statistics Canada is unable to record the ultimate sources and destinations of investments, the subnational-level distribution of investments, and the distribution of investments by industry. As such, national data provided by Statistics Canada and Asia Pacific economies does not offer transaction-level information on FDI, nor details on the number of deals and distribution of investments across geographic regions and industries.

BOX 2. CROSS-BORDER INVESTMENT AND FDI

Cross-border investments can be separated into two major groups: 1) foreign portfolio investment (FPI) and 2) foreign direct investment (FDI).

Foreign Portfolio Investment

FPI is a temporary investment by a resident or enterprise of one economy into a financial asset of another economy. This investment involves a non-controlling stake in an enterprise in the form of equity, debt securities, or loans. For example, a Canadian firm increasing its stake from 3 percent to 5 percent in a South Korean firm would be an FPI.

Foreign Direct Investment

FDI is a long-term or lasting-interest investment by a resident or enterprise of one economy into a tangible asset of another country. This type of investment is deemed “long term” or of “lasting interest” if it is either a greenfield investment or an acquisition of at least 10 percent of the equity or voting shares of an enterprise. This 10 percent threshold is considered a controlling interest in an enterprise and is what primarily distinguishes FDI from portfolio investment, since it usually coincides with a transfer of management, technology, and organizational skills along with capital. One example of FDI is Canada-based Gildan Activewear’s investment of $45M into a new manufacturing plant in another country that would expand its textile and sewing operations in the country.

The concepts of stock and flow are commonly used in economics and accounting. Stock refers to an existing quantity at one specific time, whereas flow refers to the movement of quantities in and out of the stock. There are two types of flows: inflow, which is an addition to the stock, and outflow, which is a deduction from the stock. The numerical difference between the inflow and outflow is called a net inflow. If the net inflow is positive, this means that the stock is rising, whereas if it the net inflow is negative, this means that the stock is falling. A bank account can illustrate these concepts. The balance of the account is the stock, while deposits and withdrawals from the account are the flows. In an investment scenario, the total amount of capital that Canada has accumulated and depleted through investment over the years is considered the stock. The amount of investment flows coming into and exiting Canada then represent its inflows and outflows, respectively.

[1] Romei, Valentina, and John Reed. 2019. The Asian Century is Set to Begin. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/520cb6f6-2958-11e9-a5ab-ff8ef2b976c7

[2] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2019. World Investment Report 2019: Special Economic Zones. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2019_en.pdf

[3] Pacific Economic Cooperation Council. 2019. State of the Region: 2019-2020. https://www.pecc.org/resources/regional-cooperation/2627-state-of-the-region-2019-2020

[4] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2020. Investment Trends Monitor. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/diaeiainf2020d1_en.pdf

Free Trade Agreements in the Asia Pacific and FDI: Any Correlation?

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

- Free trade agreements have a strong positive effect on boosting foreign direct investment among developed economies. The main causal mechanisms are the additional investment protection clauses included in all agreements, the expanded market, and the lowered costs and barriers for doing business.

- In the Asia Pacific, the strongest evidence for increased FDI after a free trade agreement is the Canada-South Korea free trade agreement signed in 2015. Canada received an additional C$870M from 2015 to 2019.

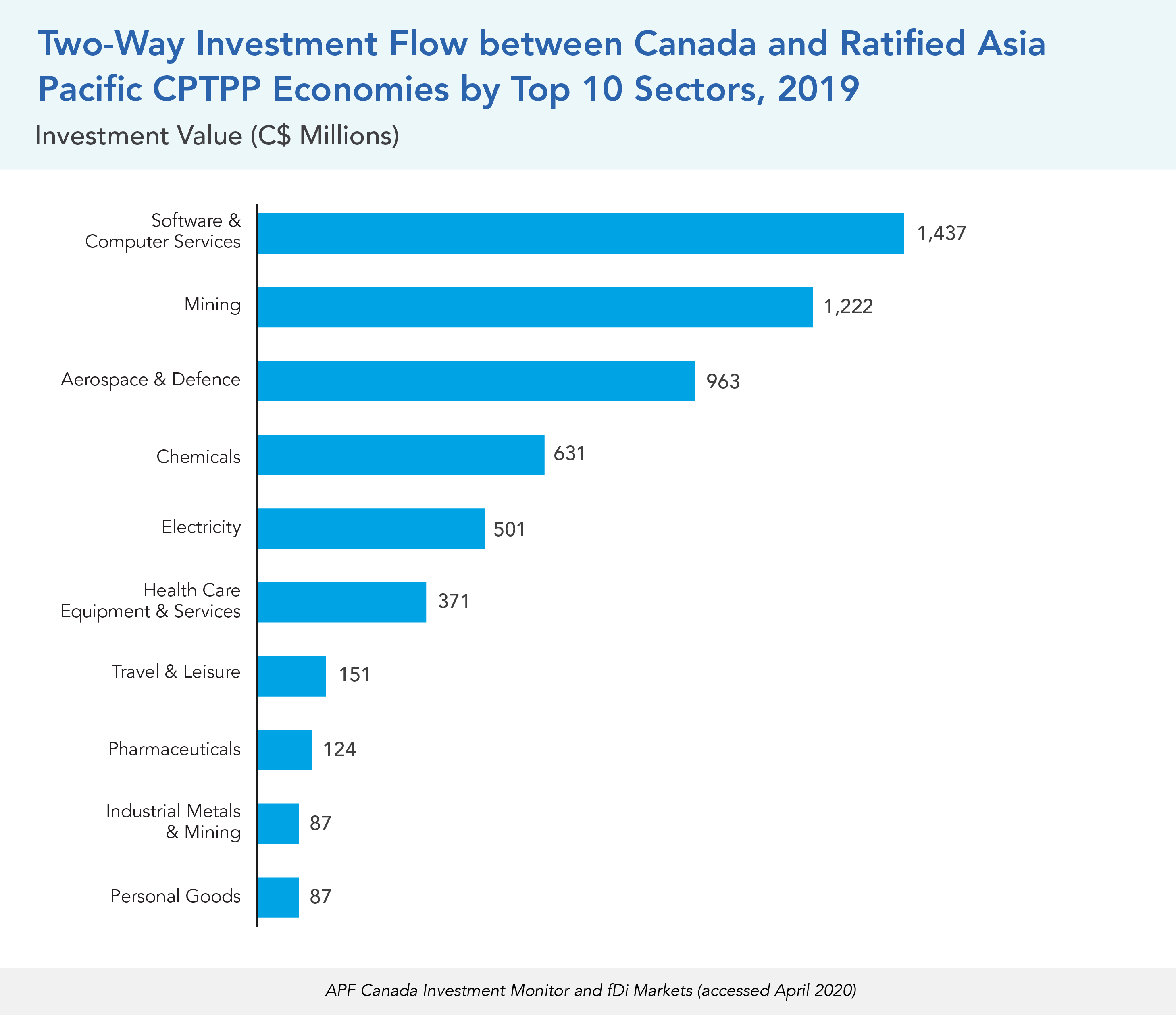

- In 2019, two-way investment flows between Canada and the CPTPP economies were mostly tied to the software and computer services sector, which accounted for 25 percent (C$1.4B) of the total value of inward and outward investment. The next two biggest sectors were mining (C$1.2B) and aerospace and defence (C$963M).

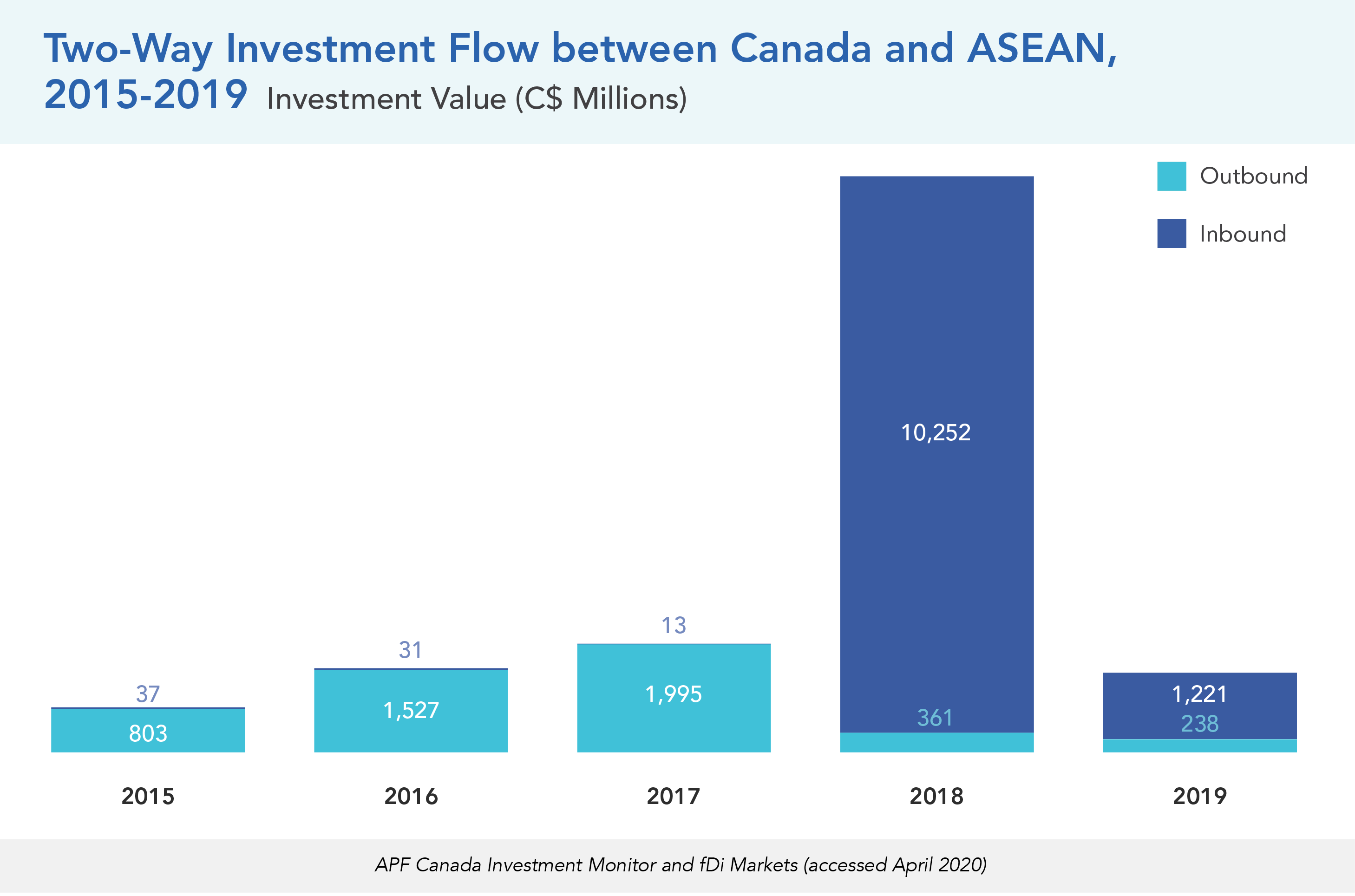

- In 2019, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) economies invested over C$1.2B (12 deals) in Canada, whereas Canada invested C$112M (8 deals) into ASEAN.

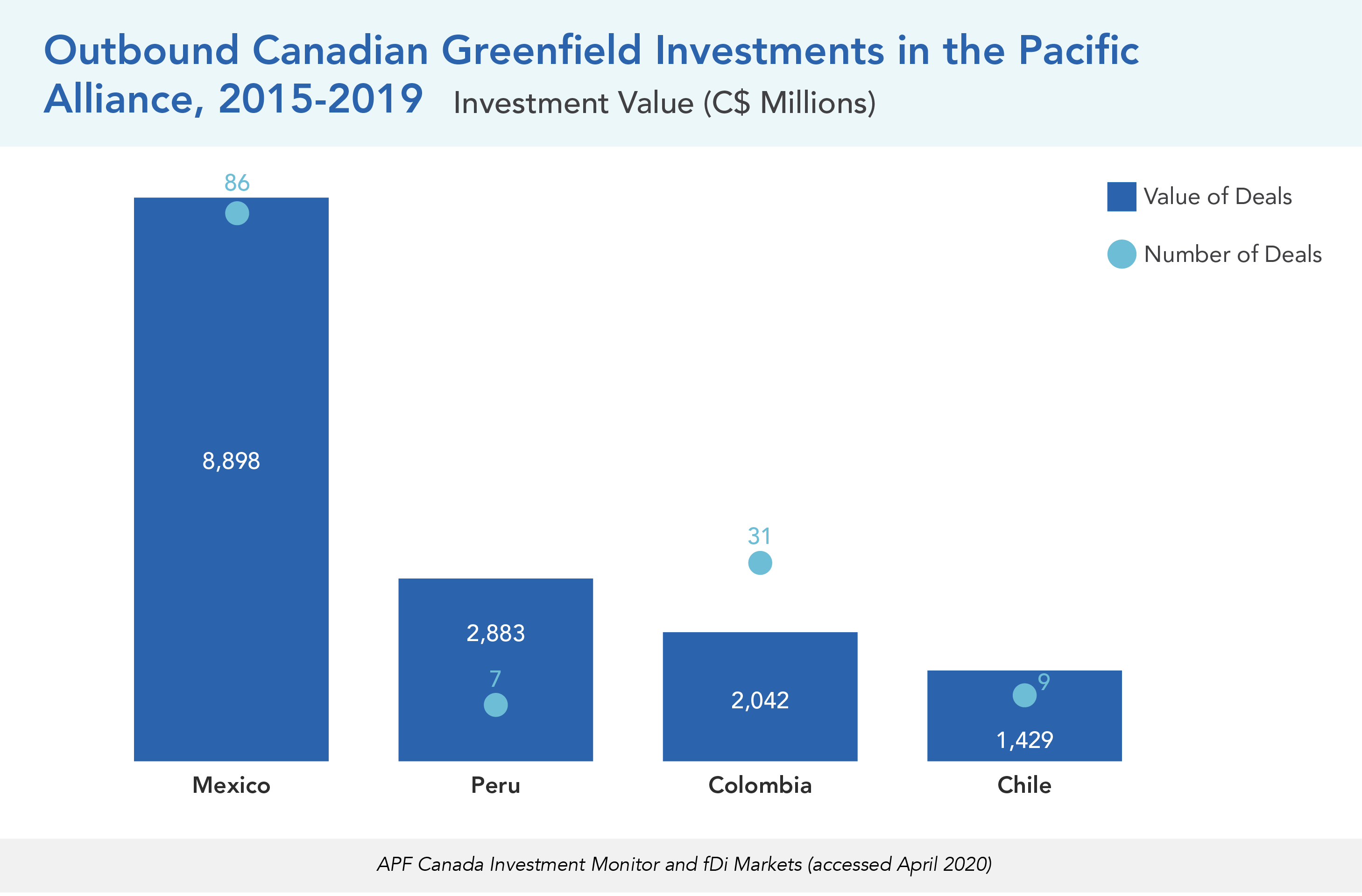

- In the past five years, Canadian companies have been investing in greenfield deals in the economies of the Pacific Alliance, with a cumulative investment value of C$17.1B.

FDI AND TRADE THEORY

In this report, APF Canada decided to explore one of the most common questions about foreign direct investment: What is the relationship between FDI and trade, and more specifically free trade agreements? Since the 1990s, economic theory and research has been conducted on if and how increasing bilateral investment treaties and free trade agreements heightens investors’ confidence by securing equal treatment, respect for international norms, and rule of law, including protection of the right to profit and capital repatriation.[5] The proliferation of free trade agreements after the 2000s put this theory to the test. Different studies have proved that there are not one, but numerous causal mechanisms behind the strong relationship existing between FTAs and foreign direct investment, depending on the size of the market, the levels of commercial exchange, and the possibilities of expansion.[6]

The first and most important incentive for investment as a result of an FTA is the enhancing credibility of the chapter on investment protection that is included in every FTA. Investment protection chapters now not only prohibit expropriation without prompt and adequate compensation, but they also prohibit discriminatory treatment toward foreign investors. In addition, all FTAs, as well as most bilateral investment treaties (BITs), offer the additional benefit of settling any international investor-state dispute through third-party arbitration and other dispute-settlement mechanisms.

These benefits provide levels of guarantees that help investors feel safe moving in and out of the member countries in the new agreement. They reassure the investor that the host country will eliminate production distortions and procedural or institutional barriers to conducting business in that country.[7] For the Canadian economy this is significant because FTA investment protection chapters have protected one of its most important investment sectors, mining and extractive industries, whose products are usually not covered by tariff reductions.

Other scholars have found that the potential size of the market induced investment in local production and incorporation in core value chains of the most developed country.[8] For instance, South Korea’s FDI in greenfield investments and advanced manufacturing expanded rapidly with FTA partners because of the added value of bilateral tariffs over time.[9] Trade openness offers additional incentives for South Korean companies as they use the agreements to expand manufacturing facilities and create economies of scale. Our own findings suggest this relationship in the case of South Korea, as Canada’s investment in South Korea increased almost threefold after the ratification of the FTA. While Korean investment in Canada was already significant, it increased even more after the agreement. Korea’s wide manufacturing base and Canada’s large market provided additional incentives, but the FTA explains at least 50 percent of the additional investment Canada received from this new partnership.

Mega free trade agreements tend to provide further incentives to increase foreign direct investment. Jang has shown that, at least for developed countries like Canada, the existence of a regional FTA increased FDI by 14 to 35 percent from member countries alone and by 28 to 35 percent from non-member countries.[10] Multilateral and plurilateral trade agreements such as the CPTPP can create additional incentives, such as regional market integration and regional supply chains in both goods and services, which make investment flows easier and more attractive. In other words, these mega agreements not only enhance investors’ confidence in a common set of rules and legal protections for investments, but also in the fluidity and increase in labour services, equity markets, financial services, innovation, and technology that become available when distance stops being an issue.

In sum, FTAs are potentially better at increasing foreign direct investment – rather than trade – in the new member countries, at least in the first five years after ratification.[11] Increasing investment protection, national treatment, expanded market possibilities, and implicit economic co-ordination compound the incentives that boost FDI in new FTA partners, even before the agreement enters into force. The Investment Monitor 2020 report presents only an example of what Canadians should observe about the relationship between FTAs and foreign direct investment inward and outward. We start by analyzing the deals and investment in the largest free trade agreement in the Pacific, the CPTPP, and then look at the Canada-Korea Free Trade Agreement (CKFTA). For comparative purposes, this chapter will also examine Canada’s investment ties with the ASEAN economies and the Pacific Alliance FTA under analysis by the Canadian government.

FTAS AND INVESTMENT

The Comprehensive Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership

The CPTPP was signed in March 2018 between Canada and 10 other economies in the region, and entered into force on December 30 of the same year. As of April 2020, the trade agreement has been ratified by seven economies, including Australia, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam.[12]

The CPTPP was first implemented in 2019, but this was a difficult year for the global economy and the Asia Pacific region in particular. The US-China trade dispute derailed many trade and investment opportunities on both sides of the Pacific, and it is difficult to assess to what extent the trade war influenced the final investment outcome compared to the opportunities lost.

The total two-way value of Canadian investment with economies that ratified the CPTPP was C$5.8B (56 deals). In particular, outward and inward Canadian investments were valued at C$2.95B (25 deals) and C$2.9B (31 deals), respectively. The biggest inbound investment deal of 2019 into Canada from the CPTPP was a C$731M deal from Tokyo-based Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. to acquire the Canadair Regional Jet Program from Bombardier Inc. Meanwhile, the biggest outward Canadian investment transaction was a C$917M investment from Toronto-based Brookfield Asset Management Inc., acquiring a 49 percent stake of Vodafone New Zealand Limited.

Canada and five other economies in the region have ratified the CPTPP, including Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and Singapore. Overall, the investment flows for 2019 between Canada and CPTPP-ratified economies decreased from 2018. However, in 2018, there were a few deals that dominated the share of total investment flow. Of these high-scale deals, state-owned enterprises such as the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System and the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board had the lion’s share (over 50 percent) of investments into the Australian real estate and mining sectors. These pension-backed enterprises from Canada invest in a diverse range of assets in public and private sectors worldwide.

Similarly, the volume of inward Canadian investment in 2018 was dominated by a few investment deals. Over three-quarters of the total inward investment (C$6.1B) was from Japanese Mitsubishi Corporation through its joint venture, LNG Canada, into the oil and gas producers’ sector of Canada, building a liquefied natural gas export facility in BC. LNG Canada is a joint venture among Shell Canada Energy, Petronas, PetroChina Company Limited, Mitsubishi Corporation, and Korea Gas Corporation.

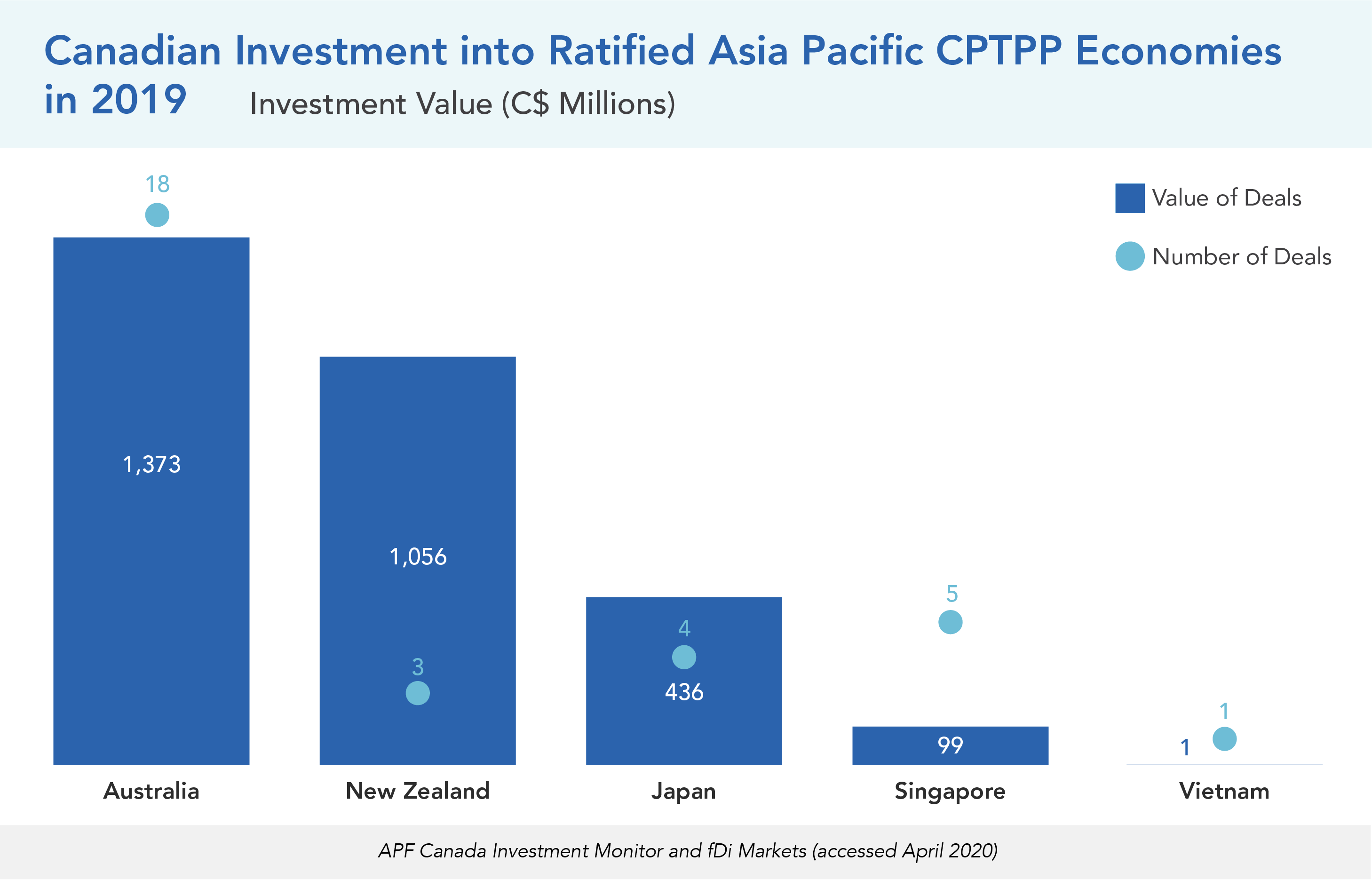

Within the CPTPP economies, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan were the top investment destinations for Canada in 2019. Canada invested over C$1.4B (18 deals) into Australia, C$1.1B (3 deals) into New Zealand, and C$436M (4 deals) into Japan. The target investment sectors in Australia were diverse, with chemicals (C$623M), health care equipment and services (C$335M), and travel and leisure (C$150M) at the top. On the other hand, New Zealand’s software and computer sector attracted the most Canadian investment (C$1B) to the country. Canada invested in Japan’s utilities sector (C$436M), particularly in alternative electricity.

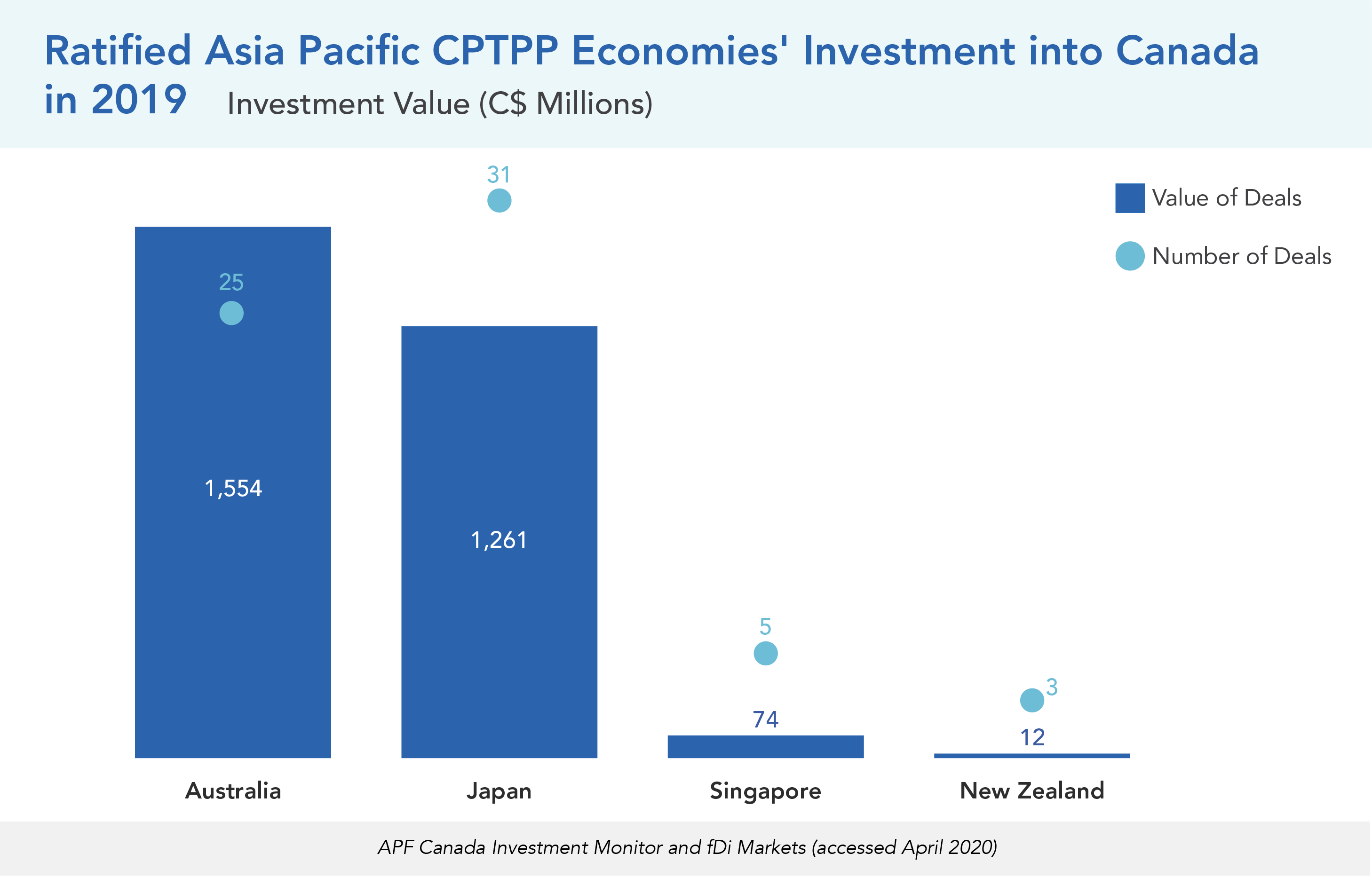

In terms of Canadian inward investment from the CPTPP economies in 2019, Australian investment into Canada amounted to over C$1.5B (25 deals), and Japan invested C$1.3B (31 deals). The majority of Australian investment (C$1.2B) went to the mining sector of Canada, while a big share of the Japanese investment (C$933M) was in the aerospace and defence sector.

Overall two-way investment with Australia is the highest in both scale (C$2.9B) and number (43 deals) of deals among the CPTPP-ratified economies, whereas Japan is the second-largest investing partner with Canada, accounting for C$1.7B in 35 deals in 2019. Moreover, New Zealand had only six deals in both inward and outward investments with Canada, but their value was quite high (C$1.1B) compared to the number of deals.

Two-way investment flows between Canada and the CPTPP economies were mostly tied to the software and computer services sector, which accounted for 25 percent (C$1.4B) of the total value of inward and outward investment in 2019. The next two biggest sectors were mining (C$1.2B) and aerospace and defence (C$963M). While the former accounted for 21 percent, the latter accounted for 16 percent in the last year. Other sectors did not receive as much investment as these three sectors received in 2019.

Canada-Korea Free Trade Agreement

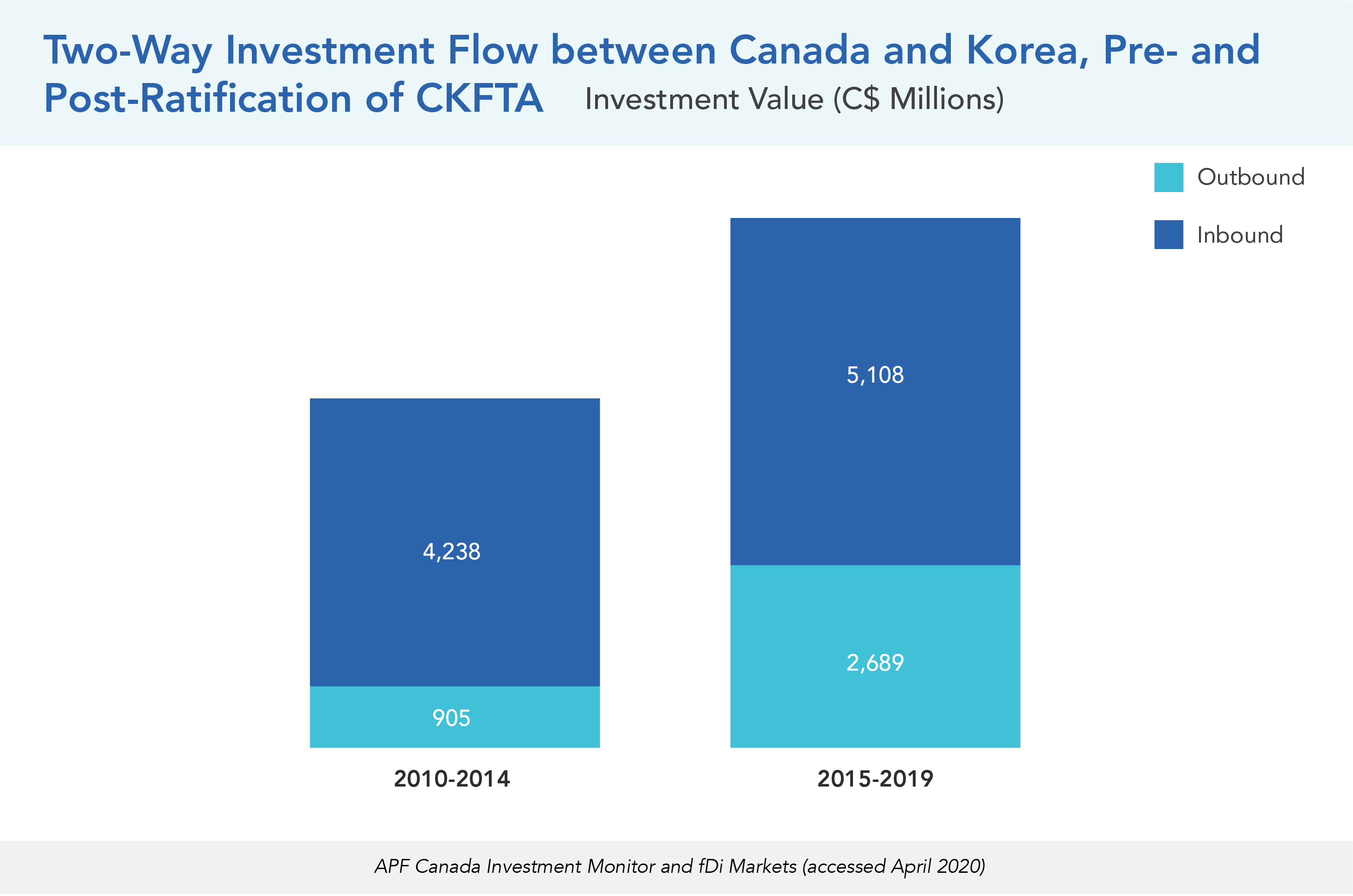

Canada and South Korea signed their free trade agreement in 2014, and the treaty came into force in January 2015. The CKFTA contains protection clauses that aim to set out a more transparent and predictable environment for both Canadian and Korean investors.[13] After the CKFTA was ratified, there were a total of 37 investment deals between the two countries, and the value of the two-way investment flow was C$7.8B between 2015 and 2019.

Although it has been only five years since the ratification, the value of total two-way investment flows in the period increased significantly, by 35 percent, from C$5.1B to C$7.8B. Compared to the preceding period (2010-2014), the number of total deals made between Canada and Korea increased by 16 percent, from 31 deals to 37 deals.

Over the last 10 years, Korean investment into Canada has consistently surpassed outbound Canadian investment into South Korea. Within the previous five years, inbound investment from Korea rose by 17 percent, reaching C$5.1B, from C$4.2B (2010-2014). On the other hand, interest in the Korean market by Canadian businesses surged after ratifying the FTA, reflected by the number of deals and the value of investments made from Canada to Korea. Canada invested over C$2.4B between 2015 and 2019, a 63 percent increase compared to the pre-ratification period. There were 13 deals from Canada to Korea from 2015 to 2019, while there were only nine deals in the previous five years. This growth is consistent with what the theory predicted about the positive effect of FTAs in boosting foreign direct investment for new partnerships.

In terms of sectors, Canadian investment into South Korea in the last five years focused on a few main sectors, including general retailer (28 percent), real estate investment and services (26 percent), electronic and electrical equipment (22 percent), and industrial transportation (13 percent). Two of the largest investment deals into South Korea were from one source, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB). In the year the CKFTA was ratified, the CPPIB invested over C$763M in one of the largest retailers in Korea, Homeplus. Also, in 2018, the pension fund invested C$250M to own a 50 percent stake in real estate located in the centre of Seoul, the Kumho Asiana Main Tower. The CPPIB has stated that its investment in the Korean real estate sector reflected its desire to enhance the firm’s investments in the Asia Pacific region as well as its strategy to invest in top-tier, well-located properties.

In the previous five years, inbound investment from South Korea was worth C$5.1B. Of this C$5.1B, 43 percent went into the oil and gas producers sector, 32 percent into the industrial engineering sector, 8 percent into the pharmaceuticals sector, and 5 percent into the construction and materials sector of Canada. The biggest investment deal made in the oil and gas producers sector was C$2B from Korea Gas Corporation, which entered the Canadian market through its joint venture, LNG Canada, in 2018. In the same year, Korean Hanon Systems invested over C$1.6B to acquire the fluid pressure and controls business of Magna International Inc., an Ontario-based auto parts company.

LOOKING AHEAD: CANADA’S INVESTMENT TIES WITH ASEAN AND PACIFIC ALLIANCE ECONOMIES

Canada and ASEAN

ASEAN is one of the world’s fastest-growing economic regions, including Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. According to the 2019 ASEAN Economic Integration Brief, the economic growth rate of ASEAN was 5.1 percent in 2018, compared to 3.6 percent of the world growth rate. From 2003 to 2019, two-way investment between Canada and ASEAN accounted for only 13 percent of total investment between Canada and the Asia Pacific, still lagging behind the other Asia Pacific economies. Therefore, both a gap and an opportunity exist for Canada to strengthen its two-way investment ties with ASEAN and other emerging economies.

In 2019, the ASEAN economies invested over C$1.2B (12 deals) in Canada, whereas Canada invested C$238M (11 deals) in ASEAN. Those 12 deals from ASEAN economies in 2019 marked a significant increase in activity, up from seven deals for the four years prior combined. The source of investing economies (Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand) became more diversified in 2019. Before 2019, there were only one or two economies of ASEAN, such as Singapore and Malaysia, invested in Canada. One of the sources that became active in the Canadian market in 2019 was Bangkok-based Charoen Pokphand Group, which acquired Manitoba-based HyLife for C$498M. HyLife operates in the fishing and animal production sector, focusing on producing and supplying pork products.

On the other hand, Canadian investment in the ASEAN economies shrank both in the value of investment and in the number of deals from the previous four-year period. The majority of Canadian investment to ASEAN in 2019 was in the Philippines, which accounted for 52 percent (C$124M) of the total Canadian outbound investment in the ASEAN economies. There were two big deals made into the Philippines’ financial market out of a total of 11 outward investment deals from Canada.

Although total two-way investment decreased significantly in 2019, the reason for the large amount of investment inflows into Canada in 2018 was one deal from a Malaysian state-owned enterprise, Petronas. The deal, which saw C$10B invested in LNG Canada, was the biggest investment made in Canada from the ASEAN economies between 2003 and 2019.

Canada and the Pacific Alliance

The Pacific Alliance is a regional economic bloc composed of Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, established in 2011. The Alliance was formed to deepen the integration between the members, promoting free trade in goods and services and increasing mobility of capital and labour within the bloc. In June 2017, Canada was invited to be an Associated State of the Pacific Alliance, which required it to begin the negotiation of an FTA with the bloc. The negotiation between Canada and the Pacific Alliance is still ongoing.[14]

In 2019, Canadian investment value in the Pacific Alliance was over C$2.6B, made through 37 greenfield investment deals. Of the total Canadian investment in the Alliance, C$1.2B (48 percent) flowed to Mexico through 18 deals, and C$678M (26 percent) went to Peru through 3 deals. Considering Colombia’s inward investment from Canada, despite a high number of deals (14 deals), the total amount of the investment barely reached C$644M. Meanwhile, Chile had only two investment deals from Canada in 2019, which accounted for C$4M. The biggest outbound deal in 2019 to the Pacific Alliance was by Vancouver-based PPX Mining Corp. in the mining sector of Peru to build a heap leach gold and silver processing plant, valued at C$655M. Meanwhile, there was only one inbound deal (C$12M) made in greenfield investments in 2019 from the Alliance, which was from Mexico to the Canadian software and computer service sector.

Over the past five years, Canadian investment in Pacific Alliance economies had a cumulative value of C$17.1B, and the investment flow trend has fluctuated. A majority of Canadian outbound investment in the Alliance went to Mexico, valued at over C$8.9B (86 deals). The second most popular investment destination in the Alliance for Canadian business was Peru, with over C$2.9B invested (7 deals), the third was Colombia, valued at C$2B (31 deals), and the last was Chile, with C$1.4B (9 deals) between 2015 and 2019. Despite the significant flow of Canadian investments into the bloc, the reverse flow of investment has not occurred, except for sporadic Mexican investments into Canada, which were valued at C$56M (4 deals) from 2015 to 2019. The reason for the higher investment scale between Canada and Mexico is that these two countries have a long-term partnership rooted in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), while the other economies have only recently partnered with Canada. The additional reason is that the positive effect of FTAs on investment is stronger in developed economies and weaker when the partnership includes developing ones. Even when an FTA provides the same clauses for investment protection, the realities on the ground and the size of the market works against a stronger benefit for the developed economy, while the benefit is still there for the developing one.[15]

USAGE CHALLENGES AND FUTURE PROMISES

In all, the CPTPP adds an additional positive effect, as predicted by the theory. Within the Pacific Alliance, the economies of the CPTPP are the top investment partners of Canada in terms of the number of deals and the value of investments. Although the investment volume with the CPTPP did not increase after the FTA ratification, it is still too early to determine the potential of the FTA based on the one-year investment flows between Canada and the CPTPP.

On the other hand, the CKFTA has showed a significant increase in the number of deals as well as the value of investments between Canada and South Korea over the past five years. Thanks to the FTA, opportunities were provided not only to South Korea to increase its investment into Canada, but also to Canadian businesses to expand their investments in the South Korean market. Meanwhile, Canadian investments with ASEAN and the Pacific Alliance showed inconsistencies in investment trends, because Canada’s investment flows were often distorted by high-scale transactions, particularly in inbound investments with ASEAN in 2018. However, with the Pacific Alliance, the two-way flow in greenfield investments was mainly composed of outbound Canadian investment, the majority of which went to Mexico based on their relatively long-term partnership through NAFTA.

The Pacific Alliance represents a promise for Canadian foreign direct investment that needs to be monitored and understood in the future as Canada moves closer to securing a free trade agreement with the bloc. The economies of scale, especially in the energy and mining sectors, can be multiplied with an enhanced trade ecosystem that involves the Canadian service sector.

[5] Guzman, Andrew T. "Why LDCs sign treaties that hurt them: Explaining the popularity of bilateral investment treaties." Va. j. Int'l L. 38 (1997): 639.

[6] See Moon, Jongchol. "A Study of the Effects of Free Trade Agreements on Foreign Direct Investment." Order No. 3388134, University of California, Los Angeles, 2009. http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/304853969?accountid=14656. Jang, Yong Joon. "The impact of bilateral free trade agreements on bilateral foreign direct investment among developed countries." The World Economy 34, no. 9 (2011): 1628-1651.

[7] Ibid, 5

[8] Kahouli, Bassem, and Samir Maktouf. "The proliferation of free trade agreements and their impact on foreign direct investment: An empirical analysis on panel data." Journal of Current Issues in Globalization 6, no. 3 (2013): 423.

[9] Bae, Chankwon and Yong Joon Jang. "The Impact of Free Trade Agreements on Foreign Direct Investment: The Case of Korea*." Journal of East Asian Economic Integration 17, no. 4 (12, 2013): 417-444.

[10] Jang, Yong Joon. 2011. The impact of bilateral free trade agreements on bilateral foreign direct investment among developed countries. The World Economy. 34.9: 1630.

[11] See our CPTPP Tracker for examples of trade imbalances immediately after ratification. There is also abundant literature about this matter.

[12] Government of Canada. 2020. Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/cptpp-ptpgp/index.aspx?lang=eng

[13] Government of Canada. 2017. Canada-Korea Free Trade Agreement (CKFTA). https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/korea-coree/summary-sommaire.aspx?lang=eng#2

[14] Government of Canada. 2019. Canada-Pacific Alliance Free Trade Agreement. https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/pacific-alliance-pacifique/index.aspx?lang=eng

[15] Jang, op. cit., p. 9.

The National Picture

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

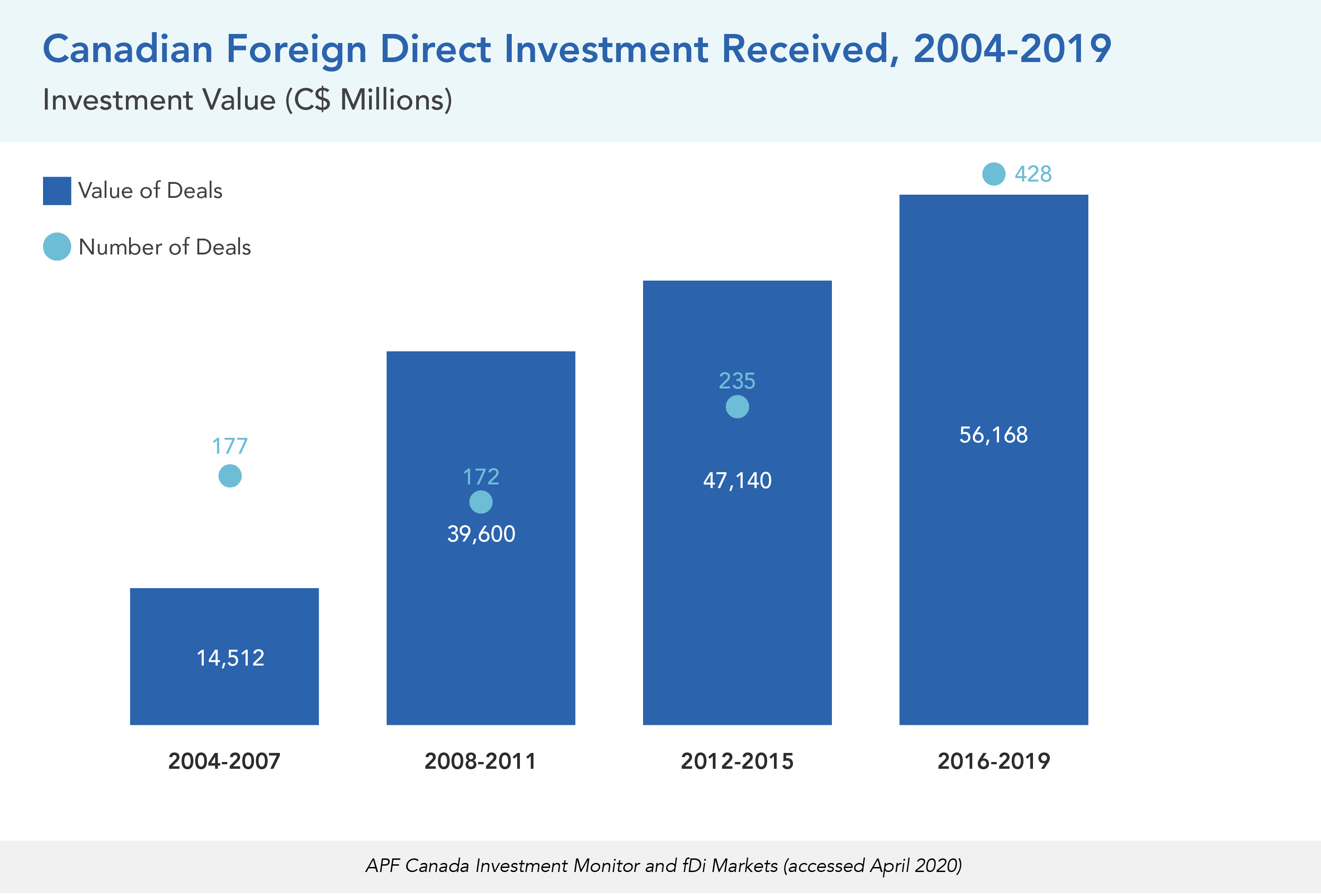

- Between 2016 and 2019, Canada received C$60B in inbound investment from the Asia Pacific through 413 deals, hitting a 16-year high.

- While investments from the Asia Pacific into Canada are still primarily in natural resources, which comprises the energy, mining, and agriculture industries, inbound investments in the technology sector have been increasing, from C$396M from 2008 to 2011, to C$1.7B from 2016 to 2019.

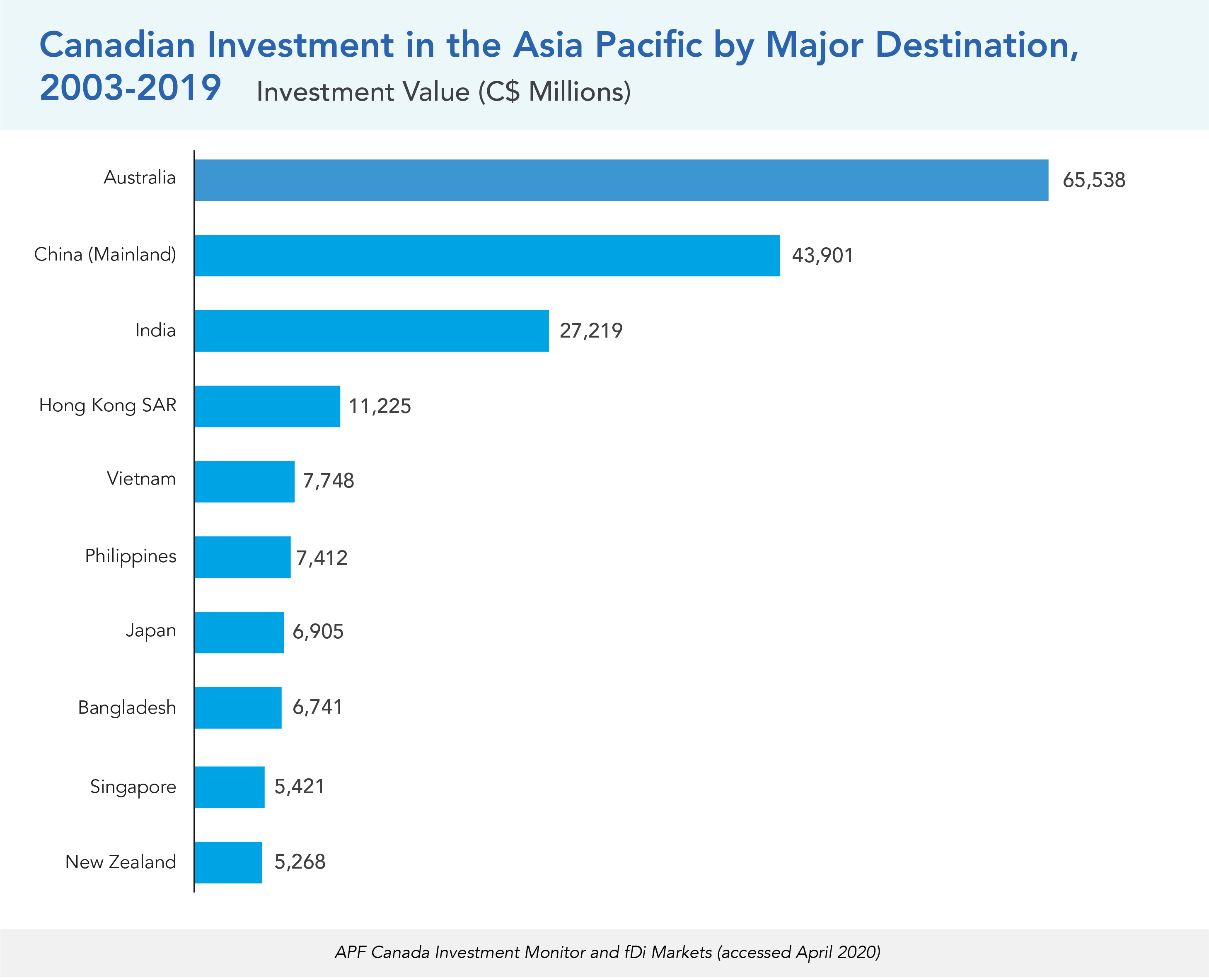

- Since 2003, Australia, China, and India have been the top destinations for outbound Canadian investment into the Asia Pacific. Investment in these economies totalled C$136.7B, accounting for 73 percent of all outbound investment to the region.

- In 2019, 17 percent of Canadian investment went to the automobiles and parts sector, with a dollar value of C$1.3B. Most of these deals involved the establishment of new manufacturing plants for electric cars in China.

INBOUND TRENDS AND PARTNERS IN A YEAR OF RECORD DEALS

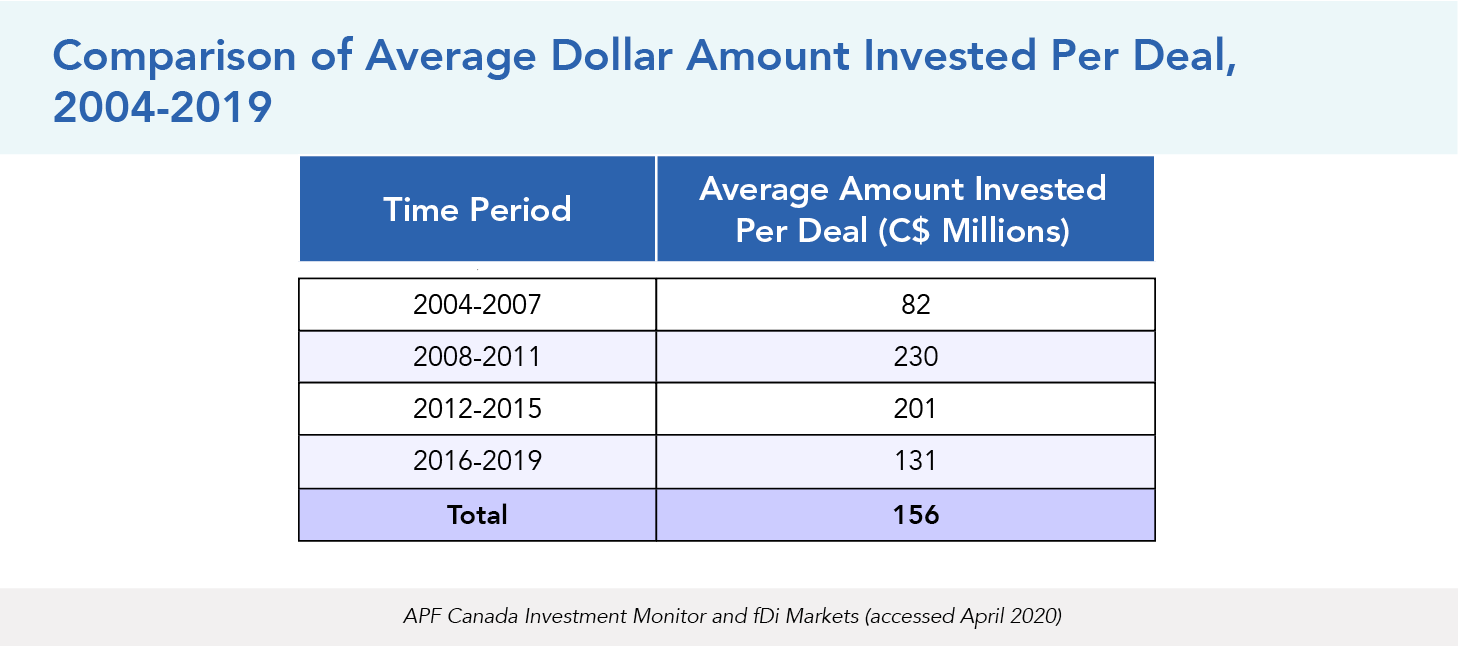

In 2019, Canada received a total of C$8.3B of foreign direct investment from Asia Pacific economies. While it was a drop from the historic high of C$33B in 2018, of which the liquefied natural gas (LNG) project in Kitimat made up close to C$25B, the number of inbound investment deals in 2019 set a record with 151 deals.

From 2015 to 2019, Canada received C$56B of Asia Pacific investment through 428 deals, hitting a 16-year high. Compared to the previous four-year period, inbound investment from the Asia Pacific has jumped by C$9B, or 19 percent. Other than the well-known LNG project in 2018, one of the largest Asia Pacific investments came in 2019, when Jiangxi Copper Corporation acquired PIM Cupric Holdings Limited from Pangaea Investment Management Limited for C$1.5B.[16]

Over the last 16 years, Asia Pacific investment into Canada has been growing both in terms of the investment amount and the number of deals. In this period, APF Canada’s Investment Monitor has captured approximately C$161B in investment through 997 deals. The bulk of the investment came in the last eight years, accounting for 66 percent of the captured investment.

While high-dollar-value investments continue to have significant sway in shaping the total amount of inbound FDI from the Asia Pacific to Canada, the sharp increase in investment deals in the 2016 to 2019 period renders a lower concentration of investment per transaction in comparison to the previous four-year period. The average investment per deal has dropped from C$201M in the 2012 to 2015 period to C$131M in the most recent four years. This figure suggests that while Asia Pacific investment into Canada continues to grow in dollar amount, investment activities ¬– an indicator of investment ties – are increasing at a more rapid pace and smaller-dollar-amount investment forms a growing proportion of inbound investment into Canada.

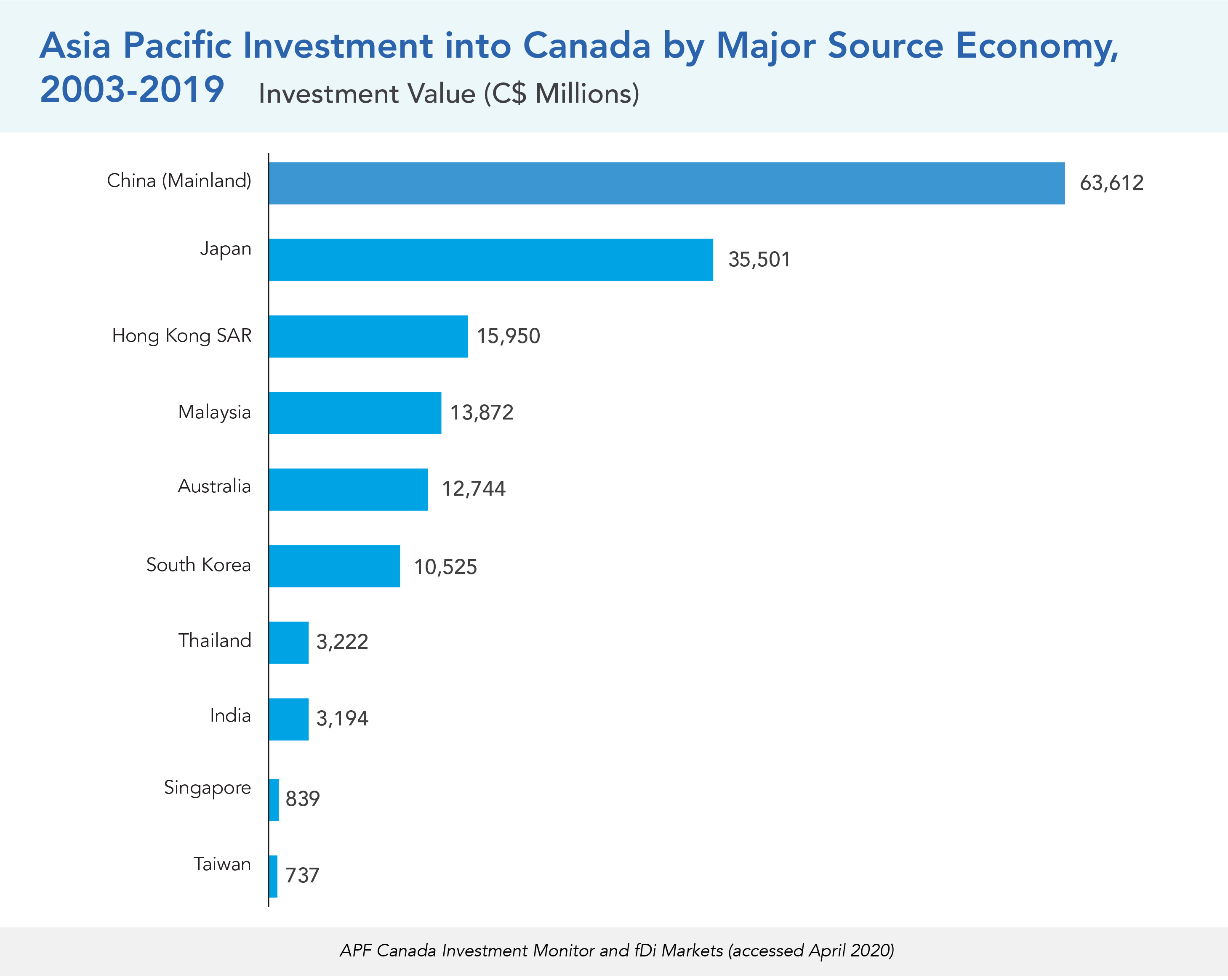

Consistent with previous reports, inbound Asia Pacific investment into Canada has been highly concentrated in a few source economies. The top three source economies alone account for 72 percent of the total Asia Pacific inbound investment into Canada. Over the last 17 years, China remains Canada’s top investor in the region with C$64B injected into Canada’s economy through 275 deals, followed by Japan with C$36B through 292 deals and Hong Kong with C$16B through 74 deals.

China remained the top Asia Pacific FDI source economy for Canada in 2019 with C$3.5B of investment injected into the Canadian economy. The value of new investments from China dropped significantly between 2018 and 2019, with the impact attributable to the significant investment made by China in the LNG project in 2018. Without the China-sourced investment in LNG in 2018, the investment levels between 2018 and 2019 would be roughly the same (C$4.0B and C$3.5B, respectively).

However, China’s investment has subsided in the last four-year period compared to earlier periods. Chinese investment into Canada has decreased from C$27B in the 2012 to 2015 period to C$21B in the most recent four-year period, a C$6.6B, or 24 percent, drop. In comparison to the previous four-year period, Chinese investments are less concentrated in the Canadian oil and gas sector, but China has developed a more diversified portfolio with investments in the mining, real estate investment and services, and health care equipment and services sectors.

Canada has seen dollar-value growth in its inbound Asia Pacific investment from both traditional and non-traditional economic partners. Over the last eight years, investments from Malaysia, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Japan have seen the sharpest increase. The four economies combined represent growth of C$18B when comparing the data between the two most recent four-year intervals. The bulk of the increase is driven by Canada’s oil and gas sector. For Japan, Malaysia, and South Korea, the growth mostly stemmed from their respective investments into the construction of the LNG Canada facility in Kitimat 2018, whereas Hong Kong’s increase can be attributed to CK Hutchison’s C$2.3B investment via Husky Energy into an offshore oil exploration project near St. John’s, Newfoundland, in 2017.

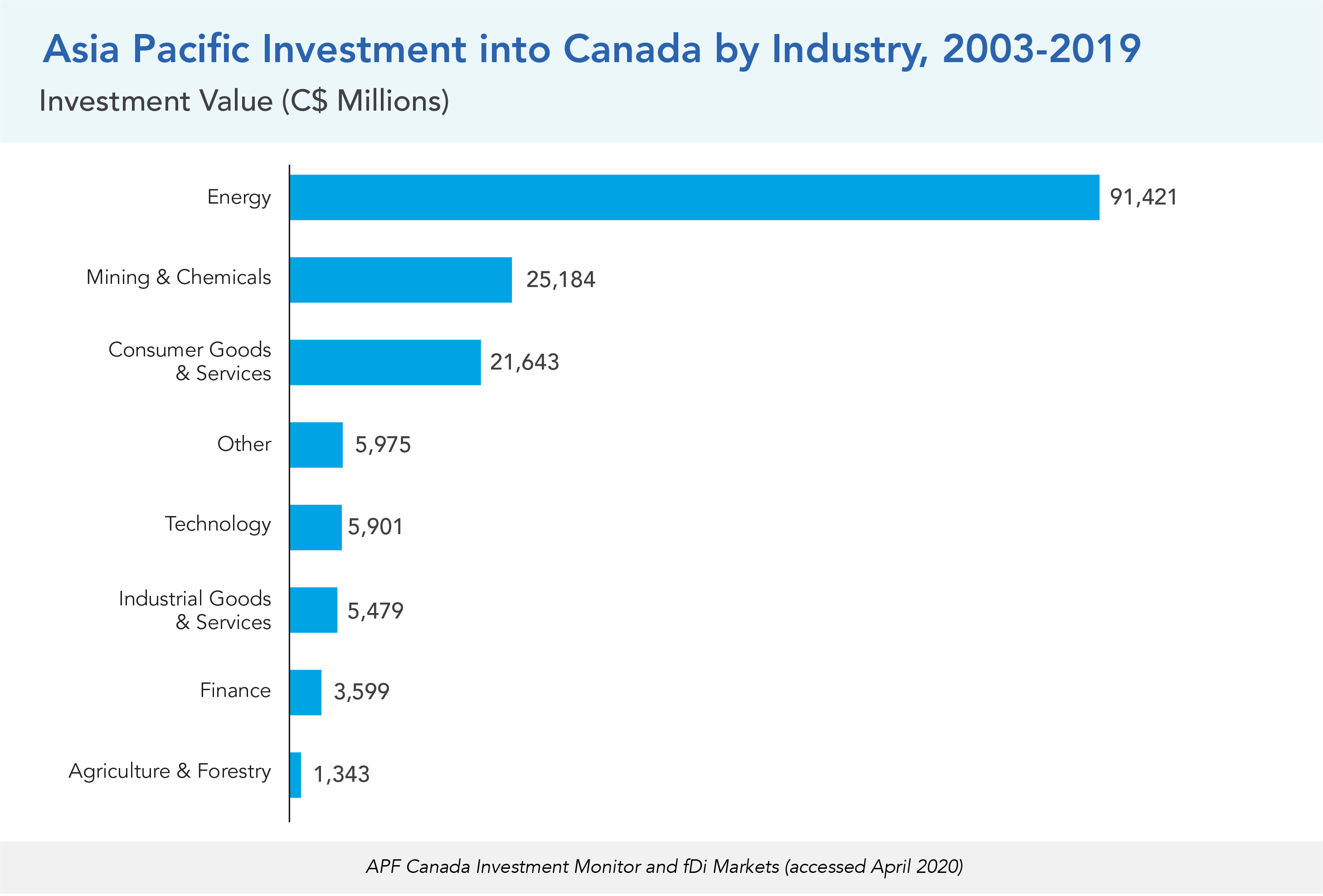

ASIA PACIFIC INVESTMENT IN CANADA’S SECTORS: RESOURCES, TECHNOLOGIES, AND THE REST

Investments from the Asia Pacific into Canada are still primarily in natural resources, which comprises the energy, mining, and agriculture industries. In 2019, half of all inbound investments were in the mining and chemicals industry. This includes the largest deal made in 2019: the C$1.5B acquisition of a 17.6 percent stake in Vancouver-based First Quantum Minerals by Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) Jiangxi Copper, through its purchase of PIM Cupric Holdings. This investment is closely followed by the C$1.3B acquisition of Continental Gold by another Chinese SOE, Zijin Mining. Zijin Mining’s acquisition of Toronto-based Continental Gold is its second in Canada, following the company’s 2018 acquisition of Nevsun Resources for C$1.9B. In contrast, Jiangxi Copper’s acquisition of a stake in First Quantum Metals is its first deal in Canada.

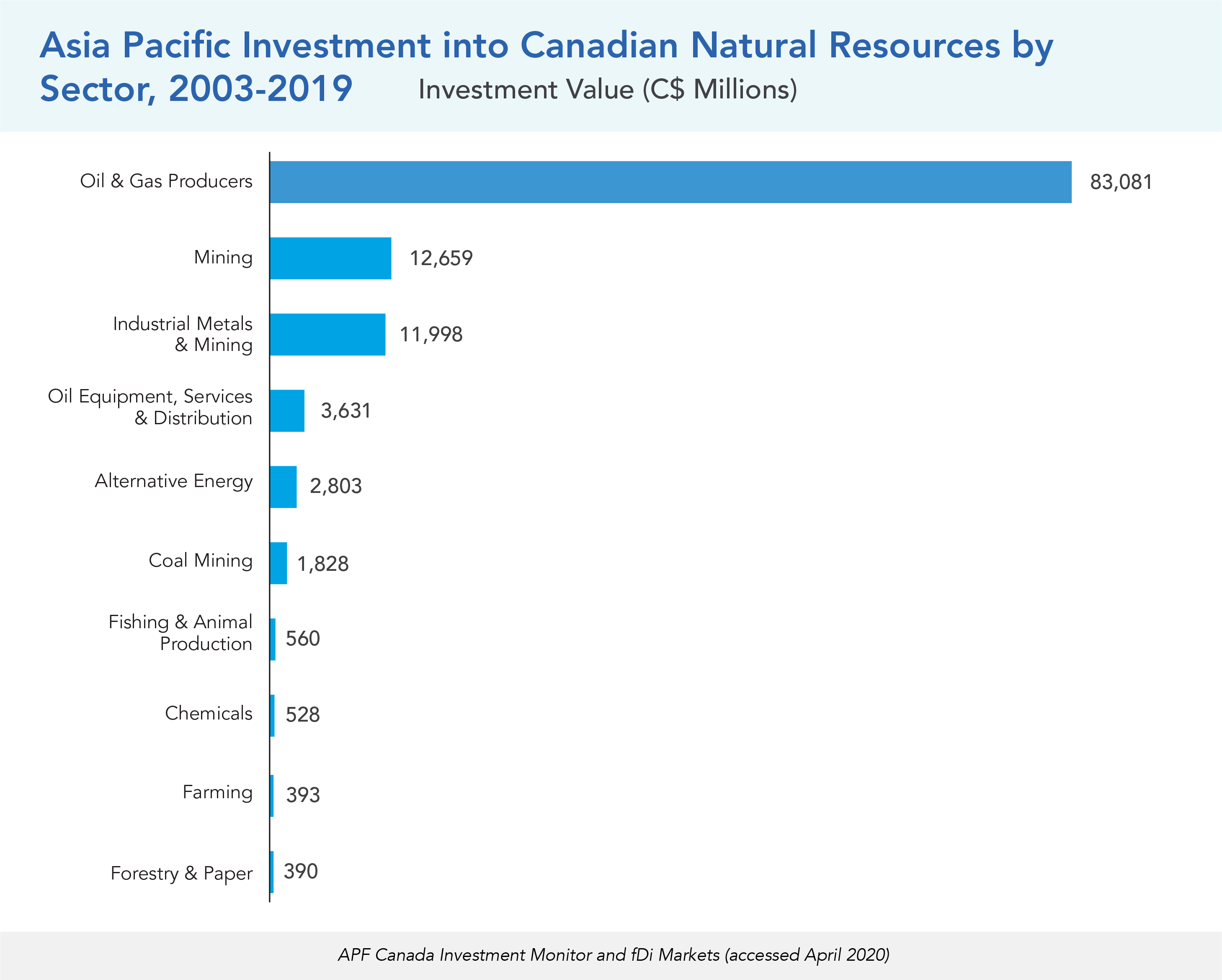

Another noteworthy deal in the mining industry is the acquisition of Halifax-based Atlantic Gold Corporation and Atlantic Mining NS Corp for C$723M by Australian company St. Barbara Ltd. This acquisition is St. Barbara’s first Canadian mine, adding to its existing assets in Western Australia, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. Considering other investments in natural resources, one notable deal in 2019 occurred in the agriculture industry. Manitoba-based pork producer and supplier La Broquerie was acquired for C$498 by Thailand-based Charoen Pokphand Foods PCL through its Canadian subsidy.

As for the main sectors of inbound investment in Canadian natural resources, in 2019 the mining sector received the highest dollar amount, made up of the deals mentioned above. Overall since 2003, the top sector continues to be oil and gas production, totalling C$83.1B. From 2016 to 2019, this sector again tops inbound investment at C$30.4B, remaining largely consistent with the 2012 to 2015 period, when the sector received C$30.6B. For the mining sector, there was a substantial increase in investments, from C$1.9B from 2012 to 2015 to C$7.3B during the 2016 to 2019 period. This increase is largely due to acquisition deals in 2018 and 2019.

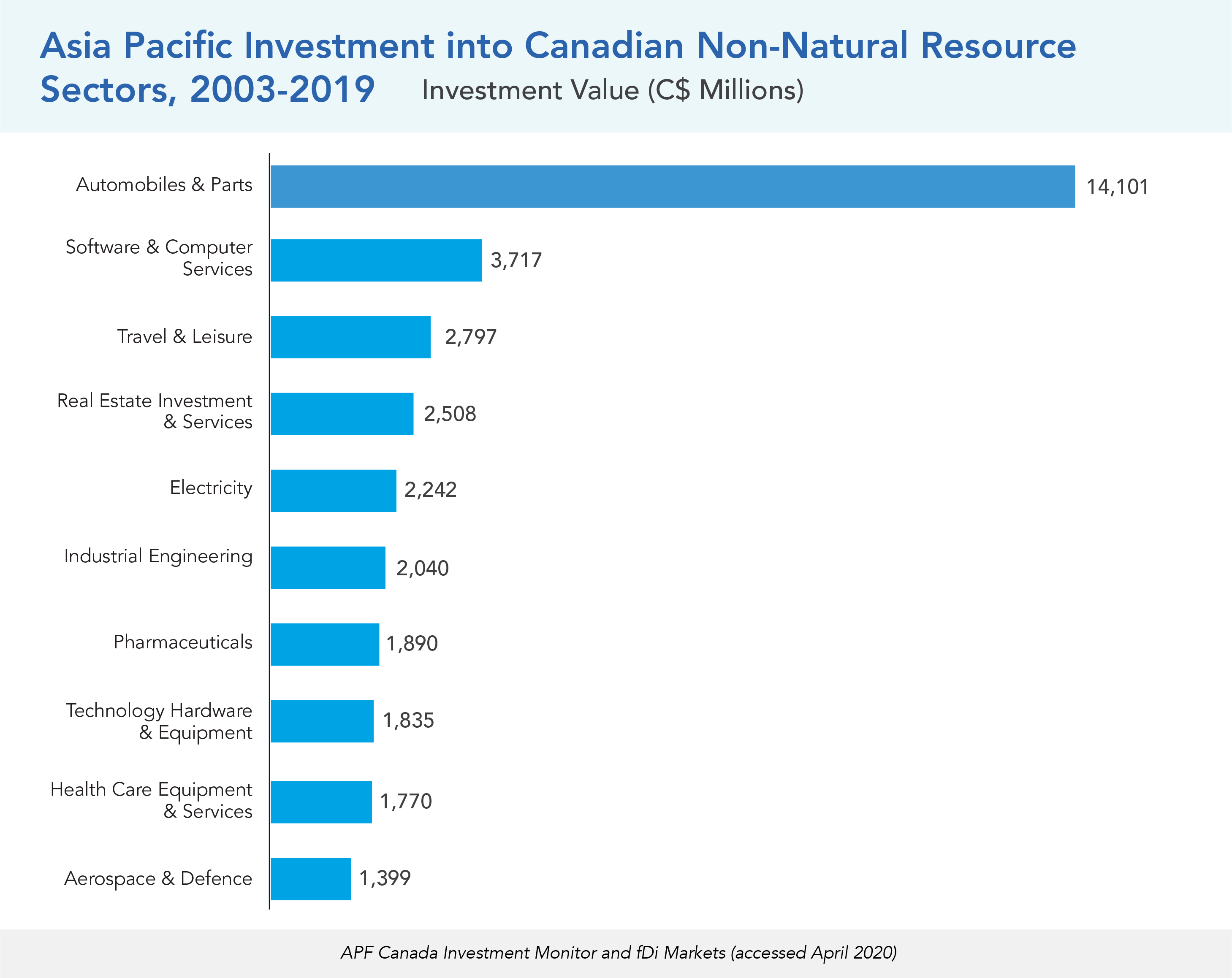

While natural resources are by far the largest area of inbound investment from the Asia Pacific, there is also substantial investment being made in other sectors. Among these, automobiles and parts is the largest, with C$14.1B invested since 2003. This is followed by the software and computer services sector at C$3.7B and the travel and leisure sector at C$2.8B. Investments in these sectors mainly come from Japan and China, with the exception of travel and leisure, which is dominated by Hong Kong-based investors.

One growing area of inbound investment is the technology industry. The number of deals in technology has steadily been rising, from 13 during the 2008 to 2011 period, to 67 during the 2016 to 2019 period. Investment amounts have also risen, from C$396M in 2008 to 2011, to C$1.7B in 2016 to 2019. From 2016 to 2019, 32 percent of investment in Canadian tech was located in Toronto, while Montreal and Vancouver received 13 percent and 7 percent shares, respectively. In 2019, the largest deal was China-based Huawei Technologies’ C$452M expansion of its operations in Canada. Another notable deal in 2019 was Indian multinational tech company HCL Technologies’ C$213M investment in a new office in Moncton, New Brunswick.

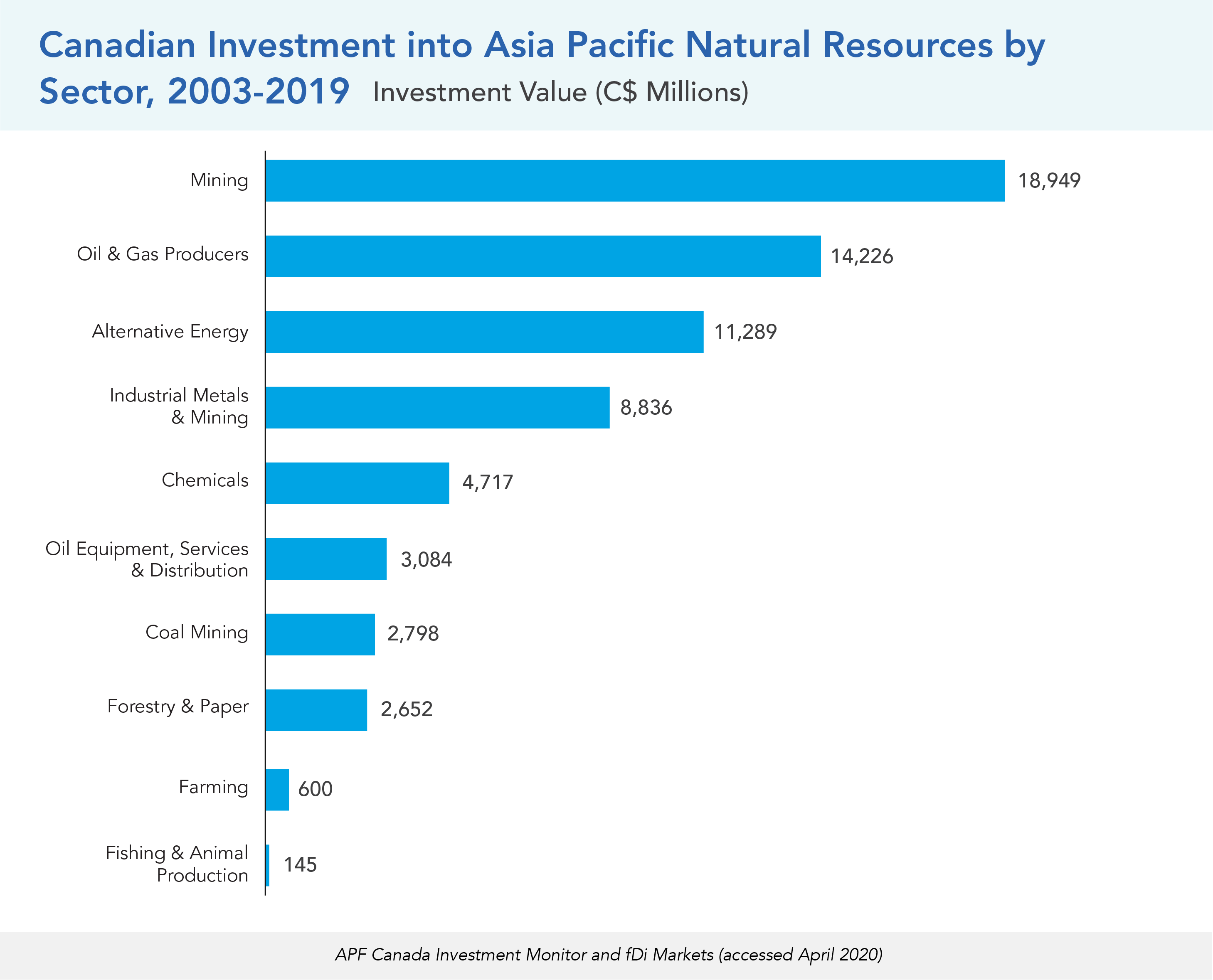

Canada’s natural resource industries (energy, mining and chemicals, and agriculture and forestry) have been significant drivers of investment from the Asia Pacific and accounted for 74 percent (C$120B) of the total value of investment from 2003 to 2019. Of total investments in the industry, the energy sector had a majority share at 75.6 percent (C$91.4B), while the mining and chemical sector and the agriculture and forestry sector account for 23.3 percent (C$28B) and 1.1 percent (C$1B), respectively.

Investment inflows from the Asia Pacific experienced a peak of 40 percent (C$48.2B) of total investment in the industry during the 2011 to 2014 period, when Canada had a large-scale C$16.7B investment deal when Nexen was purchased by the China National Offshore Oil Corporation in 2013. However, the inward flows of investment in the industry have been decreasing since 2013 because of declining commodity prices and a lack of big deals. Investments from the Asia Pacific into Canada’s natural resource industry continue to persist, however. For instance, in the energy sector, LNG Canada, a joint venture comprised of multiple companies from Canada and Asia, invested C$24.5B into Canada’s oil and gas producers in 2018.

Within Canada’s natural resources industries, investment in the agriculture and forestry sector was not as big as it was in other sectors. One of the largest deals in the sector was a purchase of the assets of the Terrace Bay Pulp Mill in Ontario by India-based Aditya Birla Group for C$279M in 2012. Moreover, no investments were recorded between 2016 and 2018 in the sector. However, in 2019, Thailand’s Charoen Pokphand Foods acquiring Manitoba-based HyLife for C$498M was one of the highlights in the sector.

Canada is a global hub for video games. With appealing tax incentives and globally recognized creative talent, Canada has attracted renowned foreign studios, like the French company Ubisoft and American studios Epic Games and Electronic Arts, to settle in cities like Montreal and Vancouver. Beloved game franchises like Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed series and Epic Games’ online game Fortnite are being developed in Canada with homegrown talent. Overall, according to the Entertainment Software Association of Canada, the Canadian video game industry contributed C$4.5B to national GDP in 2019. (Moreover, an estimated two-thirds of Canadians are gamers.) It comes as no surprise that studios based in the Asia Pacific are also interested in benefitting from Canada’s growing video game industry. According to the Investment Monitor, from 2005 to 2019, C$1.3B in investment arrived from the region into Montreal, Vancouver, Burnaby, Toronto, and Saskatoon.

Montreal, in particular, has become one of the top cities in the world for video game development. Called by some the “Hollywood of video games,” Montreal is the fifth most popular city for game development, after Tokyo, London, San Francisco, and Austin. This is largely thanks to Quebec’s multimedia tax credit, which subsidizes up to 37.5 percent of labour costs for eligible companies that develop digital products. One notable studio that has chosen to put down roots in Montreal is Square Enix, a Japanese game developer globally renowned for its Final Fantasy and Kingdom Hearts game franchises. In 2007, Square Enix invested C$226M to establish its first studio in Montreal, named Eidos-Montréal. It has since invested in expanding the studio in 2011 and 2019. Eidos-Montréal is best known for producing games in the Tomb Raider and Deus Ex franchises. Most recently, in 2019, one of China’s top online game providers, NetEase, invested C$130M into a new studio focused on research and design. NetEase is known for publishing games like Crusaders of Light and UNO! the mobile game.

However, not all inbound investments have been successful. In 2005, Japanese developer Koei Tecmo invested C$380M to establish a Canadian subsidiary and studio in Toronto. The studio, responsible for games like Fatal Inertia and Samurai Cats, eventually closed in 2013. In 2014, Japanese company Gumi invested C$176M in its first Canadian studio in Burnaby. Gumi is well-known in Japan for the mobile role-playing game Brave Frontier. However, after 18 months and no titles released, Gumi closed its doors in 2016, along with its other studios in Sweden, Germany, the United States, and Hong Kong. There are several reasons for each closure. For Koei, observers attribute its closing to unpopular titles as well as competition from Ubisoft, once the French studio settled in Toronto in 2010. For Gumi, its closures are seen as a consequence of rapid hyper-expansion.

Overall, while some big players like Square Enix have found success in Canada, others like Gumi have not. Reasons for closures vary across studios, from releasing unpopular titles, losing provincial tax incentives, merging with a bigger studio, and competition. Considering these barriers, provincial governments must go beyond just attracting studios to settle in their cities, and work toward sustaining their long-term presence.[17]

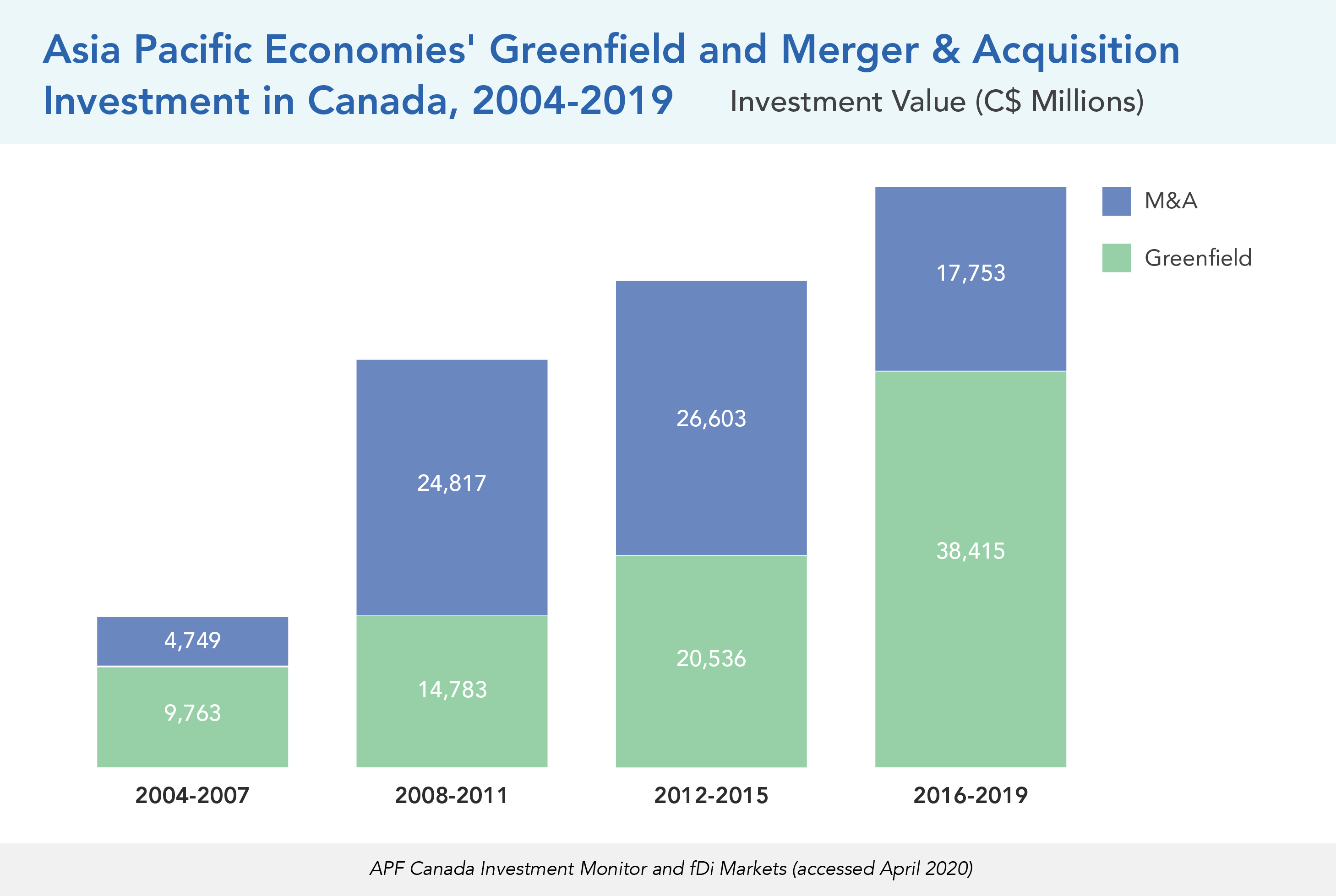

INVESTMENT TYPES: GREENFIELD INVESTMENT VS. M&A

Overall, Asia Pacific investments into Canada are greenfield-oriented. In last 16 years, greenfield deals account for 62 percent of all inbound investment transactions from the Asia Pacific, while mergers and acquisitions (M&A) only make up 38 percent. However, given that M&A transactions on average carry a higher dollar value per transaction, they make up a larger proportion of the inbound investment value compared to deal numbers. Over the last 16 years, M&A makes up 47 percent of the value of inbound investments from the Asia Pacific, while greenfield investments account for 53 percent.

In the most recent four-year period, greenfield investments remained the dominant mode of entry for Asia Pacific companies. From 2016 to 2019, greenfield investments accounted for 247 of the 428 deals (58 percent) and C$38B of the C$56B inbound Asia Pacific FDI (68 percent). Compared to the period from 2012 to 2015, greenfield investments have increased by C$18B in dollar value and 89 in deal count.

While inbound Asia Pacific M&A investments continued to grow in number of deals, the dollar value of this mode of entry slightly dropped over the last eight years. From 2016 to 2019, Asia Pacific companies invested C$18B into Canada through 181 M&A deals. Compared to the previous four-year period (2012-2015), Asia Pacific M&A investments from 2016 to 2019 more than doubled in deal count, but dropped by C$9B in dollar value.

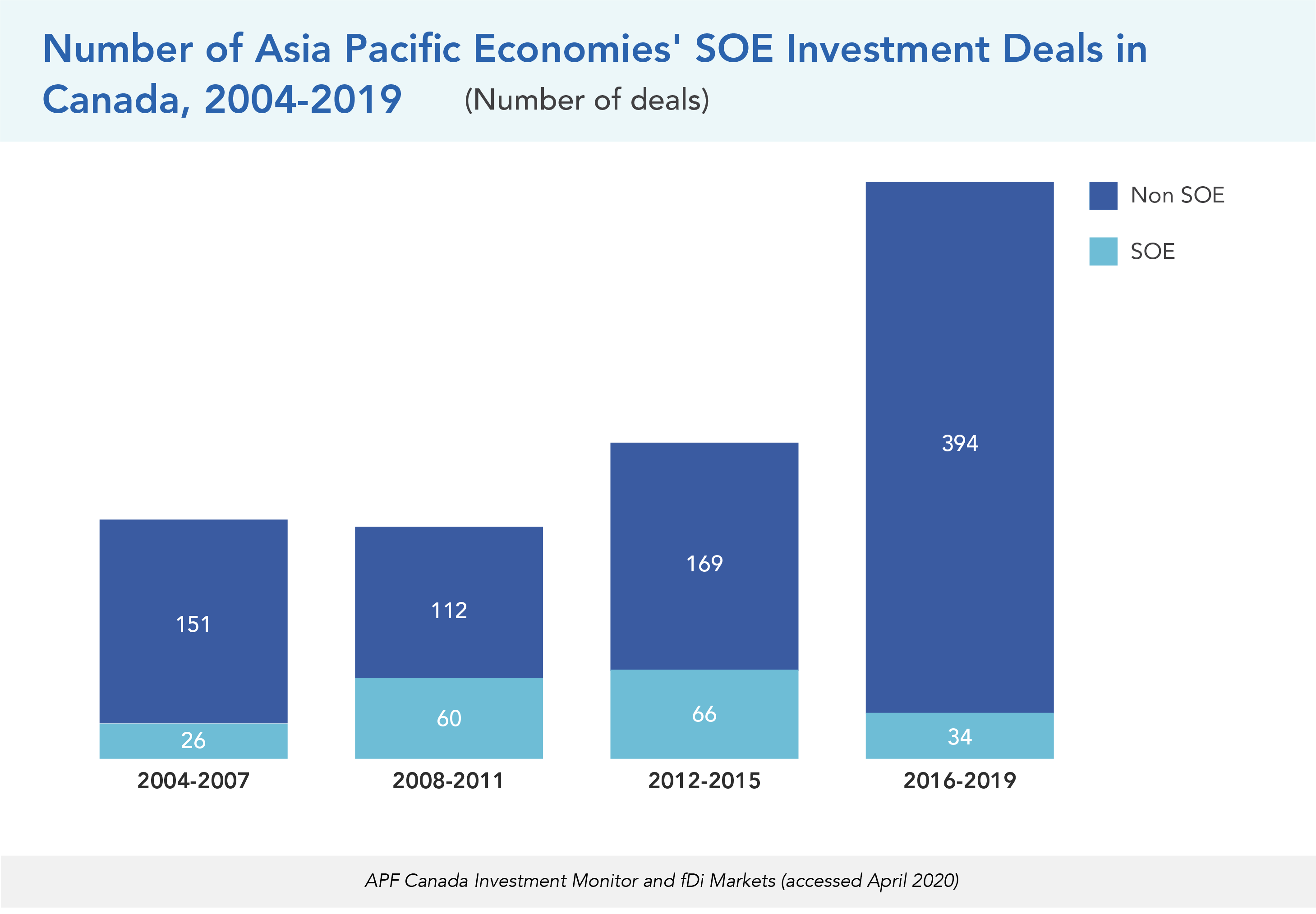

STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES IN CANADA: DESPITE THE PUBLIC ATTENTION, A DECLINING FACTOR

APF Canada’s 2019 National Opinion Poll showed that Canadians are more skeptical of inbound Asia Pacific investments from SOEs in the high-tech sector. Compared to investments from a privately owned company, investments from SOEs are five percentage points more likely to be disapproved of by Canadians.[18]

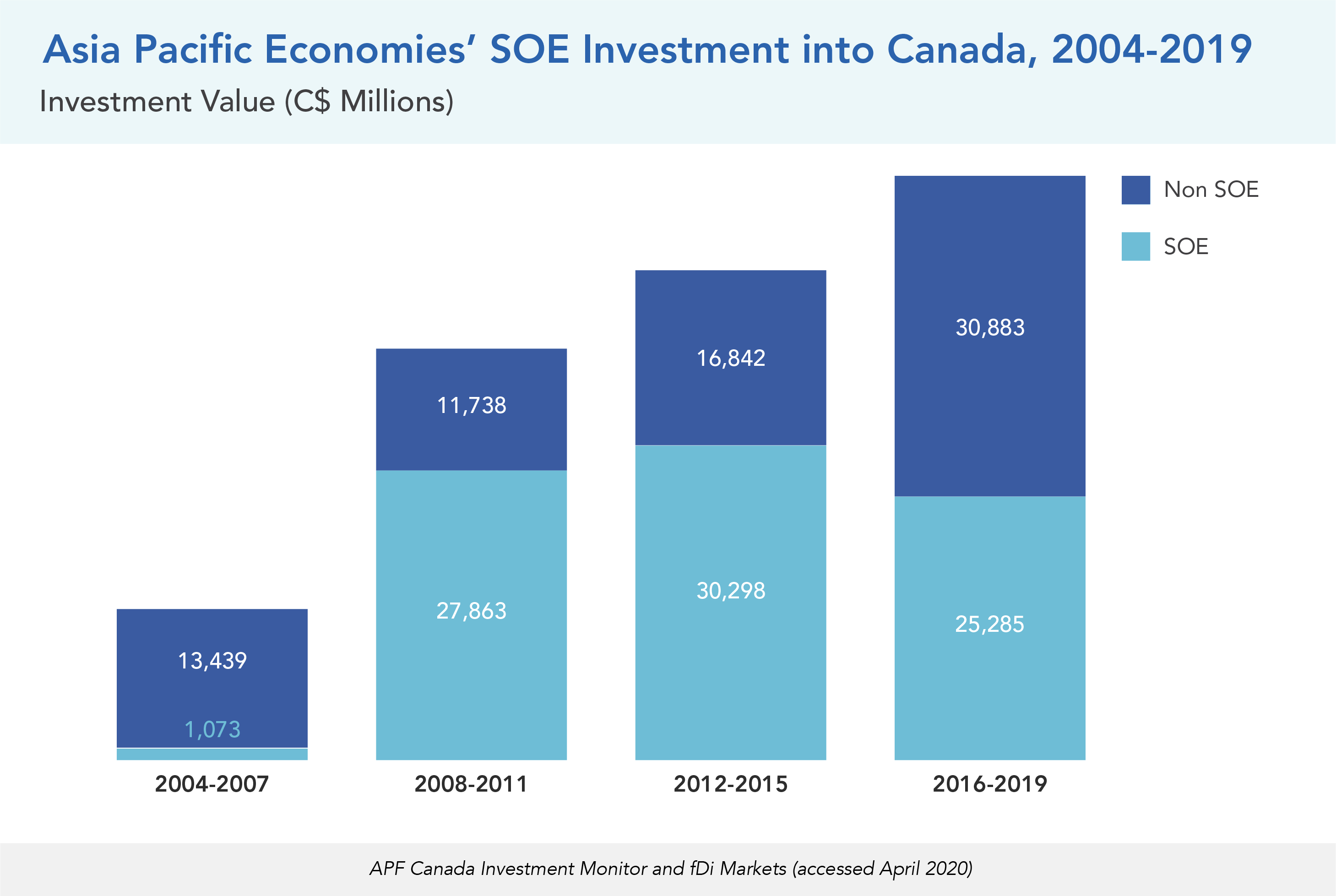

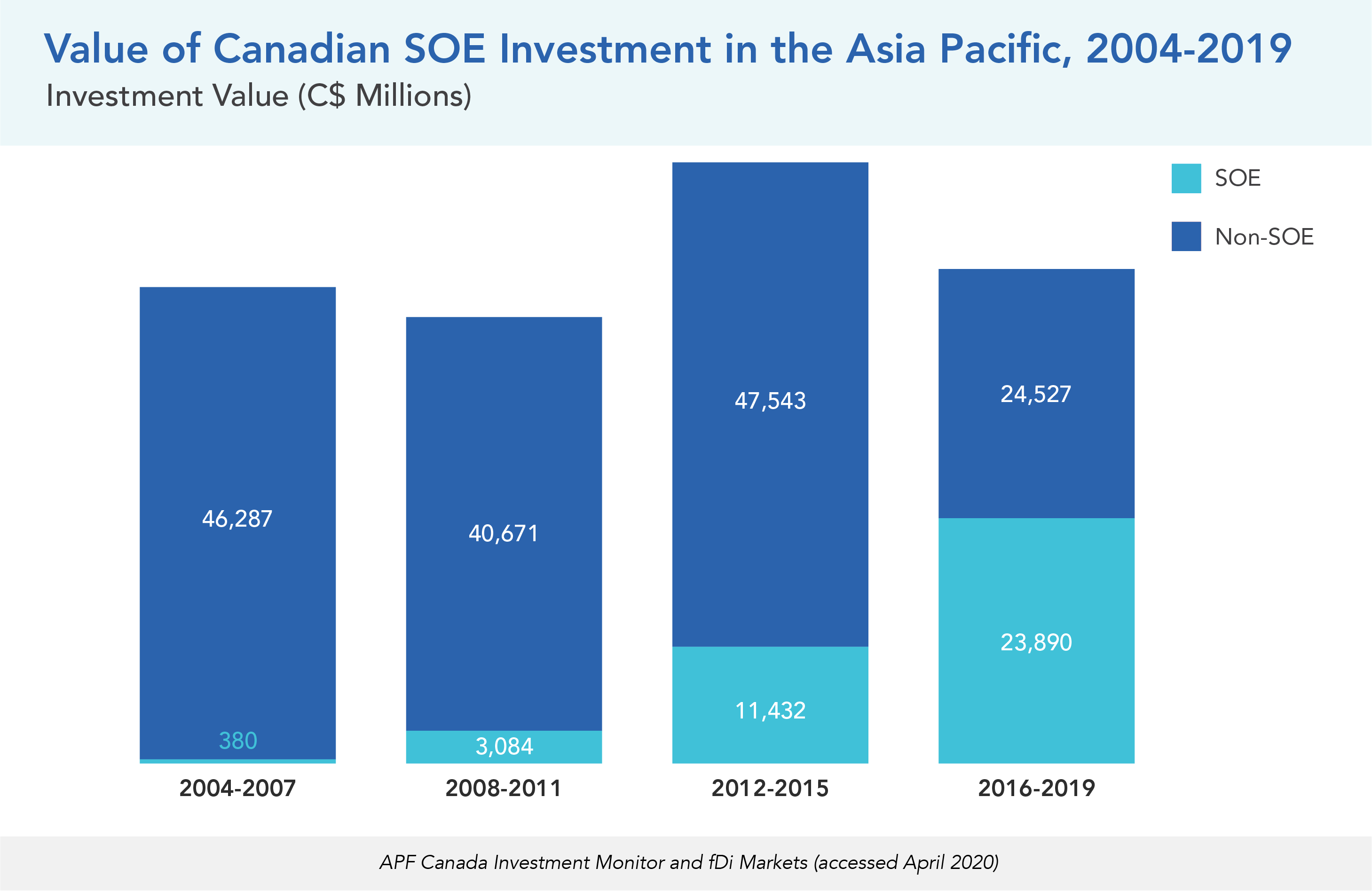

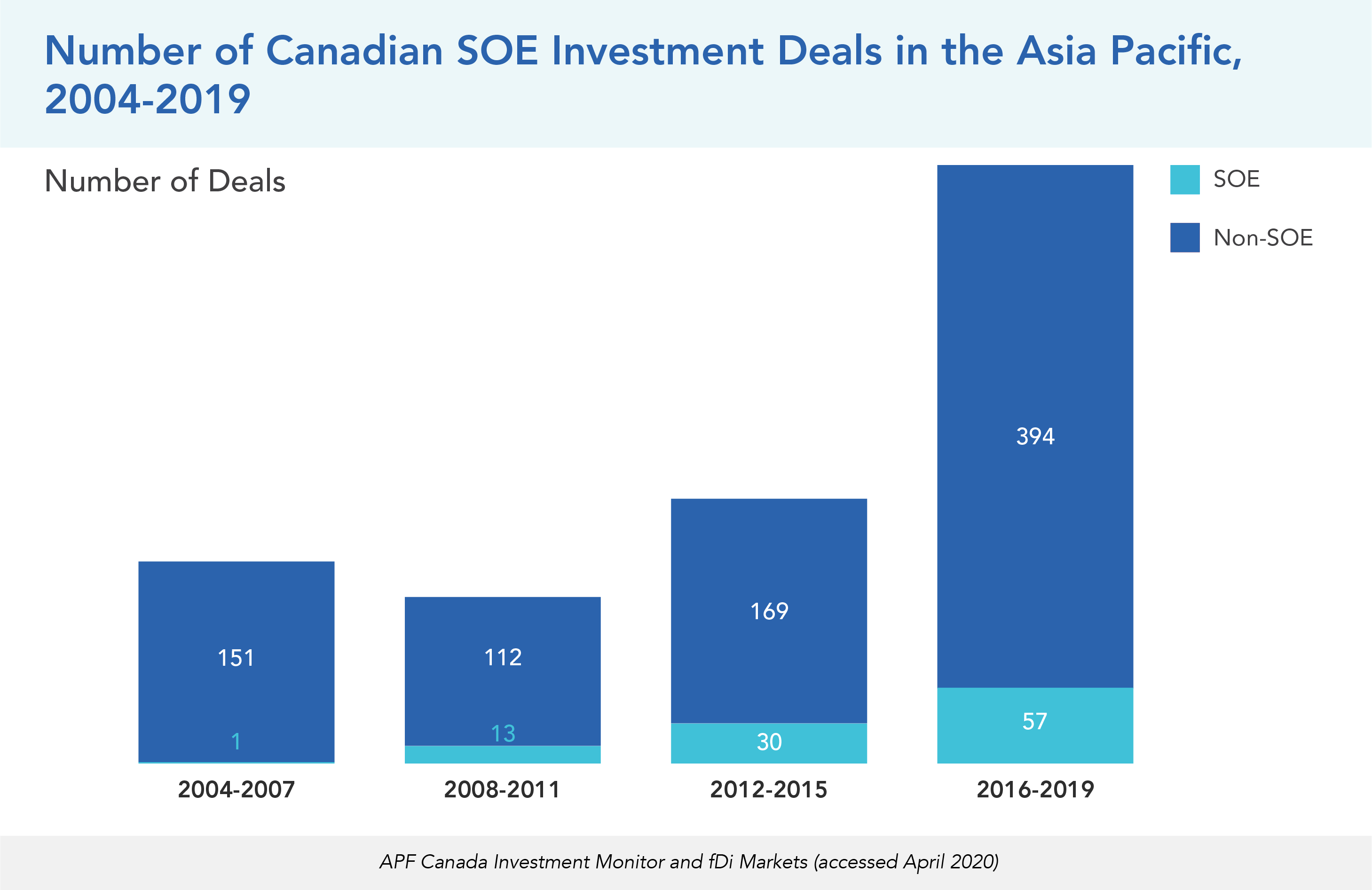

While Asia Pacific investments by SOEs into Canada had steadily grown from 2004 to 2015, activities subsided in the most recent four-year period. From 2016 to 2019, there were 34 inbound investment deals by Asia Pacific SOEs, and this number was less than half that of the 2012 to 2015 period. In the same period, China remains the most active source of SOE investments, accounting for 18 of the total 34 SOE deals.

The most recent four years have also seen a substantial increase of non-SOE investment in comparison to the 2012 to 2015 period. Between 2016 and 2019, non-SOE investment was at a 16-year high with 394 transactions, more than doubling the deal count from the previous four-year period. China, Japan, and India are the top sources of Asia Pacific non-SOE investment, with 95, 87, and 62 inbound deals, respectively.

A similar picture can be painted when looking at Asia Pacific SOE investment in dollar value. As Figure 15 shows, investments into Canada from Asia Pacific SOEs peaked in the 2012 to 2015 period with C$30B and declined to C$25B in the 2016 to 2019 period. As Asia Pacific SOE investment into Canada has dropped, inbound non-SOE investment from the region has skyrocketed. Canada saw C$31B of investment by Asia Pacific non-SOEs in the latest four-year period, an 83 percent increase from the 2012 to 2015 period.

During the 2008 financial crisis, Canadian FDI inflows from Asia Pacific economies remained strong as a new wave of investments led by China’s “Go Global” policy in Canada started. In 2008, Canada received C$5.2B in investment from the region, an 85 percent increase from the previous year’s total of C$2.8B. Furthermore, in 2009, Canadian inbound investment from the Asia Pacific reached C$7.3B, a 42 percent increase from 2008. During the economic crisis, three economies – China, Japan, and Australia – dominated Canadian inbound investment. The biggest source economy between 2008 and 2009 was China with C$5.8B, accounting for 46 percent of the total C$12B of investment from the Asia Pacific. Meanwhile Japan invested C$4.6B, making up 37 percent of the total amount. Lastly, Australia invested C$1.7B, accounting for 14 percent of the total investment inflow from the region during this period.

The biggest deal made in 2008 was a C$1.2B investment by the Japanese automaker Toyota Group in the Canadian automobiles and parts sector, for a new auto assembly plant in Ontario. In 2009, the biggest deal was a C$2.3B investment by Chinese SOE China National Petroleum Corp. in the Canadian mining and oil and gas sector, when it acquired 60 percent of the shares of Calgary-based Athabasca Oil Sands Corp.

On the other hand, outbound Canadian investment into the Asia Pacific amounted to C$17B in 2008, a 35 percent increase from the previous year’s total of C$12.6B. However, in 2009, Canadian outward investment dropped by 43 percent to C$9.7B. Between 2008 and 2009, China saw the lion’s share of Canadian investment, receiving C$8.6B and accounting for 32 percent of the total C$26.7B of outward investment flows to the region. In second place, Vietnam received C$5.6B, accounting for 21 percent of the total outward investment, while in third place Australia received C$4.2B, accounting for 16 percent. India also received C$3B of investment from Canada (11 percent), making it the fourth-largest recipient among the Asia Pacific economies during the economic crisis.

In 2008, the biggest outbound Canadian investment to the Asia Pacific was made by Toronto-based Asian Coast Development Ltd. with a C$5.1B investment in the Vietnamese travel and leisure sector to build a casino and beach resort. In 2009, the biggest deal was made by Toronto-based Brookfield Asset Management with a C$1.4B investment in Sydney-based Babcock & Brown Infrastructure to acquire a 40 percent stake of the firm.

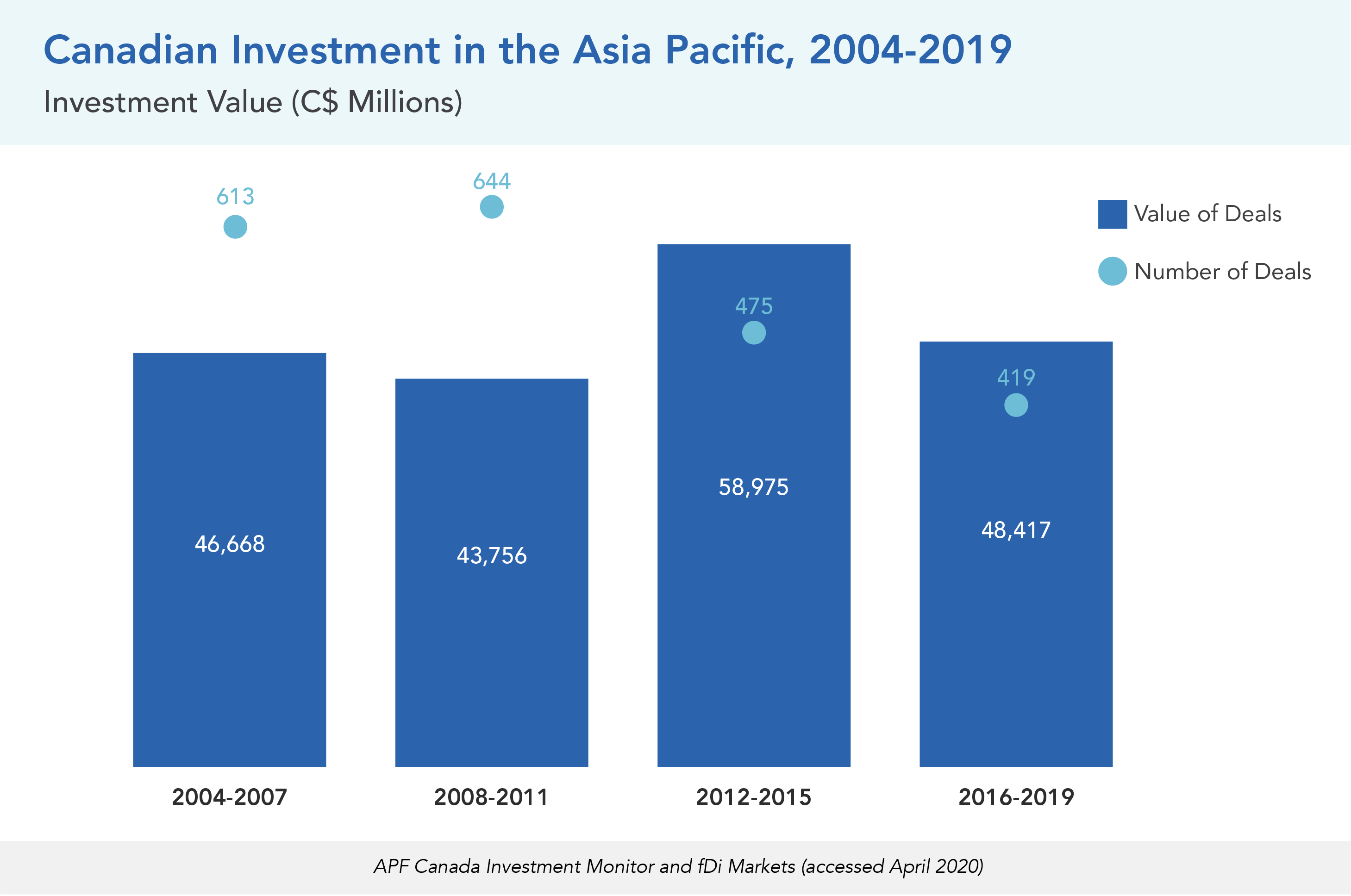

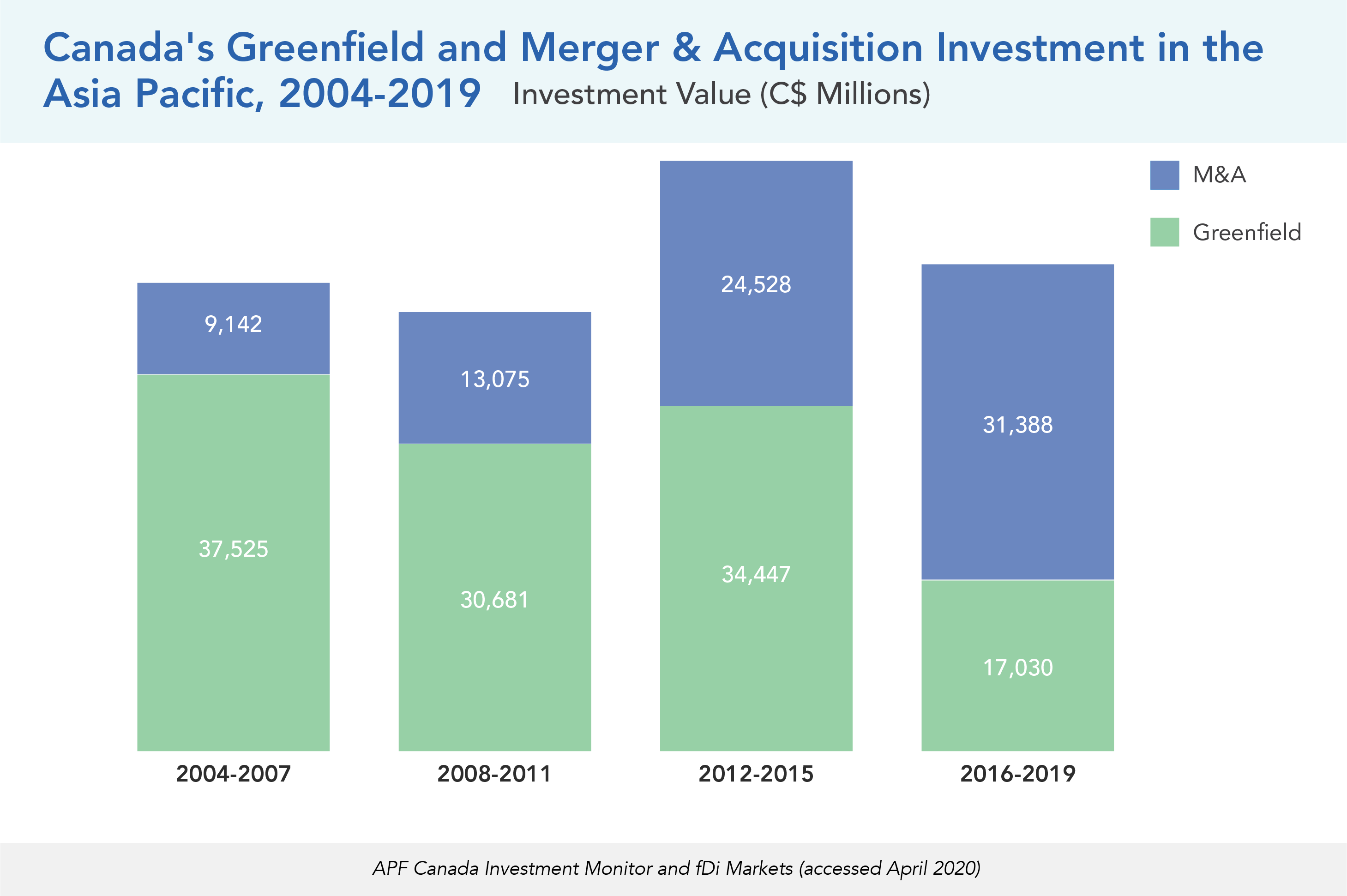

OUTBOUND TRENDS AND PARTNERS: CANADA CONDUCTING FEWER DEALS, WITH FEWER DOLLARS

Canada has invested C$198B in the Asia Pacific economies over the last 16 years through 2,151 transactions. It reached its peak in the 2012 to 2015 period with C$59B. Outbound Canadian investment to the Asia Pacific has since seen a slight drop in the most recent four years. From 2016 to 2019, Canada invested C$48B into the Asia Pacific region. While the investment value in this period was C$10.6B lower than the previous four-year period (2012- 2015), it remains slightly above the two four-year periods before 2011.

In 2019 specifically, Canadian outbound FDI to the Asia Pacific was valued at C$7.2B, a significant drop from the C$18B in 2018. Deal counts also dropped and reached the lowest since 2003 with only 75 outbound FDI deals made that year. The trend in the deal counts in the last 16 years suggests that Canadian companies’ investment interest in the Asia Pacific has declined since 2012. In particular, in the latest four years there has only been 419 outbound investment deals from Canada to the Asia Pacific. This deal count is 12 percent less than the 2012 to 2015 period, which had 475 deals.

From 2003 to 2019, Australia, China, and India were the top destinations for outbound Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific. In this period, the Investment Monitor captured C$66B, C$44B, and C$27B of outbound Canadian investments into Australia, China, and India, respectively. The three economies account for 73 percent of outbound investment into the Asia Pacific region in this period.

India, in particular, has seen a surge in Canadian investment interests. In 2019, the country saw close to C$2B of Canadian investment over 16 deals, making India the second-largest recipient of Canadian outbound FDI that year. In the most recent four-year period, India received more than C$9.4B of investment from Canada, C$1.7B more than the amount of Canadian investment into China. Compared to the 2012 to 2015 period, Canadian outbound investment into India in the most recent four years has jumped by C$5.7B, more than a 150 percent increase. The increased Canadian investment interest in India is also confirmed by deal counts, as the number of outbound investment deals to India increased from 51 transactions in the previous four-year period to 72 from 2016 to 2019.

The Toronto-based Brookfield Asset Management Inc. has become one of the most active Canadian players in the Indian market. In the last four years, the company has invested more than C$2B in the country with a focus on the country’s real estate investment and services and technology hardware and equipment sectors. One of its biggest investments came in 2016 when Brookfield acquired retail and offices spaces from Hiranandani Group for C$1B. Brookfield made another significant investment in India 2019, as the company made a C$493M acquisition in the Mumbai-based telecom tower company Reliance Industrial Investment and Holdings limited. In its press release, the CEO of Brookfield Infrastructure explained the move, saying that “this is a unique opportunity to invest in a large-scale, high-quality telecom business and participate in India’s high-growth data industry.”[19]

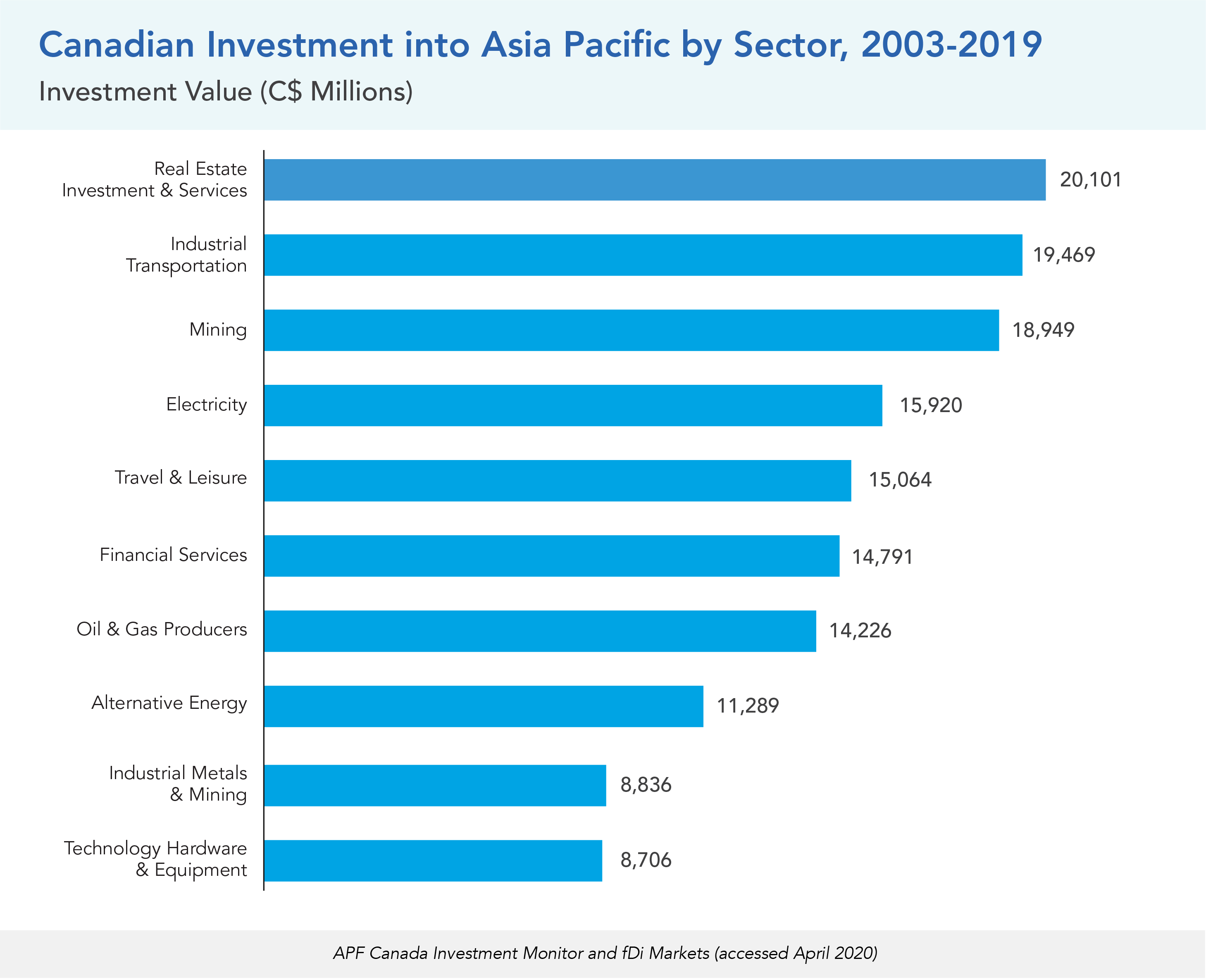

CANADA INVESTING IN A VARIETY OF SECTORS

The top sectors for Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific continue to be industrial transportation, real estate investment and services, and mining. Real estate investment and services has been the top sector of outbound investment since 2003. The sector is worth C$20.1B and makes up almost 10 percent of all Canadian outbound investments to the region. It is followed by industrial transportation at C$19.5B and mining at C$18.9B, making up 9 percent each of Canada’s total outbound investment. The mining sector notably fell to third place from its previous ranking as the top sector in the last annual report.

For 2019, 17 percent of Canadian investment went toward the automobiles and parts sector, with a dollar value of C$1.3B. The majority of these deals involved the establishment of new manufacturing plants for electric cars in China. The largest deal is from electric car manufacturer Electra Meccanica Vehicle Corp., which invested C$798M into a new production facility in Chongqing, China. The second biggest deal is Magna International’s joint venture with China-based BAIC Group to build an electric car factory for C$398M in Zhenjiang, China.

Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific’s energy industry peaked in the 2012 to 2015 period, at C$12.4B, more than doubling its previous value of C$5.3B during the 2008 to 2011 period. However, for 2016 to 2019, this value fell to just C$673M. The reason for this decrease is several large deals from 2012 to 2015. The biggest of these took place in 2015, made by SkyPower, Baytex Energy Corp., and Fulcrum Environmental Solutions Inc. SkyPower is a Toronto-based solar power producing company that invested C$6.1B in Bangladesh’s solar power sector. Baytex Energy Corp. is a Calgary-based oil and gas company that acquired Australia-based Aurora Oil & Gas Limited for C$2.9B. Fulcrum Environmental Solutions Inc. is an Edmonton-based clean technology company that invested C$1.2B worth of proprietary technology into China-based DGF Shandong Industries Corporation’s new clean-coal thermal steam power facility.

On the other hand, Canadian investment in the region’s mining and chemicals industry has significantly decreased. The industry experienced a 73 percent drop in investment since the 2008 to 2011 period, from C$6B during this time to just C$1.6B during the current period (2016-2019). However, 2019 saw several notable deals for the industry. The largest deal is Toronto-based global agribusiness Nutrien’s C$623M acquisition of Australian agricultural merchandiser Ruralco. This is followed by two Toronto-based mining companies’ expansions of operations in Australia, namely Kirkland Lake Gold’s C$361M expansion of its Fosterville mine, and RNC Mineral’s C$361M expansion of its Kambalda mine.

Canada is one of the leading countries in clean technology in the world. The country supplies 17.3 percent of its energy from renewable sources, whereas other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries only produce 10.2 percent, on average. Moreover, Canada was recorded as the second-largest producer of hydroelectricity, providing 60 percent of the country’s electricity generation in 2016. The country has developed not only hydroelectricity intensively but also biomass, wind power, solar power, and liquid biofuels. With such high potential and capacity, Canadian businesses have invested in cleantech markets all over the world, and APF Canada monitors these outflows and investment trends in the Asia Pacific using the modified Industrial Classification Benchmark (Modified ICB) as well as the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

From 2003 to 2019, Canada invested over C$22.6B in 72 cleantech deals in the Asia Pacific. Top destinations for the outbound investments were China, Bangladesh, Japan, Pakistan, India, and Australia. The Investment Monitor data captured C$6.6B worth of Canadian cleantech investment into Bangladesh (3 deals), C$5.1B worth of investment into China (22 deals), C$3.5B worth of investment into Japan (18 deals), C$2.8B worth of investment into Pakistan (2 deals), C$1.9B worth of investment into India (9 deals), and C$1.4B worth of investment into Australia (8 deals). In the past four years, there was a significant increase in the number of Canadian investment deals in the Asia Pacific cleantech sector. The number of deals made between 2015 and 2019 doubled from 16 deals to 35 deals compared to the preceding period (2011-2014), and the amount of Canadian investment in the Asia Pacific increased from C$4.2B to C$13.7B. In 2015, the biggest deal made in cleantech was from Toronto-based SkyPower Global to Bangladesh’s solar power sector, worth C$6.1B.

Considering outbound cleantech investments from Canada, between 2003 and 2019, 50.2 percent was in alternative electricity, 43.7 percent was in renewable energy equipment, and 6.1 percent was in alternative fuels. While almost 55 percent of the total cleantech investment went through greenfield deals, 44 percent went to M&A deals.

Between 2016 and 2019, the Asia Pacific cleantech industry received 22 investment deals (C$3.7B) from Canada, 14 in alternative electricity (C$3B), 6 in renewable energy equipment (C$0.4B), and 2 in alternative fuels (C$0.2B). Top destinations were Japan (40%), India (26%), Australia (17%), and China (6%).

In the past 17 years, health care-related sectors in Canada have received C$3.7B of Asia Pacific investment. The bulk of the Asia Pacific investment in Canada concentrates in the pharmaceutical and health care equipment and services sector, with C$1.9B and C$1.8B of capital injected, respectively. There has been a dramatic increase in inbound investment from the Asia Pacific in the last eight years. In the latest four-year period, Canada has received C$2.1B of Asia Pacific investments, a C$874M increase from the 2012 to 2015 period. Much of the increase has been driven by a 2017 transaction that saw Cedar Tree Investment, a subsidiary of Chinese SOE Anbang Insurance Group, acquire the Vancouver-based Retirement Concept, a retirement home chain, for C$1B. One notable investment in 2019 was the Japan-based Terumo Medical Corporation, a medical device manufacturer, which expanded into the Canadian market with a C$27M investment to open a new facility in Vaughan, Ontario.

From 2003 to 2019, Canadian outbound FDI to the Asia Pacific in health care-related sectors saw a similar level of investment in dollar terms to the inbound FDI from the region. In this period, Asia Pacific economies saw a total of C$3.8B of Canadian investments in health care-related sectors. Of the C$3.8B in outbound investment, C$1.7B went to the pharmaceutical sector, C$1.1B to biotechnology, and C$945M to health care equipment and services. In the last eight years, Canadian investment in the region has drastically increased, from C$273M in the 2012 to 2015 period to C$1.1B in the most recent four-year period. One of the largest dollar-value transactions in the recent period came in 2018, when Toronto-based NorthWest Healthcare Properties acquired a 10 percent stake in Melbourne-based Healthscope, a private healthcare provider, through a C$402 investment.

CANADIAN FIRMS STILL ENTERING WITH GREENFIELD DEALS

Overall, greenfield remains the preferred method of entry for most Canadian companies when investing in the Asia Pacific region. Over the last 16 years, greenfield investments account for 1,531 of the 2,151 deals (71 percent) in total outbound FDI to the Asia Pacific, while M&A only account for 620 deals in this period. In terms of dollar value, greenfield investments captured 61 percent of the dollar amount of Canadian investments in the region, while M&A deals captured the remaining 39 percent.

However, this pattern has changed in the most recent four years. While greenfield deals still made up majority of the Canadian outbound investment deals in the Asia Pacific, the proportion of greenfield investment deals to total outbound transactions has dropped from 77 percent in the 2012 to 2015 period to 66 percent in the most recent four-year period.

Outbound Canadian M&A investments in the region also overtook greenfield investments in terms of dollar amount in this period. Despite making up only 34 percent of outbound deals, M&A deals accounted for 66 percent of total outbound investment value, with C$31B. The 2016 to 2019 period is the only four-year period in the last 16 years in which outbound M&A investments make up a larger proportion of the outbound FDI than do greenfield investments.

CANADA’S SOES NOW MAKE UP A SIGNIFICANT PORTION OF YEARLY FLOW

While Canadians have been particularly concerned about inbound Asia Pacific SOE investments in the high-tech sector, Canadian SOEs have been increasingly active investors in the Asia Pacific region both in terms of the dollar value of their investments and investment activities in the last 16 years. From the 2012 to 2015 period to the most recent four years, Canadian SOEs’ investment in the region increased from C$11B to C$24B, a 109 percent increase. During the last eight years, the number of SOE outbound investments also increased, from 30 deals in the 2012 to 2015 period to 57 deals from 2016 to 2019.

The CPPIB is one of the most active Canadian SOEs in the region. Of the 57 SOE outbound investments recorded from 2016 to 2019, the CPPIB accounted for 25 deals, with a total investment value close to C$14B. Some of its recent notable investments include a C$1.7B investment in Sydney’s WestConnex toll road project and C$1.9B in a Chinese logistics company in 2018. In 2019, the CPPIB also committed C$296M of investment in the Mumbai-based India Resurgence Fund, a distressed asset buyout platform, through its subsidiary CPPIB Credit Investment Inc.

Another notable SOE investment in 2019 was made by the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ), which acquired C$346M of compulsory convertible debentures from the Mumbai-based Piramal Enterprises Ltd. In its company statement, the CDPQ said that the transaction will include a real estate co-investment platform between its subsidiary Ivanhoé Cambridge and the Mumbai-based company.

More than ever, Canada’s outbound investment relationship is being shaped by the presence of large, state-owned funds. The 2010s saw their activity increase dramatically, as these funds – primarily pensions – nearly tripled their flow of new investments, from C$10.2B in the first half of the decade to C$28.3B in the latter half. But while more than half of the investment value in the 2010 to 2014 period was in Australia’s financial services and real estate sectors, more recent years have seen a diversification of investment targets. Investments in Australia’s industrial transportation and real estate sectors still played a major role in the 2015 to 2019 period, but were supplemented by large flows into Mainland China’s real estate investment and services sector and Hong Kong’s general retail sector. Additional flows of investment, worth hundreds of millions of dollars apiece, went into India’s industrial transportation, electricity, and real estate sectors and into South Korea’s general retail and real estate sectors.

The Toronto-headquartered Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, a Canadian state-owned Crown corporation, leads the pack for all Canadian investors in the Asia Pacific. Last year’s C$296M invested into India’s equity investment sector was a small fraction of the C$26.6B in CPPIB investments recorded by the APF Canada Investment Monitor, C$14.7B of which was invested in just the past four years. These high investments have been driven by the CPPIB’s acquisitions in the Australian financial services and industrial transportation sectors, Mainland China’s real estate and industrial transportation sectors, and Hong Kong’s general retail sector.

Another of Canada’s largest, state-owned pension plans entered the Indian market last year, with the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS) investing C$160M into India’s financial services sector. OMERS’s C$6.1B invested into the region has been mainly focused on Australia’s real estate investment and services sector. Likewise, state-owned pension and institutional investor CDPQ invested C$346M into Indian non-equity investment instruments last year, bringing the firm’s total to C$4.2B in the region. Aside from non-equity investments in India, the CDPQ’s investments in the region have centred on India’s electricity sector, Mainland China’s real estate investment and services sector, and Australia’s health care equipment and services sector.

Another state-owned Canadian investor to cross the billion-dollar mark is British Columbia Investment Management Corp., a pension and investment manager, with C$1.3B invested in Australia’s industrial transportation sector. Similarly, the Public Sector Pension Board crossed that threshold with its C$1.1B invested in the region, almost entirely in New Zealand’s travel and leisure sector.

Even with the emergence of Canadian state-owned pensions in the region, large private-sector funds continue to invest significant amounts in the Asia Pacific, typified by the C$1.0B invested in 2019 by Brookfield Asset Management Inc. in New Zealand’s software and computer services sector. The Toronto-based asset management company’s C$14.0B invested in the region, C$9.5B of which was invested in just the five most recent years, has been heavily focused on Australia’s industrial transportation and financial services sectors and in India’s real estate investment and services sector.

Similarly, Toronto-based financial institution Manulife Financial has invested C$6.1B in the Asia Pacific region, mainly in Mainland China’s financial services sector, Singapore’s real estate investment and services sector, and Hong Kong’s life insurance sector.

[16] Newswire. 2019. Jiangxi Copper Acquires FQM Shares from Pangaea Investment Management. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/jiangxi-copper-acquires-fqm-shares-from-pangaea-investment-management-823519821.html

[17] Entertainment Software Association of Canada. 2018. Canada – A Nation of Gamers. http://theesa.ca/2018/10/29/essentialfacts2018/

Entertainment Software Association of Canada. 2019. The Canadian Video Game Industry 2019. http://theesa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/CanadianVideoGameSector2019_EN.pdf

Montréal International. 2020. Montréal, a major player in video games. https://www.montrealinternational.com/en/keysectors/video-games/

O’Mara, Matthew. 2013. Tecmo Koei Canada closing its Toronto studio. Financial Post. https://business.financialpost.com/technology/gaming/tecmo-koei-canada-closing-its-toronto-studio

Suckley, Matt. 2016. Updated: Gumi shutters studios in Canada, Sweden, Germany, Austin and Hong Kong. Pocket Gamer. https://www.pocketgamer.biz/asia/job-news/63055/gumi-closes-vancouver-studio/

[18] Zhu, Yushu. 2019. 2019 National Opinion Poll: Canadian Views on High-Tech Investment from Asia. Vancouver: Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. p. 20.

[19] Brookfield Instructure Partners. 2019. Brookfield Infrastructure Acquires Indian Telecom Towers. https://bip.brookfield.com/press-releases/2019/12-16-2019-112919449

[20] Source: Natural Resources Canada. 2019. Energy Fact Book 2019-2020. https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/energy/pdf/Energy%20Fact%20Book_2019_2020_web-resolution.pdf

[21] Caisse de Dépôt et Placement du Québec. 2019. CDPQ and Piramal Enterprises Strengthen Partnership. https://www.cdpq.com/en/news/pressreleases/cdpq-and-piramal-enterprises-strengthen-partnership

The Provincial Picture

KEY SECTION TAKEAWAYS

- For 2019, Ontario made up the majority of all inbound investment (40 percent), followed by Quebec (18) and BC (3).

- Similarly, for 2019, Ontario made up half of all outbound investment. It is followed by Quebec (23 percent) and BC (14), while Alberta only received one deal this year.

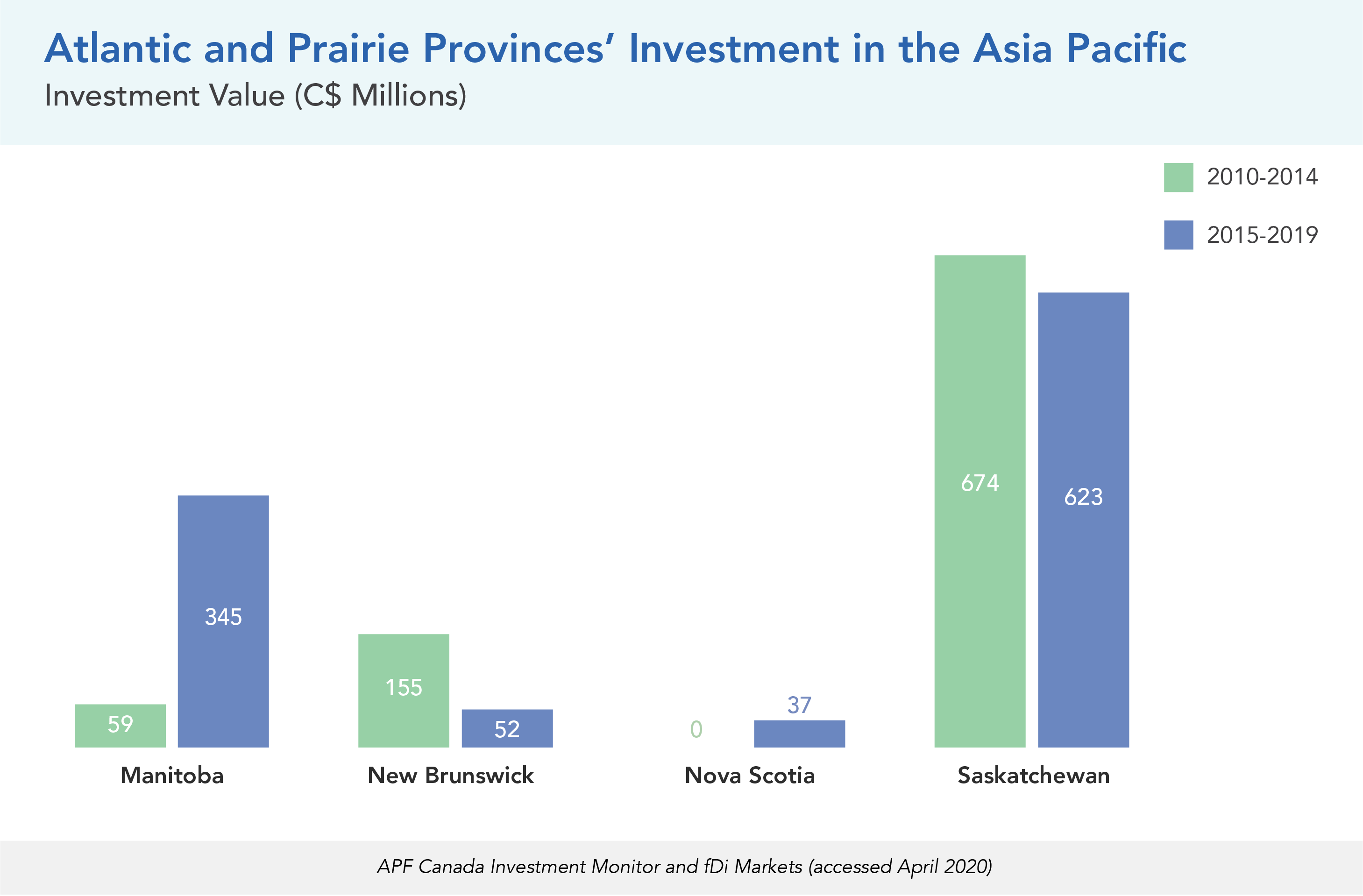

- Comparing the two halves of the decade (2010-2014 and 2015-2019), inbound investment into Alberta dropped dramatically, while inbound investment into BC rose. Meanwhile, Ontario and Quebec both saw slight increases in their inbound flows. The Prairies and Atlantic Canada also saw increased inbound investments in the second half of the decade.

- Considering outbound investment, both Alberta- and BC-sourced flows of investment declined across the decade. On the other hand, Ontario and Quebec both increased their flow of outbound investments throughout the decade.

On the provincial level, FDI flows between Canada and the Asia Pacific are still concentrated in the same four provinces: Alberta, BC, Ontario, and Quebec. Since 2003, 92 percent of all inbound investments have gone to these four provinces, while almost all outbound investments have originated from them. However, while these four retain their status as centres of investment, their relative positions have changed.

FOUR PROVINCES MAKE UP 90 PERCENT OF INBOUND INVESTMENT

Since 2003, Alberta has been the centre of investment from the Asia Pacific, with a third of all inbound investment concentrated in the province. However, in 2019, it received few investments. One example is India-based digital products and services provider Grazitti Interactive’s C$12M investment in a new office in Edmonton. Other investments include Australian engineering company Cardno’s C$7.9M expansion of its Edmonton-based subsidiary, T2 Utility Engineers, and the expansion of Japan-based 7-Eleven across the province, through its subsidiary in Surrey, BC. Overall, Alberta’s inbound investments have dropped significantly, from C$26.4B from 2012 to 2015, to just C$2.8B from 2016 to 2019.

Ontario, in contrast, has seen consistent growth in its inbound investment transaction amounts from 2016 to 2019. In 2019, it received the highest amount of inbound investment and half of all Asia Pacific investments into Canada. This is largely due to several acquisitions by Chinese mining SOEs of Ontario-based mining companies. Jiangxi Copper bought the entire equity interest in PIM Cupric Holdings for C$1.5B, which also gained it a 17.6 percent share in First Quantum Metals. Zijin Mining then acquired the gold mining company Continental Gold for C$1.3B.